Emily is not in Paris but should land in the Allier in 2028. At least that’s theobjective announced last October by Imerys, world leader in mineral specialties, which wishes to operate a lithium mine on the Beauvoir site, in Echassières. The Emili project is part of the European desire, also brandished by France, to secure the territory’s supplies of strategic resources. Lithium is part of this restricted circle, since this alkaline white metal is used, among other things, in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicles.

But lithium needs, element deemed crucial by the European Commission and erected by some in “white gold”, will explode in the years to come under the impetus of the ecological transition and the electrification, in particular, of the automotive sector. It will take about 35 times more in 2050 than today, according to a study published in April 2022 by the University of Louvain (Belgium). To stick to the fixed climate objectives, “we will have, in the next 30 years, to extract as much as since antiquity until our days”, illustrates Marieke Van Lichtervelde, researcher at the laboratory Geosciences Environment Toulouse (GET). Lithium production is currently concentrated in a few countries (Australia, Argentina, Chile, China), hence the interest, a question of sovereignty, of relocating production.

“If you want to make a transition for 2050, you have to open mines”

Because the observation made by Sébastien Pinet, professor at the Faculty of Geosciences and the Environment of the University of Lausanne (Switzerland), is clear. “Commodity demands are great and have long been underestimated and neglected. If you want to make an energy transition for 2050, you have to open mines. But right now, mines are the devil, and rightly so in many cases,” he says. The image of the sector is hardly brilliant and the projects announced in Portugal, Serbia or the Allier have generated criticism and dissatisfaction from the local population and environmental organizations, which warn of the environmental impact of such sites.

“We are never opposed in principle, defends Antoine Gatet, vice-president of France nature environment (FNE). But we are not going to accept mining projects for false pretexts.” In the case of Imerys in Allier, where the group is counting on the production of nearly 700,000 electric vehicle batteries per year, the lawyer deplores the lack of consultation upstream and the absence of information on environmental procedures. . Above all, he regrets the absence of a broader debate on modes of mobility, sobriety and advance planning. “We open wide the floodgates of private industrial projects. And mining is the worst industry of all. France has memory: a clean mine, we don’t know how to do it,” he recalls.

With us or with others?

“We are leaving the era of oil to enter that of metals. We know what the first has generated in terms of negative impacts, but people are not aware of what the second represents”, remarks Marieke Van Lichtervelde. As always, there is the question of acceptability. How far do we allow ourselves to go to do without fossil fuels and decarbonize society? “We have to take a certain number of the faults associated with mines here. Explain to the populations the needs, show that we are doing everything to minimize the environmental impacts – even if there will always be some, notes Sébastien Pilet. But if we stay in the current approach, we are going to green Europe to the detriment of other regions of the world where the conditions for extraction and production will be less good. Whereas we could control a good part of the system.” Antoine Gatet, he does not believe “in independence throughout the sector. This is not possible for current use and consumption.”

“The opposition to the mine should not be made on the point of environmental impacts, because they will be less here, continues Marieke Van Lichtervelde, member of the Political Ecology Workshop (Atecopol). The real problem is: that are we going to make this lithium?” Implied: it must not end up in SUVs or electric yachts. The geologist stresses the need to discuss uses. “Sobriety, you have to go all out, abounds Sébastien Pilet. However, we remain in a world where energy is fundamental. We therefore need a general awareness of critical raw materials.”

Infographics

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

“No one has an interest in bringing this issue forward”

It begins to emerge in the unstable geopolitical context. But brakes persist, analyzes the professor at the University of Lausanne. “Nobody currently has an interest in putting this question forward, in making it a priority issue. they say they want to open mines.” The French executive, which launched the French Observatory of Mineral Resources for Industrial Sectors (Ofremi) at the end of November, was however delighted with the Emili project which, according to Minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher, will “d’ ensure our energy and industrial independence”.

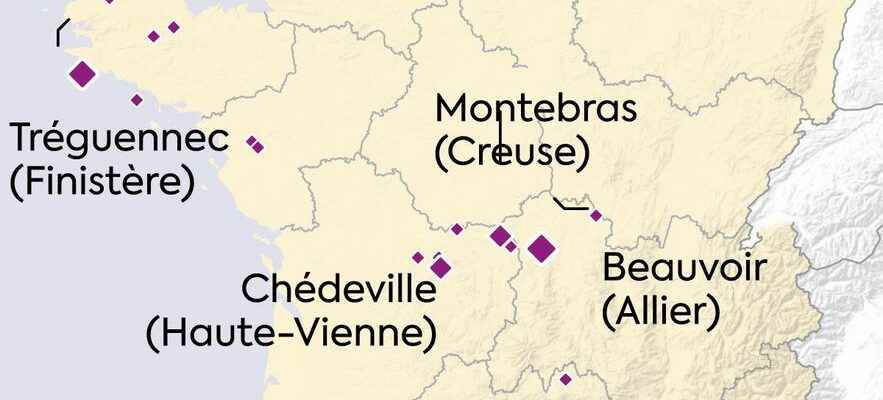

The Echassières mine could only be the first of its kind. In 2021, the Geological and Mining Research Bureau (BRGM) established an atlas of critical and strategic substances contained in metropolitan soils. Other lithium deposits – medium or large – have been identified: Montebras (Creuse), Tréguennec (Finistère), Chédeville (Haute-Vienne)… But this is only a single material, the reserves of which exist In France. For other metals that are not listed, or in very small quantities, on the national territory, the dilemma is no longer: it will be necessary to rely on other countries, regardless of the conditions of extraction and production.