In the war that does not speak its name between Russia and the European Union, a new front has opened on the eastern borders of the NATO zone, east of the Black Sea. In Georgia, the deputies of the pro-Russian majority Parliament who put their law on “foreign influence” to the vote for the second time in a year, after having backed down the first time in the face of popular protest, did so with the knowledge of cause. They knew that its adoption would ignite the powder: modeled on that in force in Moscow, this “Russian law” is used as a means of eliminating the opposition by forcing people to declare as an “organization serving the interests of a power foreign” any association or press organ for which 20% or more of its funding comes from abroad. In Georgia, the same law could be used to repress opponents of the government, particularly before the legislative elections scheduled for October.

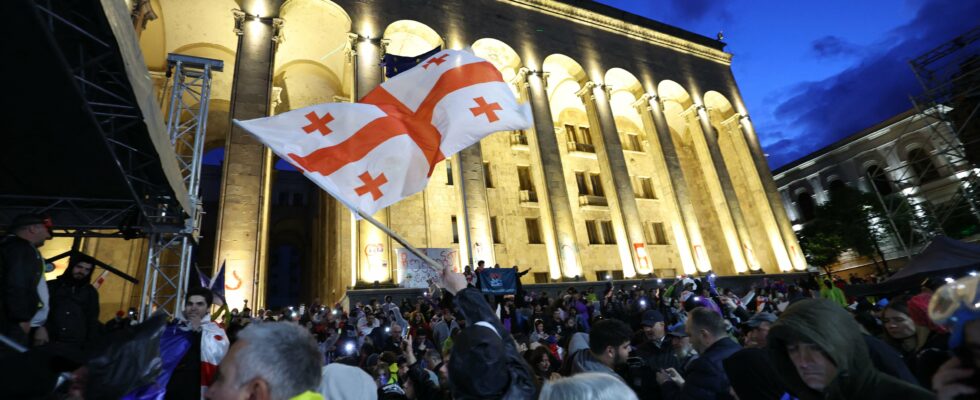

Faced with those they had elected on promises of anti-corruption, tens of thousands of Georgians invade the streets of Tbilisi every evening brandishing the European flag to contest their vote. They are no longer unaware of the strategy of the Georgian Dream party, founded by an oligarch in the service of the Kremlin, which supports the government. They know that the “Russian law” is now returning to Parliament only because it fits into the precise context where the European Union, in December 2024, granted Georgia candidate status. Its final adoption would hamper Georgia’s accession process to the European Union. The veto that President Salomé Zourabichvili will oppose will not change anything, since Parliament will easily have a two-thirds majority to override it.

In the meantime, the incessant demonstrations place Georgia at the tipping point, between revolution and repression, in a scenario very similar to the Euromaidan protest movement in Ukraine, which, in early 2014, led to the flight of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych, then the annexation of Crimea, the aggression in Donbass and the all-out war in Ukraine.

Hybrid Warfare

This new eastern front is part of the hybrid war system led by Vladimir Putin. It confronts European leaders and Brussels institutions with their contradictions, at the very moment when the war in Ukraine is testing their principles and their model of values as much as their ability to mobilize. If this potentially repressive law is adopted, should the EU be flexible on its membership criteria at the risk of harming its credibility? Should it, conversely, renounce integrating Georgia in the name of its principles, at the risk of punishing a population estimated to be 80% pro-European as well as its president Zourabichvili, of opposing a democratically elected government and thus throwing into the arm of Putin, as a trophy, the rest of the country that he has already partly occupied since 2008?

How, finally, could the European Union block Georgia’s accession process when it accepts that Aleksandar Vucic’s Serbia, also a candidate for the EU, openly supports Moscow and has missile batteries delivered to it? ground-to-air by China, and signs a free trade agreement with it? How can Europeans claim to assert their principles by letting Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, a member of the EU and NATO, taunt both the EU and NATO by proclaiming his support for Putin and Xi Jinping ? Why would the European Union refuse to Tbilisi what it tolerates from Belgrade and grants to Budapest?

It’s a headache, and that’s Europe’s weakness. It is hardly surprising that the heads of state or government cannot even agree on a joint declaration condemning the law on foreign influence as contrary to their values. As expected, Hungary, supported by Slovakia, opposed it: the EU, she argued, should not interfere in the internal politics of a third country. The detestable assassination attempt on Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico adds to the confusion of a polarized and white-hot Europe where both camps watch, dismayed or delighted, each new outbreak of fire.

Marion van Renterghem is a senior reporter, winner of the Albert-Londres prize and author of “Piège Nord Stream” (Arènes)

.