If the world fails to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030, the planet will warm up by at least 1.5°C in a few decades, warned Antonio Guterres, the Secretary General of the United Nations, Monday, March 21. A wishful thinking, as the main polluters – China, the United States, the European Union – are slow to implement the necessary political decisions. The consequences are however known: desertification, loss of biodiversity, melting ice, rising sea levels, but also transformation of fauna and flora in most countries. In France, the forests – which represent 30% of the territory – will thus radically change their face: species will disappear when others will appear.

“The first alerts began in the 2000s, when we observed strong dieback in certain fragile forests, such as that of Hardt in Alsace or Vierzon in Sologne”, explains Brigitte Musch, geneticist in the research-development and innovation department of the National Forestry Office (ONF), the public institution that ensures the vitality and renewal of public forests. Since then, the phenomenon has accelerated. Over the past four years, more than 300,000 hectares – about 30 times the area of Paris – have been affected in public forests. Decline is particularly visible in the Vosges, the Center region, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté and affects both species planted by man and those that arrived naturally more than 12,000 years ago.

Beech is particularly dying in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, with an overall reduction in the number of branches and leaves, which means a lower capacity to capture CO2, sugar, and therefore to make reserves allowing it to restart after the winter. “When spring arrives, we simply wonder which species will survive,” worries the specialist. Softwoods, such as spruces and firs, are also threatened in various regions. “Today, we noted that climate change has an effect on the forest, and that species are already no longer adapted to their regions”, confirms Anne-Marie Bareau, president of the National Center for Forest Property (CNPF) , a public institution in charge of developing the sustainable management of private forests (which represent 75% of French forests).

Dieback of spruce, fir, beech and oak

The problems are manifold. Obviously, the increase in temperatures causes the trees which are not adapted to it to suffer: the lack of precipitation and periods of intense drought induce significant stress, and reinforce the “secondary attacks”. Bark beetles, these small xylophagous insects of the Coleoptera order, can now form four generations between two winters, compared to two previously. And a tree already weakened by global warming is all the more so in the face of attacks by parasites and fungi.

So what will forests look like in 2050? On a European scale, species could become extinct, such as the Zeean oak or the Spanish fir. In France, no species should completely disappear and some forests will even be very little affected, such as that of the Landes, whose pines are particularly resistant, and which remains protected by the maritime climate. But other regions will see their landscape change. “We fear changes especially in the Grand-Est, where the species are not used to droughts”, explains Brigitte Musch. The fir trees, which are already leaving the low altitudes, could die out in areas where they do not have the possibility of migrating higher, such as in the South-East of France or the Jura. And it will probably no longer be possible to see adult beeches in the forest of Sainte-Baume, near Marseille, and far fewer firs, spruces and beeches will populate Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. “The mature species don’t have time to adapt to global warming, which is happening far too quickly, and we wonder whether the following generations will succeed in doing so or not. What is certain is that we will losing genetic resources”, emphasizes Brigitte Musch. Thus, many forests could present a much younger face and more thermophilic species, such as maple.

The mosaic forest and genetic diversification as control tools

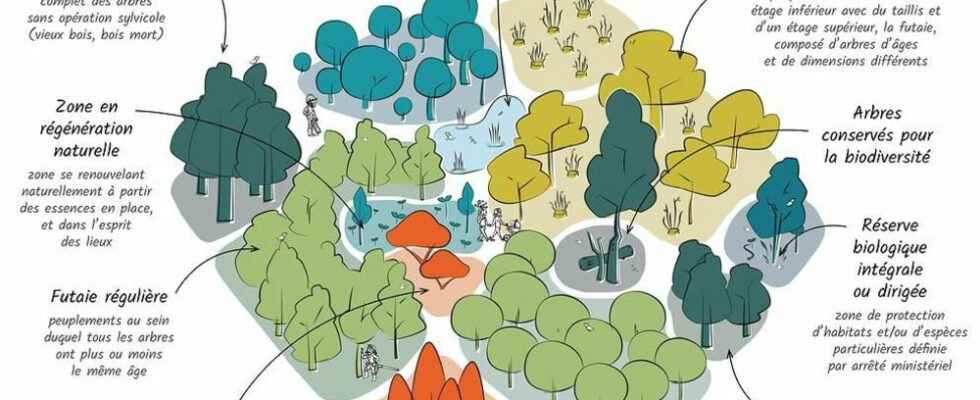

Anticipating the changes to come, the NFB has imagined a plan called “mosaic forest”. The goal is to preserve the health of the forest over the long term, but also its multifunctional aspect, i.e. its ability to simultaneously provide quality timber, protect biodiversity, store CO2, prevent landslides, as well as providing a space for well-being, leisure and rejuvenation. Researchers and engineers have therefore imagined a multiple forest: here, an island of senescence – an area left to evolve naturally until the complete collapse of the trees -; there, an irregular high forest, where trees of various ages and sizes coexist; further on, a wet open area, favorable to the expression of biodiversity, or even an area of preserved trees. Above all, the mosaic forest will shelter “islands of the future” populated by new exotic or southern species, or even French species repatriated from regions where they no longer survive.

The objective of the mosaic forest is to reinforce the diversification of species through experiments carried out in the islands of the future while varying the methods of silviculture.

NFB

“For example, we are going to plant sessile oaks instead of spruces, or try to plant new species, such as Mediterranean fir trees or Atlas cedar,” explains Brigitte Musch. The idea is to carry out experimental introductions, during which we will follow the evolution of new species very carefully, with rigorous protocols to ensure that there is no risk of invasiveness”. , in the forest of Orléans, sessile oaks and Scots pines rub shoulders with pubescent, hairy, or Turkish oaks. If Burgundy-Franche-Comté should keep its beech forests, they will be composed of younger individuals, mixed with more obier-leaved maples for example, when cedars come to dress the suffering fir forests. In these areas, walkers of the future will observe more diversified landscapes, even if it means no longer seeing the emblematic forests, populated by one or two species “What we want to avoid at all costs is to end up with a forest so dying that it no longer shelters the necessary conditions, including humidity, for natural regeneration”, justifies the researcher.

The NFB has also started an “assisted migration” project, in particular through his Giono project. The idea is to select species from warmer regions in order to reintroduce them to areas that will warm up. “In thirty or fifty years, the forest of Verdun will experience the same conditions as that of Manosque, so we have selected sessile oaks from Manosque that we are going to replant in Verdun, betting on the fact that they will mix with local species in order to provide new generations resistant to future climatic conditions”. A way of accelerating the natural migratory process – from South to North – which can no longer keep up with the speed of climate change.

As for private forests, the CNPF is developing many tools for owners, such as Deperis, which measures the decline of plots, or Bioclimsol, which offers a general diagnosis to measure their resilience. “If climate change weren’t so rapid, many trees could adapt by changing the way they function. But since that’s not the case, we need to know which stand is at risk and by when, and send technicians to the field to ensure the correct diagnoses”, explains Anne-Marie Bareau. The CNPF is also experimenting with the introduction of new species and protection against damage from game, which eats young tree shoots.

A first conclusion is obvious: we must diversify the plots. The CNPF invites owners in particular to plant maritime pines in the center of France or in Brittany, and is experimenting with the planting of black pines, Corsican pines, Atlas or Lebanese cedars, holm or Mediterranean oaks with, in the line of sight, “a generally more mixed forest, with more deciduous trees and less conifers”, predicts Anne-Marie Bareau. In the meantime, the French State has already invested 200 million euros for its “reforestation recovery plan”, welcomed by the ONF and the CNPF. Other plans should be implemented by 2030. All that remains is to hope that they will make it possible to save the forests, even if it means changing their faces.