Before the emergence of modern medicine, disease transmission was explained by miasmas. With the work of Louis Pasteur and other hygienists, this thesis of “bad air” will gradually become synonymous with obscurantism. When Covid arrived, the dominant frame of reference was therefore still centered on the importance of hand washing to prevent the spread of infectious pathologies. Hence the initial difficulty for some of the experts – even within the World Health Organization – to imagine that contamination by Sars-CoV-2 passes at least in part through aerosols emitted by breathing. , which can remain in suspension in the air of closed and poorly ventilated places.

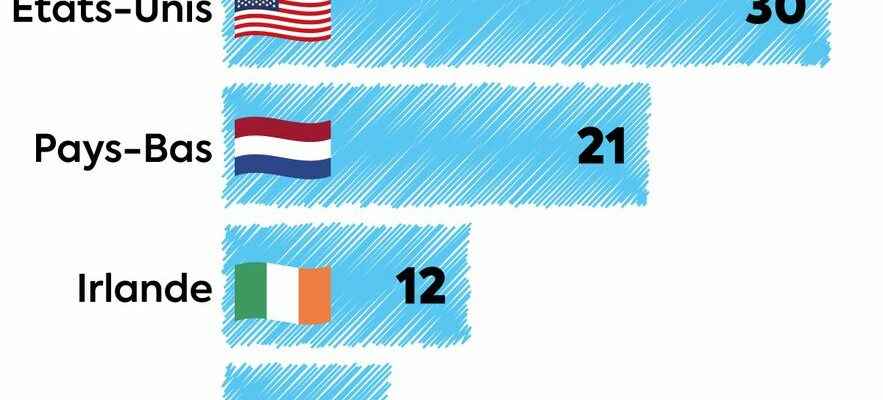

Since then, scientific studies have accumulated, and the dogma has changed. “This pandemic has shown the importance of ventilation, against Covid, but also all respiratory infectious diseases”, recalls Professor Arnaud Fontanet, epidemiologist at the Institut Pasteur and former member of the scientific council. In the United States, this awareness has resulted in a vast investment plan, presented on December 8: 472 billion dollars made available to institutions and individuals to “improve the quality of indoor air and reduce the spread of Covid-19 and other airborne diseases”. In Belgium, a recent law obliges places open to the public to equip themselves with CO2 sensors to continuously measure air quality (a low rate shows good renewal) and, from 2025, to inform customers results. Canada, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and Australia are investing in the ventilation of schools, according to data from the “We are aerating” collective.

And in France ? During the election campaign, candidate Macron announced “a massive effort to purify the air in all our schools, our hospitals, our retirement homes and in all public buildings”, with first results by the end of 2022. The only concrete translation at this stage: 130,000 CO2 sensors for schools and two decrees published at the end of December. These texts lower the limit values of carbon dioxide present in the air in places receiving children, with a measurement once a year and a “self-diagnosis” of the installations every four years. “Children must be given priority, because it is complicated to make them wear a mask when they are contributing to the spread of Covid, influenza or bronchiolitis. But the sensors do not seem to be in sufficient number and it would above all be necessary to effective ventilation measures”, regrets Professor Brigitte Autran, immunologist and president of Covars (Committee for monitoring and anticipating health risks).

A “massive effort” that is long overdue

The task promises to be immense: “According to the latest data from the Indoor Air Quality Observatory, 84% of kindergartens and 51% of elementary schools had at least one room with very confined air, and in the three quarters of the establishments, there is no ventilation system”, recalls Fabien Squinazi, president of the specialized commission for environmental risks at the High Council for Public Health (HCSP). In reality, everything depends on local elected officials. In Arras (Pas-de-Calais), the town hall has equipped all classes with sensors, when Périgueux (Dordogne) bought five of them for all of its schools, for example. Some communities have also acquired air purifiers, although their effectiveness remains to be demonstrated.

Ventilation is struggling to establish itself in schools in France.

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

“If opening the windows often proves impossible or too restrictive, then mechanical ventilation remains the best option to fight against infectious diseases, but also to preserve cognitive performance, which is known to decrease in an atmosphere that is too confined”, continues Fabien Squinazi. The cost ? “Around 5 euros per child per month, installation and maintenance included”, estimates Frédéric Bouvier, director of the Air skills center at Véolia. Prohibitive, according to Delphine Labails, mayor of Périgueux and co-president of the education commission of the Association of Mayors of France: “Since last year, this work can benefit from state subsidies, but it remains heavy for the municipalities ” .

Outside the schools, the “massive effort” is long overdue. “The regulations applied to childcare facilities should gradually be extended to other buildings”, assures Fabien Squinazi. However, it is unlikely to change the situation: “We limit ourselves to self-diagnosis and occasional measurements, without control”, regrets an expert. Because despite the Covid and calls from scientists, indoor air quality has never become a priority. “This issue is not visible and does not cause an acute crisis, so it does not mobilize”, notes Mélanie Heard, head of the health center of the think tank Terra nova, and author of a note on the subject. Many actors, however, take care of it: an observatory, the Scientific and Technical Center for Building, ANSES, the HCSP or even Ademe. Probably too much: there is a lack of a national strategy with “solid governance”, notes the HCSP in its recent evaluation of environmental health policies.

Scientists mobilized

“Without strong action from the State, with communication, budgets and support, nothing will happen”, regrets Pascal Morenton, teacher at CentraleSupélec and member of the “We aerons” collective. Despite the indifference of a large part of the public and the authorities, scientists are not giving up. The epidemiologist Antoine Flahault, who has been pleading for months for a ventilation policy, will publish a synthesis of the literature: “Several concordant studies confirm that it reduces contamination”, he underlines. For its part, the ANRS-Mie (National Agency for Research on AIDS and Emerging Infectious Diseases) has just launched two working groups on the transmission of infectious respiratory diseases.

“We guess that the investments to have an interior environment as safe as possible are considerable. The public authorities will need strong evidence to arbitrate between different priorities, and if common sense pleads for the quality of the air, there are still gaps in knowledge”, indicates Professor Fontanet, who will lead this work. On the menu: physiopathology of transmission (how the virus spreads and infects us) and evaluation of intervention strategies against the virus, with randomized population trials. “It is obvious that we are doing this to get things moving,” confirms Professor Yazdan Yazdanpanah, director of ANRS-Mie.

“In the 19th century, it took more than fifty years to convince that cholera passed through water rather than miasma and that it was necessary to distribute clean water to overcome this disease”, recalls Professor Flahault – hoping that we won’t have to wait so long for the air quality…