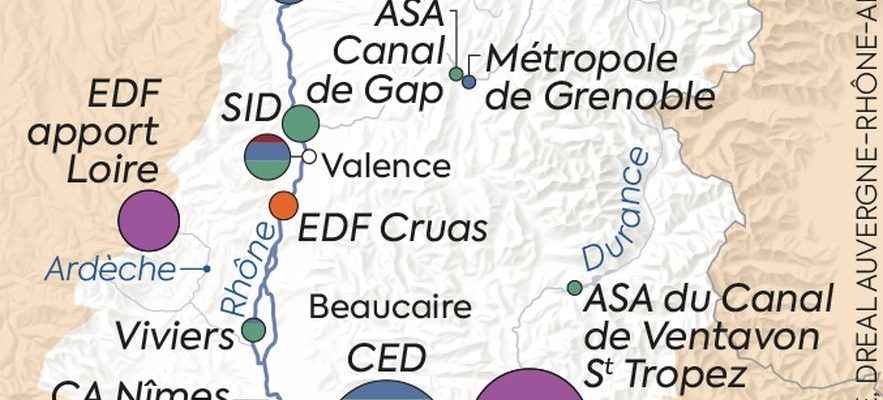

Its meanders, quiet, stretch over more than 800 kilometers through Switzerland. The peaceful appearance of the Rhône, the third longest French river, was nevertheless disturbed at the beginning of March by a study by the Rhône Méditerranée Corse water agency with disturbing conclusions. Between 1960 and 2020, the flow of the river decreased by 7% at the outlet of Lake Geneva and by 13% at Beaucaire (Gard). In question: the increase in air and water temperatures, the decrease in the amount of snow on the massifs and the drying out of the soil. For the future, the projections are hardly optimistic: over the next thirty years, the average flow could be further reduced, in summer, by 20% north of the Camargue. Will the Rhône remain for a long time this “man-eating” river, feared for its violent floods, as mentioned by the academician Erik Orsenna (The Earth is thirsty, Fayard)?

It will certainly remain “in the medium term a powerful river”, notes the agency, but its water “can no longer be managed as an inexhaustible resource”. Its future must be prepared, and the uses of its resource evolve. And in the first place those of the nuclear fleet – the third most water-consuming activity (12%) in France. About half of the power plants today operate with an open cooling circuit. They draw water from rivers and reject it, a technique governed by very precise temperature thresholds. These can force a reactor to reduce its electricity production, or even to shut down, if the discharged water is too warm. However, for this reason the electricity production of the power stations bordering the Rhône could drop by up to 10% in the middle of the century during the most unfavorable months, the report indicates.

The Cruas-Meysse power plant, located north of Montélimar (Drôme) and whose four cooling towers reject their plume of water vapor on this spring day, would not be affected by such a scenario since it operates in circuit closed, a different system that does not depend on the state of the neighboring river. On the other hand, that of Tricastin, located 40 kilometers downstream, could experiment in the future “increased operating constraints”.

3746_CLIMATE_Rhone

© / Legends Cartography

“The Water Is Lost”

Attached to the Donzère-Mondragon canal, a derivation of the Rhône, it needs large quantities of water which it restores in full at a higher temperature of 2 or 3 degrees. But, over the decades, the Rhône has warmed up: from 1960 to 2020 its waters have taken 2.2 degrees in the north and 4.5 degrees in the south. And heat waves complicate the equation: last summer, discharges from the Tricastin site exceeded the authorized temperature limit at least nine times, with the green light from the Nuclear Safety Agency. Biodiversity or energy production: the dilemma begins to take a concrete turn.

On the side of the farmers, whose irrigation of the plots also depends on the Rhône, the concern is already palpable. “Without water, farms are endangered, and the landscape would be completely changed,” says Serge Hugouvieux from his 80-hectare family farm in Suze-la-Rousse (Drôme). “The flow of the river may be decreasing, but our withdrawals are tiny compared to its level, and the Rhône remains the best way to irrigate: the water passes and then ends up in the sea, it is lost”, defends himself. -he.

The 53-year-old farmer is also president of the authorized trade union association (ASA) Irrigation des Grès, a group (a few operators, 950 members in total including communities) authorized to take water from the Rhône. None of the ASAs that pump water from the river had restrictions last year, unlike those drawing water from rivers or groundwater. “But if the decision is made to put everyone on the same level…” Serge Hugouvieux does not finish his sentence. His smile barely conceals his anxieties: “Too many things collide.” Ever more restrictive regulations, the increase in the price of materials, electricity and therefore water… Not to mention a changing climate. “There is little rainfall in winter, not in summer: I have reduced the proportion of irrigated crops, he says.

The Compagnie Nationale du Rhône (CNR) has the means for the long term. This one-of-a-kind player in France is the manager of the river – the concession has been extended until 2041 – for the production of hydroelectricity, river transport and agricultural uses. Since 1934, the CNR has built 19 hydroelectric power stations and as many dams, 14 locks and opened 330 kilometers of waterway. The Avignon lock-factory benefits from a majestic panorama. On this morning, its four red turbines, each equipped with four adjustable blades, follow the established daily schedule. This can be adapted at any time in order to maintain the level, the minimum water level set for the needs of other uses, or to align with electrical demand.

“more marked seasonality”

“On a daily basis, we are already in the perspective of adjusting the machines, optimizing the planning, hydroelectricity being the financial manna of the CNR”, assures David Ferry from one of the floors of the site, located under the river level. “We have passed 2022. So the system is robust”, boasts the territorial delegate of the Rhône Méditerranée management. But it was not easy. In 2022, CNR, which generates a quarter of the country’s hydroelectricity, suffered the same brake as the other players in the sector: a 16% reduction in its production compared to the previous year. Of recent climatic events, Clémence Aubert, head of the strategic management and mission of interest department, retains above all a “more marked seasonality”. This will lead to adjusting production: turbine more when there is water (in winter) and plan for more maintenance during low water periods (in summer).

The closer the Rhône gets to its mouth, the saltier the reflection on the uses of water becomes. Literally. For years, Camargue rice farmers – now joined by the water agency – have been warning about the rise of the “salty corner”, that is to say the sea, in the delta of a Rhône whose power – down – no longer allows the phenomenon to be repelled. Land salinization is accelerating, causing problems for agricultural or drinking water withdrawals. In 2017, the salinity level of tap water in the coastal town of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer had exceeded the authorized threshold for several days. “At the end of February, the level of the Rhône was that of a month of July”, deplores Lucien Limousin, mayor of Tarascon and vice-president delegate for agriculture and the territories of the departmental council of Bouches-du-Rhône. What revive the fears of a new distribution of bottles of water for the inhabitants.

Agriculture undergoing the same risk, “we are asking ourselves the question of modifying the sampling station in the southern Camargue”, notes François Clément, director of the French Rice Center. Salt water has a higher density than fresh water. The first therefore slips under the second when it rises in the bed of the Rhône, destabilizing the existing pumping points. “I did not think that the effects of climate change would manifest themselves so quickly,” admits Bertrand Mazel, president of the Syndicate of rice growers in France. The latter have begun to adapt their methods: new irrigation techniques, postponement of the date of sowing, research into varieties more resistant to salt… The sector is now calling for “more courage from the public authorities”, who are slow to take the problem seriously. arm-the-body and proposes in particular the construction of dams against salt. “The debates on water sharing are just beginning,” says Bertrand Mazel. The sight of the Rhone, which flows, impassive, a few hundred meters from his office, no longer has the same soothing power.