This is called stealing the show. To everyone’s surprise, this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics rewarded Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield. Two big names in artificial intelligence (AI) and more particularly neural networks, widely used in modern science. A somewhat controversial choice among local researchers, but which shows an underlying trend: AI is interfering everywhere, including in areas where physics has shined for centuries, such as weather forecasting.

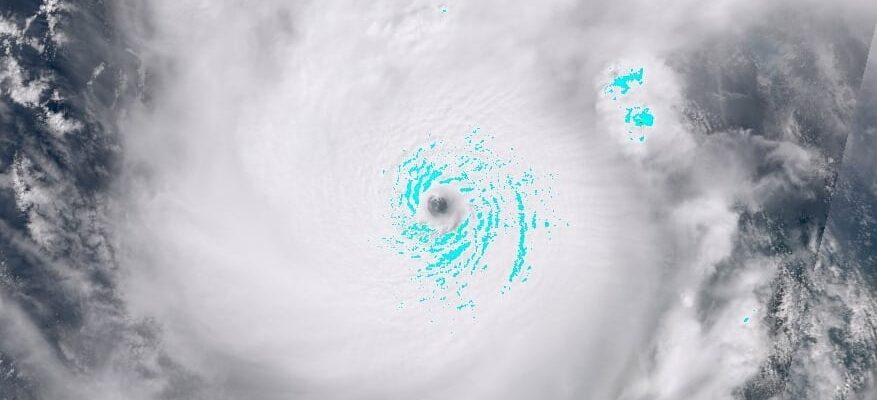

The latest breakthroughs in the field can be attributed to large groups at the forefront of this technology such as Google DeepMind, Nvidia, IBM and Huawei. The first city has just published its new specialized artificial intelligence model at the beginning of December, “GenCast“, trained using the last four decades (through 2018) of weather data. Featured in the journal Nature“GenCast” carries out statistical forecasts on a multitude of variables for up to 15 days, on a spatial resolution of 31 kilometers, showing itself in 97% of cases to be more precise than the best traditional models. This summer, Google DeepMind had already published a model (“GraphCast”) anticipating the trajectory of tropical hurricane Beryl towards Texas, while forecasts instead saw it hitting Mexico head-on. Nearly forty people ultimately died in the southern US state. None in Mexico.

This precision can save lives. It also has obvious economic interests. In case of disaster, first. “Reducing the track error of a typhoon by one kilometer in 24 hours can reduce direct economic losses by about 97 million yuan ($13.54 million) […] a precise forecast is essential to minimize risks”, wrote last January the Chinese media Global Timesabout a locally developed AI model helping to anticipate these devastating events. More broadly, businesses in agriculture, industry, tourism, or administrations aspire to ever greater accuracy to make the right decisions. “Will the wind be strong enough tomorrow to rely on the renewable energy produced by wind farms? What is the probability that the temperature will drop below zero?”, asks for example on his LinkedIn feed Remi Lam, one of the scientists behind “GenCast”.

First revolution

Promising, especially since the love affair between AI and weather is only just beginning. Pierre Gentine, a French researcher specializing in environmental issues and professor at Colombia University in New York, places its beginnings around 2018. At the time, the scientific world was just celebrating the first “revolution” in weather. Advances in computing power – with supercomputers – make it possible to ingest the millions of useful atmospheric data available today. It is therefore possible to model forecasts – always based on physical simulations – faster and more precisely than ever. The Met Office in the UK says its four-day forecasts are now as reliable as their one-day forecasts were 30 years ago. Journalist Andrew Blum compares, in the book The Weather Machine: A Journey Inside the Forecastpublished in 2019, the current weather system is a “marvel treated with banality”. A daily miracle.

No one is thinking of changing their approach. Except Pierre Gentine, and a handful of others, who are turning to the latest approaches to artificial intelligence, advances in machine learning (machine learning) and neural networks which excel at creating new sentences or images from existing ones. In short, anticipate what happens next. At the start, the beginnings are difficult: the data sets are not optimal. “Most of the scientific community was frankly skeptical of the benefits of AI, the implementations of statistical models were still relatively naive and far from matching the performance of existing meteorological models,” relates geoscience researcher Alban Farchi , In an interview published on the website of the École des Ponts et Chaussées, in January 2024. But these first initiatives of machine learning were not carried out by forecasting specialists and, subsequently, international companies poached meteorologists to help them design efficient and appropriate architectures.

The pace of progress has therefore accelerated. “In four years, we went from mediocre predictions to matching the best with AI,” continues Pierre Gentine. In 2022, Nvidia, the king of AI chips (“GPUs”), releases the FourCastNet model, comparing itself to cutting-edge digital weather forecasts from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Today, Google’s advances suggest that AI can push back the wall that everyone faces: forecasting beyond 10 days. “This moment when the system becomes chaotic”, indicates Pierre Gentine. The risk linked to the butterfly effect: a tiny change in conditions somewhere in the world which disrupts the results and renders them obsolete. Not for long?

Fast but unfathomable

This is one of the great hopes of AI. But not the only one. Google’s “GenCast” produces its results with a single “TPU” type chip in just eight minutes. While the ECMWF mobilizes its supercomputer each time, i.e. tens of thousands of processors, for several hours. While training AI-based weather models requires significant resources, using them via a simple desktop computer is much less expensive. An asset to which poor countries, less equipped with infrastructure, should be sensitive. For some, underlines the reference statistics site Our World in Data, the quality of a one-day weather forecast barely equals the more uncertain seven-day weather forecast of rich countries. This would also make it possible to optimize the excellent daily forecasts of States better off in this area. “Instead of 20 simulations, we can carry out 20,000 and more easily identify where the mass of coherent results is located,” indicates Nicolas Baldeck, founder of the Météo-Parapente site, and expert in weather data.

However, limits remain. French researcher Pierre Gentine is associated with a start-up, Tellus AI, which tries to anticipate risks in the medium term, up to several months, such as droughts, heat waves and even floods. A popular business at the moment, as highlighted by a recent L’Express survey. With the aim of prediction over several years, in order to anticipate events occurring once a century, as in Valencia recently. However, AI alone will not be able to solve this puzzle. “This kind of flood happens once every 100 years, so there is no history in the data,” confides Pierre Gentine. Physical simulations remain necessary. Especially since the number or intensity of extreme events could in the future be increased tenfold by global warming.

This explains the still cautious approach of the sector’s leading institutions. “AI remains a black box. We cannot afford to provide information that is calculated by an algorithm whose functioning we do not understand,” reminds L’Express Laure Raynaud, the “Madame AI” of Météo-France “We are rather looking for complementarity with the traditional method.” However, she admits: Météo-France has been shaken up. “We did not necessarily have the GPU processors or data science skills available. This requires redefining certain priorities and objectives.” To continually reorient your research: tech giants release new models several times a year. Forcing a new form of collaboration.

“It’s not Google that decides”

Meteorologists help improve AI models. Tech multinationals share their source codes with these researchers, who use them more and more in their daily lives. Everyone can win. The objectives between the organizations and these multinationals are, in any case, not the same. “Our priority is the safety of property and people,” says Laure Raynaud. “It is not Google that will decide whether a French department will be placed on orange alert.” The best forecast is not only the most accurate, but also the one that is correctly delivered to the inhabitants of a specific area, within the appropriate time frame. A Météo-France or the Met Office in the United Kingdom maintain public confidence at this level.

Big Tech is, moreover, dependent on the traditional system. “We provide the raw material,” comments Florence Rabier, the French meteorologist at the head of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), to L’Express. The specialist refers to satellite observations, planes and radio soundings which have been measuring the composition of the atmosphere for decades, and which are financed by governmental and intergovernmental organizations. These infrastructures continue to multiply. Florence Rabier gives as an example the constellations of third generation satellites which will soon enter service in Europe, opening up the possibility of making forecasts with a resolution of only one kilometer. The success of weather forecasting relies on this: global collaboration in real time, with rules and standards defined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Because, like the Chernobyl cloud, the rain or the wind do not stop at the borders. Google’s “GenCast” would not have seen the light of day without the valuable “ERA5” dataset from ECMWF, with information some dating back to 1940.

Could this change? A trailing sky is settling over the forecasters. “Meteorology has long been a public good, but those days may be numbered,” wrote the journalist and author of Weather Machine Andrew Blum, in the Financial Times. “Recent years have seen a boom in private observation – microsatellites, balloons and the adaptation of cell phone metadata for weather sensing. What this portends is a breakdown in the international weather order which has held since the Second World War,” he warns. Big Tech may one day have the means to shape its own data sets. “It’s not for now,” reassures Florence Rabier, of the ECMWF. While remaining cautious, aware of the extraordinary rise of these companies in many areas beyond the weather. “We will have to continue to do the best possible, so as not to rely on large technological groups.” Over the last ten years, the massive opening of data has also contributed to the birth of myriad weather patches on our smartphones. The free, pre-installed ones from Apple or Google which tell us the probability that it will rain in the hour, before the start of a run. But also “Windy”, “RainToday” or “Météociel”, so popular on application stores, that they are now stealing the show from Météo-France. A bit like AI researchers to physicists.

.