You will also be interested

[EN VIDÉO] A billion years summarized in 40 seconds: plate tectonics Researchers have modeled the movements of tectonic plates over the past billion years.

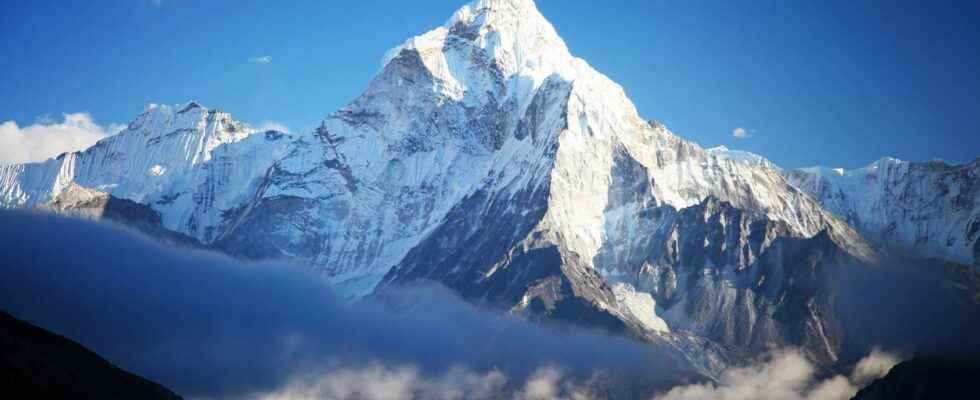

Among the manifestations of tectonic plates and the formidable migration of continents over time, the collision chains are certainly the most emblematic and the most visible in the landscape. The Himalayas, home to the highest peak in the world, are the result of the collision of the Indian continent with Asia. This event represents one of the major tectonic episodes of “recent” geological history. Because 200 million years ago, the situation was very different from that of today.

The analysis of movements continents, by through magnetic anomalies recorded by the ocean floor, teaches us that in the Triassic, India was located much further south, within the supercontinent Gondwana, which then began to fragment. Between the north of the Indian block and the Eurasian continent is a huge ocean that has now disappeared: the ocean Tethys.

The Himalayas, the result of India’s mad dash north

It is the double action of the opening of the current South-West Indian Ocean and the closing of the Tethys which will lead to the rapid migration of India towards the north. Fast is still an understatement. Because India will thus move to a speed quite exceptional at 20 cm/year! A mad race which brings him very quickly in contact with Asia. The violent collision that will lift the whole region and give birth to the Himalayas but more generally to the Hindu Kush-Himalaya area will thus begin about 60 million years ago.

For a long time, scientists have been interested to the engines of this dazzling continental migration. Among the proposed models, that of a double subduction. A hypothesis that has just been supported by a recent study, published in Science Advances.

Not one, but two successive subduction planes

The team of Chinese researchers has indeed highlighted the presence, in the coat upper located under the Myanmar region in the eastern range, remains of ancient slab. A slab represents the part of the plate which has entered into subduction, that is to say which has passed under the overlapping plate.

By accurately imaging the upper mantle in this region, thanks to seismic waves and the deployment of a new network of seismic stations, scientists were able to observe for the first time the presence of not one, but two parallel subduction planes, plunging into the depths of the mantle at the level of the suture of the ancient Tethys ocean.

The westernmost slab, which is characterized by a high velocity zone compared to that of the mantle rocks, was already identified by previous studies and represents the currently active subduction system. For India’s indentation into Eurasia is still ongoing, even though the speed of convergence is much lower than it was 60 million years ago.

But the Chinese researchers have just identified a second plane plunging towards the east, located in front of the first. The associated velocity anomaly is observable up to 300 km depth. For scientists, this is the signature of an ancient slab, now inactive, which would have participated in the closing of the Tethys ocean about 40 million years ago.

This new discovery naturally has implications for the tectonic models hitherto used to illustrate the convergence of India and Eurasia. In particular, it helps to explain the rapid migration from India to the north.

The remote village of Lingshed in Zanskar Ladakh is the region of India with the highest average altitude. Most of it is located at more than 3,000 meters above sea level. The neighboring Zanskar corresponds, with an altitude exceeding 4,000 meters, to the highest populated valley of the Himalayas. In these regions, the rhythm of life is organized around work in the fields. Elaborated and improved from generation to generation, the irrigation canals make it possible to convey water to the different cultures. Barley, wheat and peas are the staple food for these high altitude peoples. This mosaic of cultivated fields makes each village — here that of Lingshed, inhabited for almost a thousand years — an oasis of greenery during the three summer months. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Likir Monastery a jewel of Buddhism The monastery of Likir Gompa was built in 1065. It stands more than 3,500 meters above sea level, about fifty kilometers west of the capital of Ladakh. It houses a fine collection of Thangkas, ancient manuscripts and traditional costumes. And it offers those who venture there, a breathtaking view of the Nubra Valley. There is also a magnificent statue of the golden Meutraya Buddha, the oldest golden Buddha in the region. A visit to the monastery of Likir is also worth the special spiritual atmosphere that reigns there. Every day, the monks alternate between prayers and daily tasks necessary for the proper functioning of it. Here, a monk serves salty tea to Lamas during the Dasmotches Buddhist festival. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Holder: a risky profession The job of porters is to accompany foreign climbers in their quest for the Himalayas. Delivering their food and equipment. Traditionally enduring local mountaineers, today they are often replaced by inexperienced teenagers who risk their lives… to earn it. Here, the porters Lobsang and Stanzin. They are experienced. They live in Pishu. They leave Zanskar by the Chadar, the frozen river, to reach the city of Leh 100 km away. It has been snowing non-stop since last night and this makes the journey dangerous. In addition to causing avalanches, snow masks the state of the ice. It becomes essential for Stanzin to probe her with his staff at each step, while Lobsang sings his rosary while reciting prayers. You never venture alone on the frozen river. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Young Angmo already sees himself as a doctor Angmo, seen here in the foreground, is only 13 years old. He studied in Leh, the capital of Ladakh perched 3,500 meters above sea level. His dream: to become a doctor! While waiting to obtain his diploma, he participates in the chores of the village of Lingshed. And he goes up here, in his back, a beam of 14 kg. The role of the men is to transport the wood on the frozen river to the plumb of the village. The women then take over to carry the boards and beams that will be used to build the school and repair the nunnery. One hundred and fifty volunteers are mobilizing for the community. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Namgyal, always laughing He still resounds with Namgyal’s laughter in the gorges of Chadar. This father is one of the 150 men who carried the wood over the frozen river to bring it closer to the village of Lingshed where it was expected. After several hours pulling the loads on the ice, a short break allows everyone to eat around a salted butter tea. Tsampa, roasted barley flour, is the staple food of the Zanskarpas. It is also an integral part of Tibetan Buddhist rituals. To amuse the photographer, Namgyal sprinkled it on his nose. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved.

In the tradition of Zanskar: the mix of generations Three generations live under the same roof. Chomdan, right, lives in the home of his wife Dolma with their four children and his stepfather, Grandma Tsering. Mémé is a script known to monasteries for its calligraphic quality. He makes his own paper with herbs. He makes his ink with soot and sometimes even with gold leaf for certain sacred texts. It was also he who wove this traditional dress, the goncha, with goat and yak wool. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

In Zanskar, life is modernizing In Dolma’s family, Mémé Tsering died. Chomdan, the father of the family, goes away several months a year to look for work. In Leh, he is hired as a guide or porter by trekkers. With his salary, he finances part of the schooling of two of his sons. He also brings the family clothes and foodstuffs from the city. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Two women, two cultures… two friends Her face marked by a rustic life, tanned by the sun and the altitude, Abi Chumik — the source’s grandmother — was unable to have a child. It is therefore she who, despite her age, takes her herd every summer to the remote sheepfolds of the village to allow her husband to cultivate their few plots of land without the risk of seeing their crops trampled and eaten. Véronique joined Abi Chumik a day’s walk from Zangla, in his doksa, a stone shelter. Two women, two generations, two destinies, two cultures, one from the Himalayas, the other from the Alps, linked by several years of friendship. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Newcomers to the village sheepfold In Zanskar, in the heart of the Himalayas, the villagers live mainly from herding herds of yaks, goats and sheep. The photographer takes us here to the heart of a sheepfold. Every evening, the child shepherds bring the herds back to the village for milking. With the milk, the women make butter, cheese and yogurt. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Carriers of wood, always dangerous paths Sonam lives in the small village of Skyumpata. Here, no more than twenty houses. Every winter, with two of his neighbours, they venture on the frozen river to climb uninhabited valleys with the trunks of hundred-year-old trees that will serve as beams for their houses. Several winters will be necessary to bring back enough wood.

Indian army boots to replace traditional footwear In the heart of the Himalayas, in the regions of Ladakh and Zanskar, second-hand Indian army boots have replaced traditional shoes made of yak leather and goat hair. These military boots are bought on the market in Leh, the largest city in Ladakh, where the Zanskarpas also find second-hand sleeping bags, hats, gaiters and many other materials. © Erik Lapied, all rights reserved

Interested in what you just read?