The team that developed the new method stated that millions of male chicks are killed every year in the UK right after they are born because they do not lay eggs, and this may no longer be necessary.

The British government will also examine the use of gene editing technology in the livestock industry.

A gene becomes ineffective

This new method, announced in an article published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, enables a gene to be turned off during embryo development.

With a series of genes that come into play in the very early stages of embryo development, when they are still between 16-32 cells, the development of mice with unwanted sex ends at that level and can be prevented.

The researchers announced that this technique can also be applied to farm animals, and that they are negotiating to start a pilot program for this purpose at the Roslin Institute in Edinburgh, one of the world’s leading gene editing centers.

Speaking to the BBC, Kent University’s Dr. Peter Ellis says that if this method, which is applied in the laboratory, is applied commercially, it will make an important contribution to animal rights:

“Every year, 4-6 billion chicks are killed worldwide. We can prevent them from suffering.

“Male chick embryos can be made to not develop at all.”

A large number of lab rats are also killed each year in the UK because they are not born to the desired sex.

At the Francis Crick Institute in London, Dr. James Turner says that they have found that only male or female mice are used in nearly 25,000 scientific articles published in the last five years:

“Each experiment requires a different number of mice. But we can estimate the total number of mice used to be around 100,000.

“This method can be used immediately in scientific laboratories.”

Another report published this week in the UK emphasized that the regulation that enables genetic editing of farm animals is essentially to improve the conditions of animals.

Peter Stevenson, from the NGO Compassion in World Livestock, says that they are generally wary of gene-editing technologies because of their efforts to fabricate livestock, but they support the ability to decide on the sex of chickens:

“We support the use of this practice for animal rights. By ensuring that chickens only have female chicks, we can prevent millions of unwanted male chicks being killed in the UK each year.”

Barney Reed of the UK’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals emphasizes that this technology must be tightly regulated:

“We should not forget that many proposals for animal rights or the environment are actually suggestions for solutions to the problems we have created.”

Dr. Ellis says that this should be discussed in every aspect in society before it is used in livestock:

“Scientifically, we are not at the point where we can apply this in animal husbandry yet.

“Gene editing tools for different species must be developed first, and then checked to see if they are safe and effective.”

HOW DOES IT WORK?

The sex of a mammal is determined by its sex chromosomes.

Females have two X chromosomes, one inherited from their father and one from their mother.

Men have one X chromosome from their mother and one Y chromosome from their father.

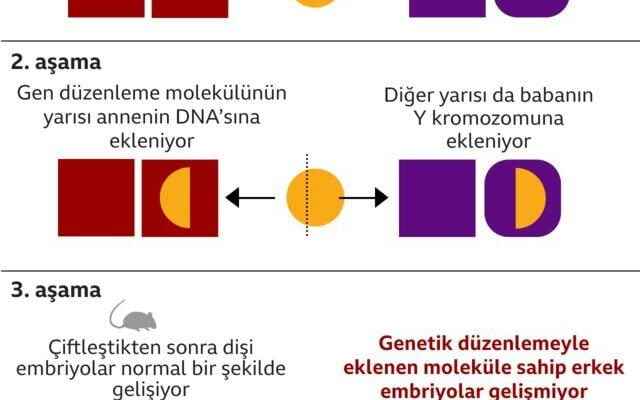

A gene-editing molecule called Crispr-Cas9, which disables genes, inserts half of it into the mother’s DNA and the other half into the X or Y chromosome, depending on which sex offspring are intended, the researchers said.

When the two halves of the molecule come together, the development of the embryo stops.

For example, when scientists wanting a female mouse add this molecule to the father’s Y chromosome, when the X and Y chromosomes come together, the embryo’s development stops, and thus no male offspring is born.

When it is aimed to give birth to male mice, the molecule is added to the father’s X chromosome.

Mice usually kill 3-12 puppies at a time.