The “Geneva patient” should have died twice. First in the 1990s, when he caught AIDS, a disease then synonymous with certain death, for lack of treatment limiting its multiplication in the body. In 2018, then, when his doctors detected a form of the most aggressive leukemia, with particularly low chances of survival.

Twice, the patient who wished to remain anonymous, got away with it. He is now cured of his blood cancer. And now, for 20 months, HIV has not been found in his body, despite extensive analyses, making him the 6th patient in remission from the infection. A small miracle, something “magnificent”, “magical”, welcomed the person concerned, in a press release.

Unveiled this Thursday, July 20 by the Pasteur and Cochin institutes – two French institutions at the forefront of virus detection techniques – in collaboration with the iciStem consortium and the hospitals of Geneva, this case upsets scientists: unlike the others, the patient from Geneva should not have overcome the disease, which still kills hundreds of thousands of people around the world each year.

So far, the only five cases of remission recorded worldwide, patients from Berlin, London, Dusseldorf, New York and City of Hope, followed the same formula. Suffering from terminal cancer, they all received bone marrow transplants from donors with a genetic mutation called CCR5-Δ32. These extremely rare cells protect against HIV.

A transplant without mutant cells

Ten years after the Berlin remission, the first of its kind, the patient from Geneva, meanwhile, received a classic transplant, for lack of compatible donors. A specificity that overturns medical perspectives: “We discover that there are other mechanisms which make it possible to eliminate the virus than what we know”, rejoices Professor Asier Sáez-Cirión, head of the Viral Reservoirs unit at the Institut Pasteur.

In the immediate future, the discovery does not change anything in the daily lives of patients. “It’s more a result for science, for researchers, than for patients. For the moment, the latter will have to rely on treatments, which, although they are more and more effective and tolerated, do not allow healing”, nuance Hugues Cordel, president of the French Society for the Fight against AIDS, and doctor at the AP-HP.

Still, the announcement opens the door to new hopes: “We will not be able to perform this transplant on the 39 million sick people in the world because it is particularly dangerous, but until now, we thought that a bone marrow transplant and the mutation in question were systematically needed for remission to occur. This seems not to be the case”, adds Sabine Yerly, from the virology laboratory of the Geneva Hospitals.

This 6th remission must be presented this weekend at the International Scientific Conference on HIV, a reference gathering in the field. But the scientific community is already wondering: “How did the virus disappear? Can we imagine remission without a transplant, using the drugs that the patient received during his operation?

New hopes… still very distant

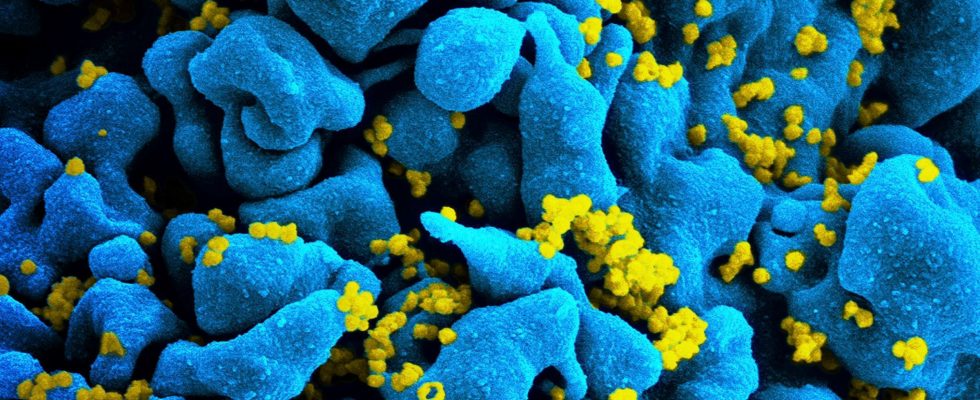

During a bone marrow transplant, cells from the donor attack the immune system of the recipient. Thus, they eliminate cancer cells, killing all kinds of cells in the process, even damaging the skin or the liver of transplant recipients. An extremely violent side effect, but which allows the passage to “empty” the reservoirs of HIV in the body. Still, until now, the few dozen HIV patients who survived bone marrow transplants had seen their infection rebound in the 9 months following the operation.

How then explains that the patient from Geneva still has no sign of resumption of the disease, 20 months later? For the moment, scientists are only at the stage of hypotheses. “Does the transplant in some people empty the reservoir more deeply? Or is the remission due to immunosuppressants, drugs that are administered to limit the rejection reaction? Perhaps it is also caused by a certain type of immune cell, the natural killerpresent in the donor?”, Asier Sáez-Cirión list from the Institut Pasteur.

Biopsy, blood test, the patient from Geneva, described by scientists as an inveterate optimist, agreed to undergo numerous tests for science. The researchers have already been able to check whether the donor has a new mutation in addition to the one already known, CCR5-Δ32, which would also protect against AIDS. In the laboratory, the cells of the Geneva patient were deliberately brought into contact with HIV, to exclude this hypothesis. They fell ill again.