With its 15 meters height, its 6,000 meters of intertwined prisms and its 1,400 glass bars, this is an improbable tour de force. Thoughts, the title of this extraordinary work, required eight tons of fragile material and 12,000 hours of manual work in the workshop of Emmanuel Barrois, a former SNCF warehouse near Brioude, in Haute-Loire, the region origin of this 59-year-old Auvergne. It is also a meaningful project, which questions the relationship to construction and to man in an increasingly virtual post-Covid world. To the search for the absolute is added the praise of complexity. Two of the mantras of the master glassmaker with an atypical career.

Glass actually entered the life of the trained agronomist by chance, who first worked in humanitarian aid in Africa and the Middle East, before being promoted to press photographer thanks to personal photos taken in Afghanistan which are published. During a report for World, he met a glassmaker and, overnight, became an apprentice under his direction, fascinated as he was by “light, color, solitary hand-to-hand combat with the material”. At the beginning of the 1990s, Barrois found his calling: glass and its infinite potential.

In the heart of the Jardin du Palais-Royal, a 15 meter high scaffolding.

/ © Atelier Barrois

“More than a job as a heritage technician, I wanted to participate in the advent of the architecture of my time, as the 13th century glassmakers did in their time,” he explains, he who began his third life as a stained glass artist for historical monuments. Then he crossed paths with Claude Parent, the champion of the inclined plane breaking with the modernist codes of his time, who determined him to embrace contemporary creation. Since then, Barrois has produced a series of daring achievements for the cream of architects: the white scale facade of the Frac de Marseille designed by Kengo Kuma, that of the Carrousel du Louvre designed by Jean-Michel Wilmotte, the covering of the Peking Opera designed by Paul Andreu, or the Canopée des Halles with Patrick Berger.

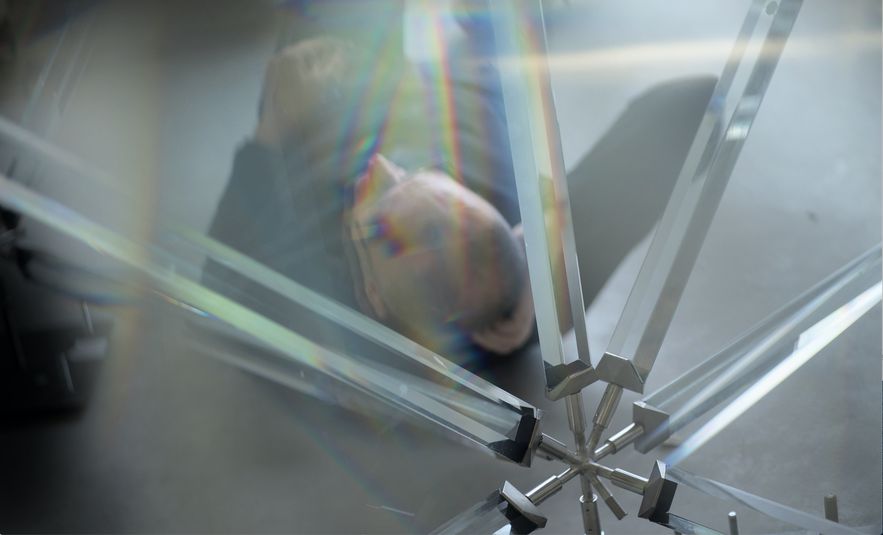

His Thoughts are today deployed under the Paris sky, in the heart of the Jardin du Palais-Royal, placed in the central fountain, and visible until November 15. The glass designer had the idea during the Notre-Dame fire, torn by the unthinkable by the desire to create a work for the general public as an ode to the builders. Remembering an attraction using the kaleidoscope, seen as a child at the Trône fair, he foresees the form that this giant mikado will take, where the play of reflections will take first place. “For me, glass is solid light,” he claims, not without mentioning the abysmal challenge that this undertaking, much more complex than it seemed to be at the start, represented. There were the inevitable brakes of Covid, but also and above all the technical questions to which no one had yet answered, this type of project being completely new: “With this installation, we have pushed the limits of what has already been done “.

A complex achievement combining artistic craftsmanship and cutting-edge engineering.

/ © Atelier Barrois

“We” are, around him, the dozen craftsmen who enamell, leaf, tint or polish the glass until transforming it, in the Brioude workshop. And it is also the involvement of external players such as the Bollinger-Grohmann design office, for engineering, or Arte Factory Lab, for computer-generated images. Because the strength of this itinerant structure (it will then move to Rome then to Japan), which has been the subject of detailed studies to resist bad weather, lies above all in hybridity, when combining know-how ancestral manual work and industrial processes makes it possible to create innovative projects that neither industry nor crafts could implement alone.