Philippe Delerm, writer

“We loved sadness”

1964. The year I turned 13. The first year of my passion for sport. The year of the Tokyo Olympics. The year of melancholy. The Jazy year. It’s an understatement to say that we were waiting for these Games of the Empire of the Rising Sun. All year round, all these blankets. Sports magazines, of course. But also those of Paris Match. And two undisputed stars: Kiki Caron, Michel Jazy. Christine Caron, the brand new teenager – but at the time, swimmers were often teenagers. And for Jazy, the age of maturity, the almost promised victory in the 5,000 meters. Beaten by Kathy Ferguson, who broke the world record in the 100 meter backstroke, Christine will have a magnificent gesture. On the podium, raising her head, she will see that her rival was crying with emotion during the American anthem. And she took her hand, as if to console her for having beaten her.

We had Jazy left. Jazy on the radio, because television did not broadcast events contested with such a time difference. Jazy on the little blue and white transistor radio that I received for Christmas. It was raining in Tokyo that morning. Enough to raise hopes a little, because the beautiful, elegant and long stride of Michel Jazy would not cope well with too heavy a ash. Did he feel too strong, was he a little afraid? When he attacks just after the bell, almost a lap from the finish, we of course share the announcer’s excitement, but at the same time we say to ourselves that it’s much too early. It’s way too early. At the start of the final straight, the American Bob Schul overtakes him, then the German Norpoth, and even the second American Dilinger. But we feel that the French champion has given up. He only wanted victory.

There were no world championships. The only world title in athletics was the Olympics. It’s a long time, four years. Certainly, in 1965, Jazy will beat all the records, and all his opponents. But his sadness from Tokyo is irremediable. There is this photo where he is prostrate, both arms resting on a metal barrier. I will have a hard time convincing my editor that it is indeed this photo that I wanted, on the cover of my album on the beautiful moments of sport. Jazy is not alone in this photo. We didn’t necessarily like the winners that year. We loved Raymond Poulidor, narrowly beaten in the Tour de France. We loved Christine Caron. We loved Michel Jazy. We loved sadness.

Marylise Léon, general secretary of the CFDT

“The Lord’s Footstep”

My first memory of the Olympic Games is first of all this incredible slender figure dressed all in red who seems to be gliding on the track. I look fascinated at this athlete who is described to me as the fastest man in the world. It was 1984, I was 8 years old. Carl Lewis was not well known to the general public. Even less of the little girl I was.

However, I perfectly remember his long strides, his intense look before the start of the race and his haughty bearing that some considered contemptuous. I saw incredible determination and class, a lord. A man who showed no emotion and who collected medals. Four. Four in a single Olympiad. He joined Jesse Owens.

I don’t think I realized the feat he accomplished that year. The Los Angeles Games took place in very special conditions. The Cold War was at its peak. The USSR reciprocated the United States by boycotting the Games that the latter had shunned four years earlier in Moscow. Carl Lewis reigned supreme at Memorial Coliseum. And I launched myself onto the sand of my favorite Finistère beach, multiplying the sprints and leaps in front of an imaginary audience.

François Hollande, former President of the Republic

I have a lot of memories of the Olympic Games, I also have the memory of what they represented when I started to become interested in them. Notably Alain Mimoun and Michel Jazy who had been great athletes. But the first Games that marked my childhood were those of 1968. Firstly because it was during a period when everything seemed turned upside down, then because it was in Mexico, at high altitude. We were convinced that France had little chance of winning medals. Also, when in front of my television set where color had just been introduced, I was able to witness Colette Besson’s victory in the 400 meters, this race filled me with joy and happiness.

“Because for a long time, the Olympic Games were virile images, records that belonged to only one genre. What mattered was to highlight men”

This woman had shown considerable energy. She had isolated herself in Font-Romeu. She had taken a tent to camp in and prepare. She was far from being the favorite and she upset all the predictions in an exceptional finale. That’s the wonderful thing about athletics. Particularly in a 400 meters which is neither a sprint nor a middle distance and which, in just 50 seconds, keeps you in suspense. Colette Besson’s victory was a symbol. She was one of the first French women to win a gold medal, it was unexpected. Additionally, another compatriot, Nicole Duclos, was her most prominent rival. These two champions allowed this sport to find its rightful place, equal to men.

Because for a long time, the Olympic Games were virile images, records that belonged to only one genre. What mattered was to highlight men. For the first time with Colette Besson, a champion and her female achievement were recognized and her medal encouraged the involvement of women in sport. Since then, other champions have collected medals, such as Marie-José Pérec. I have no doubt that in Paris this summer other exploits will be remembered for a long time in the memory of a generation aware that the fight of women is also an Olympic value.

Vincent Duluc, sports journalist and novelist

“Morelon on the carpet”

The summer of 1976 was that of Kornelia Ender, four gold medals in swimming, a blonde queen of the GDR at the crossroads of several mythologies, who had marked my adolescence and about whom I would write at length a little later. But it was, for a Bressian childhood, that of Daniel Morelon’s defeat in the speed final in track cycling, which left me inconsolable.

He was the champion of my territory, double gold medal in tandem and speed at the Olympic Games in Mexico, again crowned in speed in Munich, four years later, and entered alive in a column by Antoine Blondin as “need bressan “. All of Bourg and all of Bresse awaited his coronation in Montreal, his pass of three. I have never forgotten the name of his executioner: Anton Tkac. A Czechoslovak. The speed then created several parallel suspenses: the sessions of standing still at the top of the track, the guys who dived from afar, those who “jumped” their opponent on the line. One round each, and in the third, gold at stake, Morelon in the wheel, in an armchair, but by the time he got up, Tkac was gone, he would not come back. The year 1976, after the defeat of the Greens in Glasgow, told us that life would be unfair.

François Villeroy de Galhau, governor of the Bank of France

“The heroic rise”

The Olympics for a central banker could firstly be a story of gold and silver… But above all it is a collection of unique emotions. The most recent comes from a little-known discipline: the decathlon, and from Kevin Mayer who is more famous. In Rio in 2016, then in Tokyo in 2021, he showed the genius of the second day’s comebacks, from the pole vault to the javelin then the 1,500 meters… finishing each time with the silver medal. I love his tenacity for over ten years, including in the face of injuries; I love that he alone saved the honor of our athletics in Japan… and that his paternal family comes from my dear Moselle.

/ © STEPHANE KEMPINAIRE / KMSP / AFP

But my oldest emotion is Grenoble 1968 and the Winter Games. The bad TV – rental – had just arrived at our house, its terrestrial snow made the slalom almost invisible… and Jean-Claude Killy’s third gold medal remains shrouded in a certain mystery. That day, the child in me caught the Olympic bug.

Axelle Lemaire, former Secretary of State, CSR Director of Sopra Steria

“Athletes like any other”

“80,000 people went wild to cheer the Paralympic athletes during the London Games in 2012. The French were beautiful, powerful, and I was like crazy when Marie-Amélie Le Fur won the 100 meters. For the first time, these athletes were seen by the media as professional athletes with a disability, and not as disabled people who play sports.”

Benoît Bazin, CEO of Saint-Gobain

“The Olympus of Mimoun”

I remember long summers when, as a teenager, I spent the months of July at home in Caen before going on vacation in August with my whole family. I divided my days between playing the cello and trips to the town library with my brother. What we liked best was seeing and rewatching VHS tapes depicting the best moments of the Olympic Games.

/ © AFP

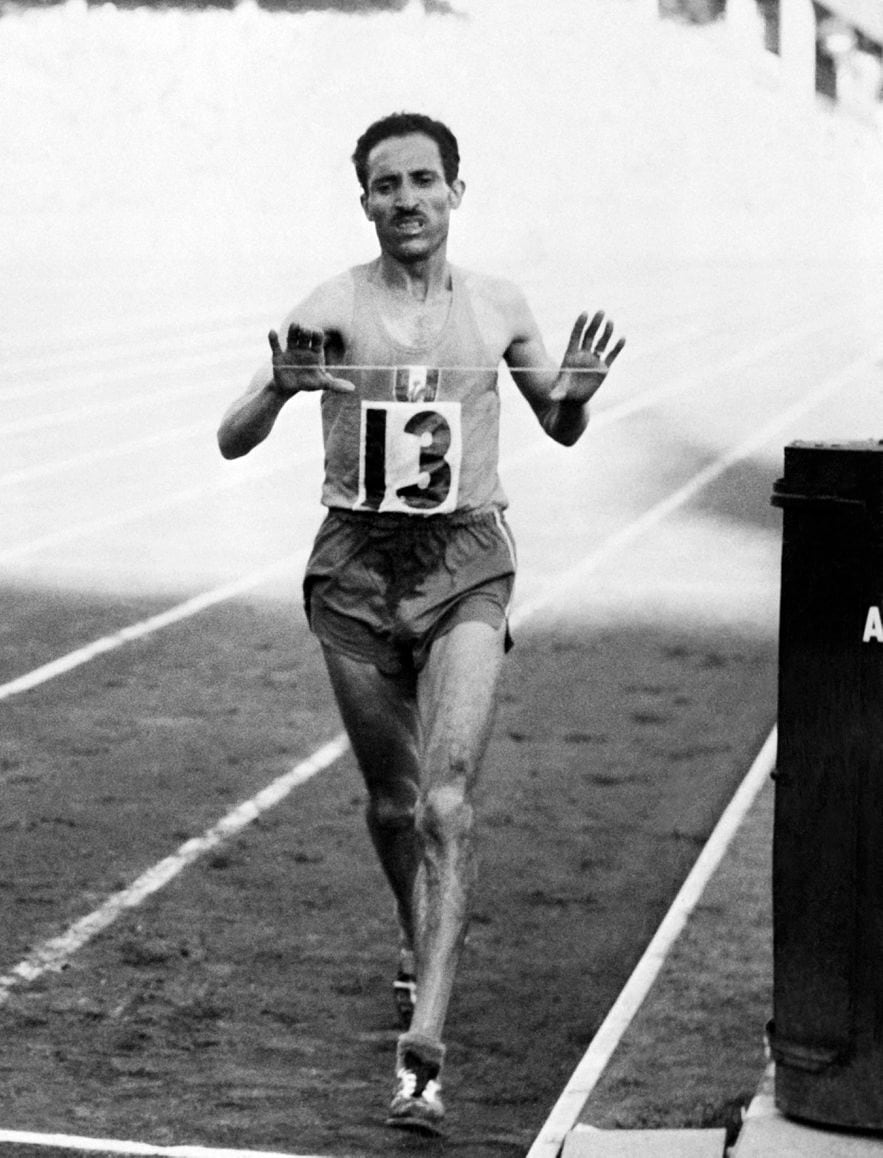

I discovered Alain Mimoun’s race in the marathon at the Melbourne Games in 1956. That day, the former master corporal born in Oran, who had almost lost a leg during the Battle of Monte Cassino during the Second World War, is cheered by 120,000 spectators when he enters the stadium, in scorching heat. With his bib number 13, he ran for France in the middle of the Algerian War. To draw strength after the 35th kilometer, he said he never stopped thinking about his daughter born the day before thousands of kilometers away, and whom he and his wife had named Olympe. At the Caen library, I had tears in my eyes when I discovered Mimoun’s epic.

Maylis de Kerangal, writer

“The Comaneci Angel”

“[…] I remember very precisely the moment when she appeared in front of the uneven bars, under the lights of the Forum, the construction of which was unfinished. The white leotard with the V-neck, the white slippers, the awkward little bangs, the protruding shoulder blades under the elastic fabric. And on his back, the number 73, like a golden number.

I remember his first movement as a feeling of dizziness, an initial apnea. My heartbeat is speeding up, I have a lump in my throat and my legs feel like cotton. My eyes struggle to follow it, to decompose these figures which follow one another without pause, fluid, ample, ultra-rapid. She moves above, between and below the bars, forwards, backwards, with her pelvis high, her arms thin and her toes outstretched. Its arch apostrophes the world until the final angel’s leap. Beauty in person.

I remember as if it were yesterday the presenters babbling, their comments reduced to flat exclamations – oh, look at this, she’s moving well! Of their mad astonishment. […]

I remember with a sinking heart the two-tone ribbon moving in her little ponytail, the only trace of indiscipline on this strict, refined, controlled body. A body that I do not know, which is neither that of a little girl, nor that of a woman, nor even that, overflowing, awkward, transitory, of an adolescent girl. He overthrows the established order, he makes a revolution. It hybridizes childhood and power. This body is the event […]”

Taken from I remember… Pérec’s stride (and other sporting madeleines), directed by Benoît Heimermann. Threshold, 226 p., €19.90.

.