“When there is no longer an axis, everything is out of alignment!” warns an observer at the heart of European power. Far from being confined to the two banks of the Rhine, the ups and downs of the Franco-German couple also animate the debates in Brussels. The terms “axis” or “engine” are however preferred to that of “couple”, because they describe more finely the role of Paris and Berlin in the manufacture of compromises at twenty-seven.

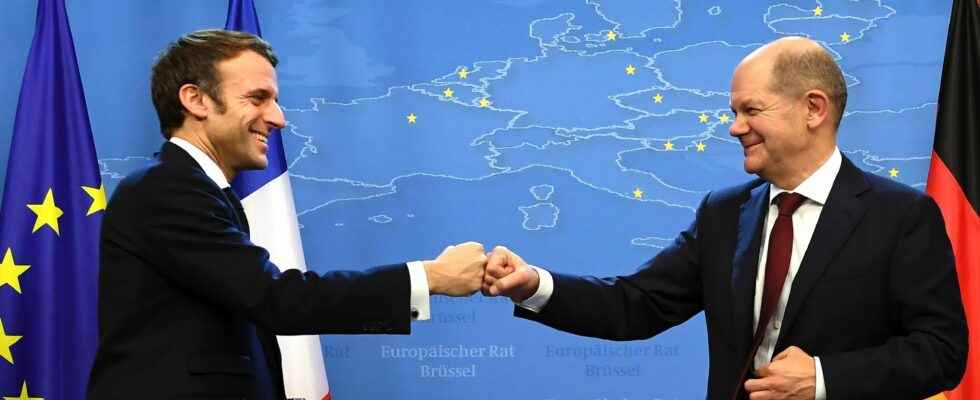

“Franco-German is a working method for creatively overcoming ideological oppositions”, underlines a high-ranking source at the European Commission. Emblematic example: the May 2020 agreement between Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron which paved the way for a historic recovery plan of 750 billion euros, financed by joint debt.

On most subjects – economy, defence, international trade – the two European powers start from opposing points of view, which structure the space in which the others position themselves. “Since the departure of the United Kingdom, this informal axis has become even more important to build bridges between the east and the west or between the north and the south of Europe”, analyzes the Romanian MEP Dacian Ciolos. “When you lead another country, you have to use their agreements or their differences. If they are not on the same line, it becomes easier to build an alliance to block a text”, continues the one who was Prime Minister in Bucharest in 2016. Even if it is often criticized, the Franco-German leadership is still awaited by the other capitals. “Paris and Berlin have the responsibility to put themselves in overhang”, deciphers a diplomat.

“There is a German problem”

In recent months, their disagreement has not gone unnoticed. But the accusing fingers rather point to Berlin. “There is not a Franco-German problem, there is a German problem, even a Scholz problem, annoys a source from a founding country of the Union. The Chancellor is struggling to extricate himself from his interests nationals.” The most indulgent recall that Germany must review its fundamentals, from energy policy to its trade relations with China, as three parties govern together in Berlin for the first time.

Obviously, this period of apprenticeship comes at a bad time, given the international context. However, if the French are impatient not to advance at a forced march on the subjects that are close to their hearts, such as defense or the reform of the electricity market, the other Europeans remain more philosophical. They point out that Paris and Berlin remain aligned on the most important: Ukraine and Russia.

In any case, a file will allow us to quickly take the temperature between the two capitals: the calibration of the European response to the American plan to reduce inflation (IRA) whose massive subsidies threaten the competitiveness of the industry of the Old Continent. How to draw a quick and effective response? This is the hot topic of “Franco-German” before the meeting at twenty-seven in early February.