ASSEMBLED DISSOLUTION. The opposition dispossessed Emmanuel Macron of his absolute majority, raising fears of an institutional paralysis calling into question his ability to govern. Faced with a fragmented political class, could dissolution become the solution?

It is an electoral setback that could well turn into paralysis. The formation of the presidential camp Together! came up against the degagisme during the second round of the legislative elections. Far from the 308 deputies sent to the National Assembly in 2017, LREM and its allies will have to settle for 246 seats this time. In question, the strong electoral mobilization around the new left-wing coalition, the Nupes, which won 142 places, but also a historic breakthrough of the RN, with 89 elected. It will also be necessary to deal with a surviving right which, if it goes from 112 deputies to 65, has saved the furniture. In this situation, Emmanuel Macron and his relative majority will be forced to negotiate alliances and make compromises for each reform project. The blockages are expected to be numerous, the opposition leaders, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen, having every intention of making their protesting voices heard. More worrying still, the feverishness of a government weakened by the electoral rout of three of its ministers in the legislative elections (who will therefore have to pack up) and by the uncertain future of a Prime Minister whose legitimacy is (almost) unanimously challenged by the opposition.

How to govern in these conditions? At the top of the state, no option is excluded, explains The world. The government could decide to build a majority “on a case-by-case basis” for each file, by trying to bring together the 289 deputies needed to vote on laws (289 being the threshold for an absolute majority). But the simplest would remain the elaboration of a legislative agreement, or even a government pact, with another group. In this case, one would expect Emmanuel Macron to turn to the Republicans, a party with which he has fewer points of difference than with the RN or Nupes. But for now, the possibility of a rapprochement has been ruled out by the right-wing party. On June 21, Christian Jacob, president of the party, reiterated on France Inter the will of his group to appear as a “firm opposition”, even affirming: “The answer will not be in tricks and shenanigans”. Together! could therefore find themselves very isolated the day after this electoral period… Unless they pursue it by calling the French people to the polls by dissolving the National Assembly.

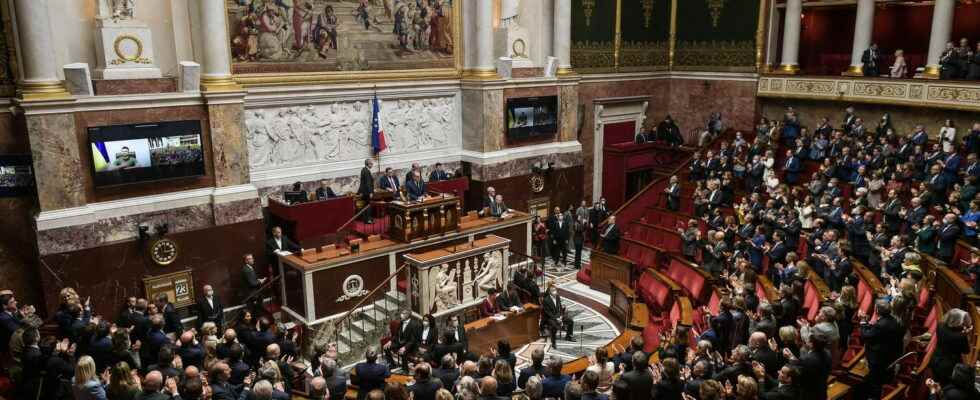

Dissolving the Assembly could end up becoming an option to get out of the institutional crisis that currently threatens the country. After the legislative slap will come the time of slowing down, even of immobility, when the new government will want to pass its first laws. Indeed, how to find a point of agreement on issues as divisive as pension reform or ecological planning? The reforming capacity of the government risks being largely hampered by an impossibility of finding a compromise with the forces of the opposition. In fact, in Parliament, the relative majority of Emmanuel Macron will have difficulty in forging alliances. But this will not be less true for the other forces in power, starting with the Nupes, which must already manage internal differences, the PS and LFI having very distant positions on many subjects. On the side of the RN, if the party seems united internally, the logic of the Republican front could prevent a rapprochement with other parties. Thus, a dissolution of the National Assembly would allow the Head of State to cut short the talks which promise to be laborious, or even simply to ensure that he can govern without blockage by aiming to win, this time, an absolute majority. Provided for in Article 12 of the Constitution, it can be pronounced by the President of the Republic “after consulting the Prime Minister and the Presidents” of the National Assembly and the Senate. This decision would lead to a new call of voters to the polls.

The only truly binding rules governing the dissolution of the Assembly relate to time limits. The Head of State must wait a year between two dissolutions. But in the present case, Emmanuel Macron will not have to wait because, as specified The world, the time limit to be observed after a legislative election is not specified in the law and can be reduced to nil according to constitutional interpretation. Once the dissolution has been pronounced, the convening of new legislative elections should take place “twenty days at least and forty days at most after the dissolution”.

Is the hypothesis of a dissolution of the National Assembly by Emmanuel Macron in the event of re-election really possible? Factually, yes. On the other hand, politically, the operation promises to be more delicate. Both for the image sent back to the parliamentarians with whom he will have to deal for the next five years and to public opinion, he to whom the “Jupiterian” image already sticks. But the main risk lies in the outcome of these new elections. In the event of further disappointment (or even defeat) at the polls, it would be difficult for his side to recover. “If the result (of the vote) is the same, it would be a terrible political setback”, explained to CheckNews the doctor of public law Aïda Manouguian.

And how can you be sure it’s the right strategy? Nothing says that this dissolution would be conclusive for the presidential camp. According to Bruno Cautrès, political scientist and researcher at the CNRS, it is a “double-edged sword”, as he explained to our colleagues from France Info. “Given the half-hearted popularity of the two heads of the executive, this could be a gift to Jean-Luc Mélenchon”, he warned, referring to the significantly lower scores of the head of state at the presidential election and the Prime Minister whose future at Matignon hangs by a thread. Not to mention the growing electoral base of the two major opposing camps, namely the Nupes and the RN, which have clearly progressed at the polls in the last elections.

Above all, an immediate dissolution could seem hasty, even disconnected from democratic reality. While abstention reached a very high level (53.77% during this second round), voters could have the feeling that the President is ignoring their voices. “It is not interesting for the president to dissolve the Assembly immediately”, explained to France Info professor of public law at the University of Lille Jean-Philippe Derosier. “The poll has just taken place. To dissolve immediately is to refuse to recognize the voters’ choice.” According to him, opting for this radical choice “before the government encounters difficulties” in its governance would be “an extremely risky strategy politically”. On April 17, long before all these events, Emmanuel Macron assured that he would not consider such an eventuality: “I have too much respect for democratic meetings to shake them up or give the feeling, in a way, of playing with them. ” But today, the situation is very different.

The presidents who have allowed themselves to be tempted by a dissolution have not all met the same fate. Twice, it was used to respond to a national crisis: it was a success for Charles de Gaulle, who extricated himself from particularly delicate situations by obtaining a solid majority in 1962 and 1968. But, out of the three which were intended to consolidate (even to build) the majority of the presidential camp in the Assembly, one of them was a marked failure. One thinks here of Jacques Chirac’s failed electoral bet in 1997, who dissolved Parliament with the aim of obtaining a larger majority and thus avoiding any ounce of political blockage during the passing of laws. He finally lost everything when the Socialists ousted him at the ballot box, propelling Lionel Jospin to the post of Prime Minister and forcing Jacques Chirac to live together. It remains to be seen whether, in the case of Emmanuel Macron, a possible dissolution would be justified by parliamentary paralysis or by the need to overcome political divisions to overcome a crisis. Or if it would appear as a desperate attempt to oust the opposition.