Researchers found evidence of a leg amputation in a skeleton determined to belong to a young human.

This finding takes the history of this complex surgery back another 24,000 years.

Archaeologists say the amputated person was cared for by the group he belonged to for years until his death.

Examining the skeleton, Dr. Melandri Vlok said it was “pretty clear” that he had surgery on the leg.

Details of the research have been published in the journal Nature.

When the remains were examined in detail, it was determined that the amputation was done in childhood.

Traces of growth and healing in the leg bone indicate that this person recovered from the surgery and lived for another six to nine years, possibly dying in his late teens or early twenties.

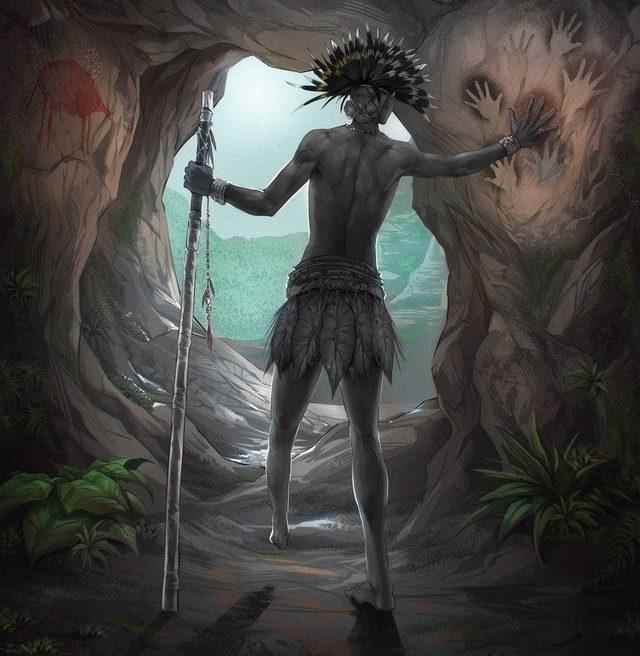

The tomb was excavated in Liang Tebo cave in East Kalimantan region on Indonesia’s island of Borneo, which has some of the oldest rock art in the world.

One of three researchers who found and excavated the tomb, Dr. Griffith University in Australia. Tim Maloney said he was “both excited and horrified” when the bones were revealed:

“We cleaned the debris very carefully and recorded the lower half of the remains. We noticed that the left foot was missing and the remaining bone fragments were also unusual.

“We were excited by the various possibilities that could cause this, including surgery.”

The excavation team later worked at the University of Sydney, Dr. He asked Vlok to examine the remains. “Excitement and sadness go together in such a discovery, because it happened to a person. This person is a child and suffered a lot 31 thousand years ago,” said Vlok.

Dr. Maloney explained that because they found signs of caring for this person during and after his recovery, archaeologists considered it an operation rather than any punishment or ritual.

Durham University archaeologist Professor Charlotte Robertson, who was not involved in the discovery but studied the findings, said they challenged the view that medicine and surgery emerged late in human history.

“This shows us that caring is an inherent part of being human,” Robertson said.

Noting that amputations require extensive knowledge of human anatomy and surgical hygiene and significant technical skills, Robertson made the following assessment:

“Today, when you say amputation, you know that it is a very safe operation. Anesthesia and sterile procedures, bleeding control and painkillers are applied to the person. Then you see that someone had amputated this person 31 thousand years ago and it was successful.”

Dr. Maloney and colleagues are now investigating what types of stone surgical instruments might have been used at that time.

Victoria Gill | BBC Science Correspondent