In 1920, Lucie Cousturier, 43, published Strangers in my house then, five years later, My strangers at home. The story, in two stages, of his meeting, during the Great War, with Senegalese skirmishers posted in a military camp in the south of France. In his house in Fréjus, the neo-impressionist artist, a former student of Signac, gave them voluntary lessons to improve the French language; this is the subject of the first book. The second stems from his trip to French West Africa where the French government commissioned him to examine “the indigenous family environment and especially the role of women”. If Lucie Cousturier is a centerpiece of the exhibition traveling artists, the call of the distant, 1880-1944presented at the Pont-Aven museum until November 5, it is because she is the only one, among the exhibiting designers who worked in the first half of the 20th century, to have dared to openly criticize the colonial system.

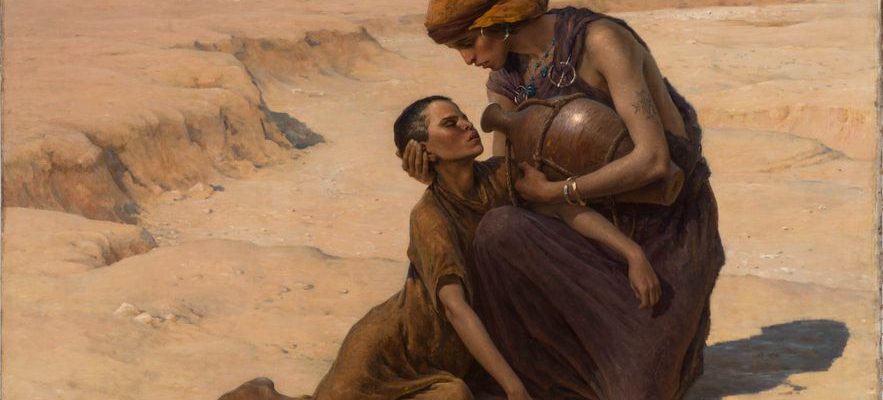

The others (about thirty in total) did not deliver the slightest caricatural or racist rendering in their orientalist creations, but did not, however, question the “civilizing mission” of France at the time. All of them, however, have in common that they belong to those generations of women artists who have long been overlooked by the history of art. “When we have to judge a serious work due to the brain and the hand of a woman, we say: ‘It is painted or sculpted as by a man'”, observes, from 1896, Virginie Demont-Breton. Like her contemporary Marie Caire-Tonoir, the painter from Wissant (Pas-de-Calais) stayed from Tunis to Tangier, passing through Biskra, where the oasis of El Kantara inspired her to create, on her return to France, ofIshmael, a large solemn format on which Hagar gives a drink to her son. The desert is there, even if the models are… Wissant.

Virginie Demont-Breton, “Ishmael”, 1895.

/ © Boulogne-sur-Mer Museum © Xavier Nicostrate

Then it was the boom in colonial tourism during the interwar period that saw women asked to illustrate promotional documents for cruises. The photographer Thérèse Le Prat thus responds to orders from the Compagnie des Couriers Maritimes while simultaneously producing personal portraits from her encounters in the West Indies, Tahiti, Madagascar and even Oceania.

Despite the disparity in their styles, these travelers often seem to have taken a different view of the natives from that of their male counterparts, as Arielle Pélenc, scientific curator of the exhibition, noted during her research: ” They had easier access to the spaces reserved for women in traditional societies, while benefiting, during more adventurous explorations, from the protection of diplomatic and colonial networks.

“Ya-ko-ko-su-ti-ro” mask of tears, Colombia, Tukano people, early 20th century.

/ © Natural History Museum of Lille

In the north of the department, at the abbey of Daoulas, which offers an exhibition until December 3, in partnership with the Brittany museum in Rennes, it is also a question of distant horizons. But this time, it is a question of exploring the relationship of the living to death and the dead, through some 300 objects linked to funeral rituals: the care given to the body, as evidenced by the canopic jars with the head of a falcon or of a jackal from ancient Egypt, containing the viscera of the deceased; mourning outfits and accessories, from the Colombian mask of tears resuming the features of a human face to the black Finistère cape worn until 1945; the last resting place, materialized in Ghana, since the 1960s, by a coffin reflecting an important feature of the life of the deceased; the memory, finally, that we maintain in hair frames or reliquaries. To die, what a story!