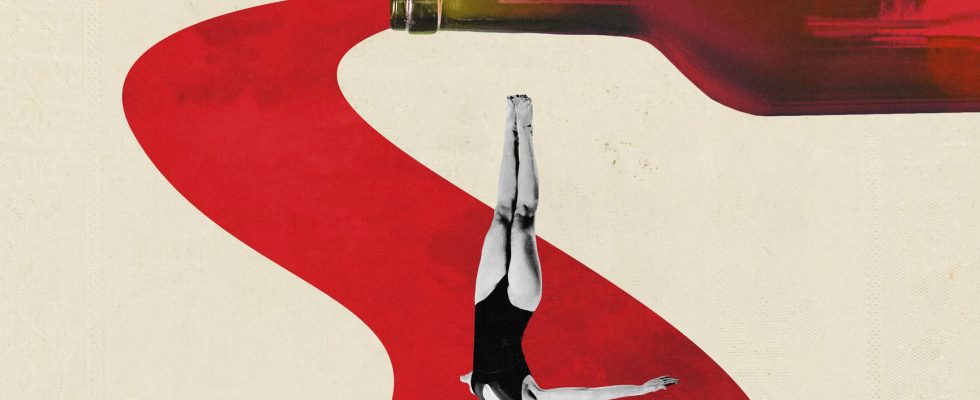

It has become commonplace to speak of sobriety, less common are the discourses on the supreme anti-sobriety, drunkenness. A “sober” word to evoke intoxication, this intoxication which does not have a good press, especially when it concerns the female sex, the ultimate taboo that the years have not been able to erase. Sign of the times (?), three books, signed by three women, address the subject. One, a novel, The drinking woman (Gallimard), by Colette Andris, dates from 1929, the second, drunk girl (Larousse), by Camilla Gallapia, is a comic strip, or, as we say today, a graphic novel, and the third, To our drunkenness (Flammarion), by 33-year-old journalist Alicia Dorey, delivers a few sparkling digressions on the “dive bottle” in the form of a story. Three different genres therefore, but the same paw, devoid of any proselytism, mixing finesse and empathy.

It starts dry for Guita, the heroine of Colette Andris – pseudonym of Pauline Toutey, novelist, (naked) music hall artist and actress between the wars – who swallowed her first sip from a timpani at the age of 8 to get revenge on her parents who refused her a butterfly net. At 16, still blonde and delicate, she gets brutally deflowered by her friend Jacques one day in July, washed down with absinthe and a few glasses of champagne. Friend whom she felt obliged to marry. “Besides, he loved her. It was always that, one out of two happy!” The alert pen, the incisive phrasing, Colette Andris unrolls the years, the lovers (which she wanted, for a time, ardent, authoritarian and brutal) and the glasses.

All is not always rosy, even in those Roaring Twenties, even with this idle and well-to-do Parisian, far from it. A doctor with criminal touching, fruitless calls for help (“Jacques […] save me from my vice. Every day, I drink, and more and more, I understand towards what decline I rush”), a dangerous pitching on a balcony, Jean-Pierre, his redeemer, crushed by a car… But there are also these “evenings when intoxication – a moderate intoxication – brings a hectic gaiety”. a warm welcome.

A “reproved” feminine drunkenness

Lonely despair, the mother of illustrator Camilla Gallapia knew it well. Without a driver’s license and without a job, she languishes in their village house. At least that’s what Camilla imagines in this black and white album which unfolds the family drama from one bubble to another. No cheerfulness here, but a mother lying on the sofa, groggy, “haggard eyes, soft mouth”, at snack time. With this mother whom she adores, and hates when she turns into “the other”, so pathetic, so despicable, she speaks of shame, family silence, friends who are not invited home… Hell, if it hadn’t been for the big sister, with whom she tries to unearth the bottle stashes, and the father, “captain” of the boat. In doing so, Camilla Gallapia is sounding the alarm about the lack of care for children of alcoholics, who are permanently traumatized…

Of the three works mentioned here, that of the editorial manager of the Figaro Wine is certainly the happiest and most carefree, even if the author recalls the permanence of this social rule which requires that “male drunkenness is tolerated, even encouraged, while its female counterpart is condemned”. With humor and in complete relaxation, Alicia Dorey analyzes the mores of our contemporaries and recounts her own practices as a “wine professional” (the morning tastings), but also and above all the “liquid” milestones of her itinerary since the “revelation” at age 25, freeing her “from an endless adolescence”. The journalist lightly aligns the most personal considerations, deals with the links between travel and drunkenness, road trips, the shame of tomorrows, bottles shared with lovers… Not all drunkenness is desirable, Alice Dorey knows, who wants to make the distinction between alcoholism and drunkenness, “a kind of time-expanding machine”. But who does not say – at all – ready to fall into… sobriety.