In dinners in town, from Istanbul to Ankara, an anecdote has met with some success in recent days in Turkey: that of António de Oliveira Salazar’s “false diary”. After 36 years at the head of Portugal, the old dictator, sick, is put aside by his close guard and replaced gently by Marcelo Caetano. But Salazar will never know. Every day for two years, until his death in 1970, his team concocted a special edition of the daily Diario de Noticias without any reference to the new government, in order to make it believe that it is still running the country. “In Turkey, it’s exactly the same, laughs a former journalist, converted into a political adviser in the opposition. Every morning, the sovereign gets up and reads in the press that everything is wonderful. While the leader goes into the wall, and our nation with it.”

Serious doubts about the health of the chef

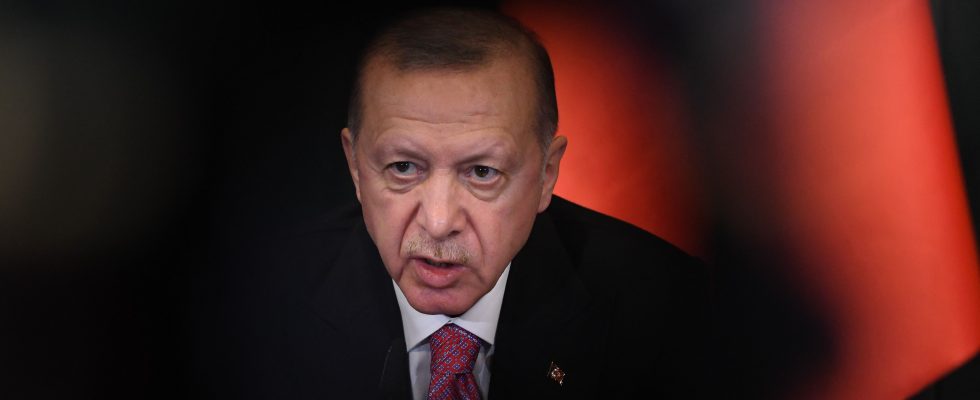

Recep Tayyip Erdogan may have brought the press to heel in Turkey, but it is difficult for the president to escape bad news: 112% inflation, Turkish lira at its lowest level in history, more than 55,000 dead in the earthquakes of February 6, hundreds of thousands of refugees on the roads… And polls that show it, all losing during the presidential election of May 14. For the first time in 20 years, the king wavers.

On April 25, Erdogan even failed live, in the middle of an interview. No image of the scene has filtered, the camera remaining trained on the embarrassed face of the journalist. In the background, only an “oh, wow…” escapes the sudden silence. Back in front of the camera, a few minutes after the incident, the Turkish president appears livid, almost stunned, he who has accustomed his viewers to wearing military fatigues and big black aviator glasses. He explained that he was the victim of a stomach flu and a slight overwork in the countryside. A few days rest and everything will be better, he promised. But the scene has revived old rumors of colon cancer, and above all illustrates the delicate pass crossed by a man long considered all-powerful in Turkey.

“Erdogan leaves really very weak for these elections, believes Bayram Balci, specialist in Turkey and former director of the French Institute of Anatolian Studies. His twenty years in power have created fatigue, weariness, among the people. Omnipresent in the media, concentrating almost all power since his reform of the Constitution in 2017, the trick president finds himself accused of all the ills of modern Turkey. “After the earthquake, everyone was very upset, furious that our government was unable to help those who needed it, says Havva, a teacher from Istanbul. Lately, anger has given way to hope: that radical political and economic change.”

A campaign with Turkish state money

But the old wolf, even injured, does not intend to be swept away by this wind of change. In recent months, Erdogan has deployed all the means of the Turkish state to ensure re-election, either in the first round on May 14 or in the second on May 28. He offered early retirement to two million seniors, doubled the minimum wage and promised the construction of 500,000 new social housing units.

Every day, on campaign, the head of state cuts ribbons and presses buttons to usher in the wonders of “his” new Turkey: the first drone carrier ship, a unit of the country’s first nuclear power plant (built by the Russian company Rosatom), the first Turkish-made tank… The permanent event is Erdogan. “His deep dream is to replace Atatürk in the minds of the Turks, says Ardavan Amir-Aslani, author of Turkey, new caliphate? (Editions l’Archipel, February 2023). He wants to make believe that he is the real father of the nation, by renegotiating the errors of the past, by restoring glory to Turkey, one hundred years after the birth of the Republic.” His reign has already exceeded that of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and he does not intend to stop on the way.

Meanwhile, his adversary, the frail Kemal Kiliçdaroglu, had to cancel his meetings under threat. Not enough to push back the opposition, cautious but united for the first time in twenty years: the six main political parties, from the left to the nationalist right, have rallied in a grand coalition, behind a single candidate.

“Since the start of the reign of the AKP (Justice and Development Party), the opposition has never been so able to win, raises Berk Esen, professor of political science at Sabanci University, in Istanbul. The moment is crucial, because if it fails, the opposition will lose hope, like all opponents of the ruling party. Many secular Turks will continue to leave the country, weakening the opposition even more and making even more difficult a change of regime in the years to come.

At 69, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has never hidden his authoritarian appetite. In 1996, then mayor of Istanbul, he pronounced this sentence, which has since become a doctrine for his supporters: “Democracy is like a tram. Once you get to the terminus, you get off.” For twenty years, he has applied his motto to the letter. And everyone wonders at which tram stop Turkey is today.