His outings in the field have become rare since the forced passage of the pension reform. On April 14, Elisabeth Borne made a trip to Hips, in Eure-et-Loir. The theme of the day? The purchasing power of the French and the rise in food prices. In the morning, the Prime Minister goes to a Hyper U. Between two fruit and vegetable departments, the tenant of Matignon, surrounded by an army of communicators, boasts somehow of the measures taken by the government, under the boos of demonstrators who have invited themselves to the party.

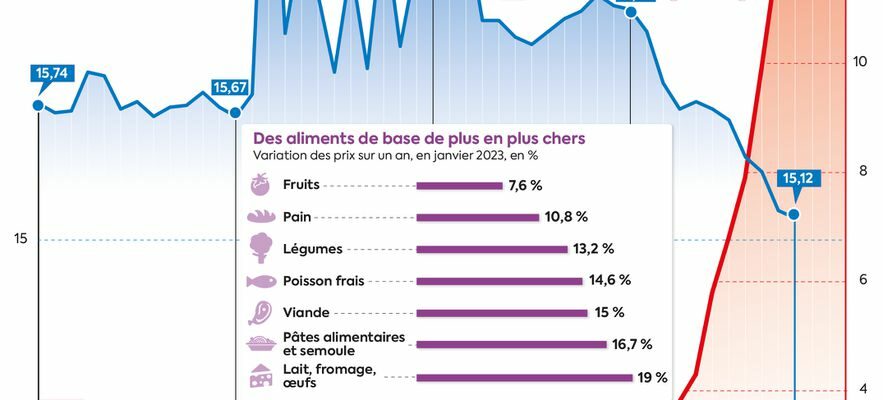

A sentence, relayed in a short video extract on his Twitter account, does not go unnoticed: “What we see today is that prices have fallen by 5%”. In March, food prices nevertheless increased by 1.6% compared to the previous month, the increase even rising to 15.8% over one year. Hundreds of Internet users, including several opposition politicians, supported by INSEE figures, do not miss the opportunity to point out to him, proof that the subject tenses the debates. In reality, Elisabeth Borne only mentioned the products of the anti-inflation basket put in place since the beginning of March, but the extract published by her team was truncated. In its brands, System U, for example, indeed offers 150 products at cost price, when Carrefour sells 200 products at less than 2 euros.

No crisis “profiteers”, really?

Whatever, the portfolio of the French has still taken a big hit in recent months when going to the supermarket checkout. And it’s not about to stop. “The new prices negotiated since December have passed, but only apply from March. Before applying them, distributors must first sell stocks. Talking about red March was nonsense. We will see an increase prices until the end of the summer”, warns Frank Rosenthal, consultant specializing in trade and mass distribution. So, this nagging question returns: has a sector taken advantage of a windfall effect to increase its margins and revenues? The question needs to be asked.

In a report published on March 3, the General Inspectorate of Finance concludes that the rise in food prices between 2019 and the first half of 2022 is largely due to the increase in the prices of inputs – agricultural materials, energy, transport, labor – used by all actors in the value chain: “In total, [elle] results from the combination of several factors: war in Ukraine, post-Covid recovery, global warming, animal health crisis and various factors of an economic nature (competitiveness of the economy, labor shortage)”. Above all, the service interdepartmental inspection de facto rules out the existence of crisis “profiteers”.

This report, however, does not take into account the second half of 2022 and the start of 2023. In another study published a few weeks ago, the economic studies institute Rexecode was less categorical: initially, corporate profitability was squeezed, before increasing significantly at the end of last year. “Margins in the distribution sector have not exploded. Most of the price increase comes from suppliers,” adds Eric Dor, director of economic studies at IESEG.

A battle of arguments

On both sides, the arguments diverge. Each actor actually defends his own chapel. It must be said that the negotiations between the two sectors turned into a rat race: the industrialists demanded for several months increases in prices deemed too high by the distributors. Finally, an increase ranging from 10 to 12% was agreed to the snatch. “For years, there was very little increase. There was a windfall effect for the benefit of manufacturers who passed on the price increases. In the future it will be much more complicated to do so” , emphasizes Frank Rosenthal. But the tension has not subsided, far from it. Since the beginning of the crisis, it is Michel-Edouard Leclerc who has become the spokesperson for his sector. On France Inter, on April 19, he again stepped up to denounce the lack of transparency of manufacturers. “We remain on an exercise of negotiations between commercial actors, it is quite logical that there is a game of actors and that the transparency is not total. But we are not around the table to negotiate”, tempers the office of Bruno Le Maire.

3740_SONAR

© / Art Press

The new exit of the leader does not surprise the opposing party. “Leclerc is both our client and our competitor. We have different systems, these are setbacks. Michel-Edouard Leclerc has always fought to defend the lowest prices and that allows him to fuel this positioning There are many things in his statements in which the line is really forced”, criticizes a large French industrial group which recognizes however: “We had to pass on the rise in production prices, we could have absorbed more but that would have obliged to make compromises on our products or our production choices. Conversely, we have made commitments to support a sector, improve our recipes, our products”.

Soon a return to the negotiating table?

But the situation is no longer the same as it was six months ago, when negotiations began. The price of wheat has returned to a level below that before the war in Ukraine, as have oil and coffee, while the decline in energy prices is confirmed. From now on, Bruno Le Maire and Olivia Grégoire are calling on distributors and manufacturers to get back around the table to renegotiate prices. “A charter was signed between the participants last year: it was agreed that negotiations should be reopened in the event of price drops. this symmetry clause applies”, specifies the cabinet of Bruno Le Maire. The Minister Delegate for Industry, Roland Lescure confirms: “Inflation is the fight of the year, all players in distribution and the agri-food sector must mobilize to limit the impact of rising costs on the prices. The State has done its part of the job”.

For the moment, it is on the side of the industrialists that it gets stuck. “Distributors are more inclined to play the game, they are playing on their image with their customers. They are not the ones who greatly increase their margins. these are multinationals that sell to all countries in Europe, even the world, they are more difficult to domesticate. Bercy has more weight with French distributors, “said Eric Dor.

The distributors are in any case ready to come back around the table as soon as possible. But the squabble with the industrialists starts again. “Last year, when raw materials increased, we very quickly reopened negotiations to take the increases into account. We would like what happened in one direction to happen in the other”, launches Thierry Desouches , the spokesperson for the Système U group. It’s a whole industry that feels aggrieved. “The reality is that today there is a desire on the part of manufacturers to take advantage of the situation to increase their margins”, denounces Jacques Creyssel, director general of the Federation of Commerce and Distribution.

The shared agricultural sector

In the meantime, between the two, the agricultural sector is brooding and fears that the situation will return to the way it was before after an initial improvement. “There is a little music that goes up: if the prices of certain inputs go down, then the prices of products should go down immediately, that gives us pimples. We are flabbergasted that Bruno Le Maire can sit down like this on the EGalim laws and tell distributors not to take them into account”, laments Patrick Bénézit, vice-president of the FNSEA. The Law “for the balance of commercial relations in the agricultural sector and healthy and sustainable food” aims to ensure and protect the income of farmers. The powerful agricultural union says that many sectors are not covering their production costs despite the increases that have been passed.

Same story from the side of the large industrial group that we interviewed: “When we see the state of French agriculture and the difficulty in renewing generations, it is not desirable to return to a totally deflationary policy. for a moment we say that we want to revitalize the French industrial fabric, it is important to make the right choices, to ensure that we create outlets”. A government adviser, however, warns against the manipulation of large industrial groups: “We must not be fooled. Let’s be careful not to fall into the trap. message. We are not convinced that Unilever or Ferrero, who are cutting back a little on their margins, will hinder the Beauce farmer”. André Sergent, president of the Regional Chamber of Agriculture of Brittany, mitigates the situation: “At the agricultural level, our production costs have certainly increased, but we still have sales prices which are increasing”.

French food sovereignty in danger?

For Roland Lescure, the problem is elsewhere: “The major challenge is in export. When we fight between contractors on a national scale, we will share a cake which tends to shrink. I would like distributors and manufacturers organize themselves so that we can find French products abroad, rather than bickering in public like that”. The burning issue of food sovereignty also comes into the debate, a challenge that seems to have taken a back seat in recent months. “To have food sovereignty, you have to produce in the country. We are lucky in France and especially in Brittany, to have a very favorable climate for farming. Imports of agricultural foodstuffs are at unprecedented levels. Our fear is that consumers will turn to foreign import products”, explains André Sergent.

Who to give reason to? The return to the negotiating table promises to be strewn with pitfalls in any case. “They are going to see each other again with more or less good will. It will probably start at the beginning of the summer. If you don’t sell the stocks, you are not going to lower the prices right away. It will not come back in any case at the pre-inflation level”, anticipates Frank Rosenthal. Within the industrial sector itself, voices diverge. “When we talk about manufacturers, there is not a single industrial population, there are multinationals, SMEs and VSEs. Those who are most comfortably installed are the multinationals. They have comfortable margins, which are largely inflated. They do not really want, at least their shareholders do not want to reopen negotiations”, assures Thierry Desouches. On arrival, it is the consumer who will pay the bill.