Cécile Asanuma-Brice co-directs the Mitate-Lab, an international CNRS research project that studies the situation following the Fukushima disaster. While the site’s wastewater discharges into the Pacific Ocean fuel tensions, she returns for L’Express to the fractures of the Japanese population.

The Express: The discharge of waste water from Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean continues to create turmoil, feeding in particular the tensions with China. How is the Japanese population reacting to the situation?

Cecile Asanuma-Brice : She is really divided on the issue. Half were convinced by the authorities of the non-dangerousness of the operation. For these people in favor of reviving the nuclear industry, it is a necessary evil for the dismantling of the plant, without which the reconstruction and economic recovery of the region will be difficult. And in this context, the discontent of China came to revive the nationalist verve of the Japanese.

However, the other half of the population is still strongly opposed to the release of the waters in the Pacific, with a feeling of anger all the more vivid as the date chosen was officially announced two days before it was to take effect. Also, the fishermen felt betrayed by what they believed to be a discussion with the Prime Minister, when the decision had already been taken. The inhabitants of the region and other civil associations are currently mobilizing to express their opposition. Some have even planned to sue Tepco (Editor’s note: the operator of the Fukushima nuclear power plant) and the Japanese government. A complaint should be filed to this effect with the Fukushima District Court on Friday, September 8.

Are nuclear and the tritium issue the subject of disinformation in Japan, thus throwing oil on the fire?

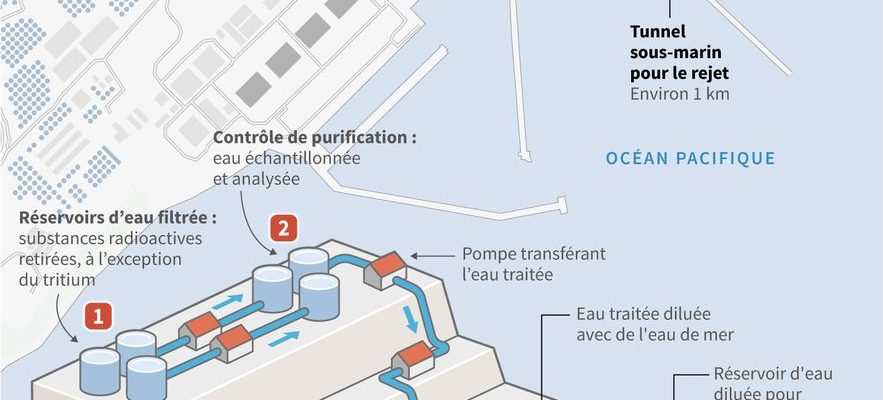

Difficult to answer this question. It seems to me that the information about nuclear in Japan is that which one finds in any nuclearized country, with the significant tensions between the defenders and the opponents. That said, the releases of tritiated water from the Fukushima plant are not comparable to those from French plants because it is liquid that has been in direct contact with cores that have melted, which is not the case. in an undamaged plant. As a result, besides tritium, which is present in much greater quantities than under normal discharge circumstances, there are still traces of 39 other nuclides in the waters that Japan has started to discharge.

Fukushima water discharge

© / afp.com/Nicholas SHEARMAN

Do the scientists, whose opinion should serve as a guide, agree on the way forward?

Alas no. There are controversies, especially on the part of American oceanographers, including the National Association of Marine Laboratories, which brings together more than a hundred oceanographic laboratories. Some researchers, specialists in marine issues and sometimes in the effects of radioactivity in the marine environment, such as Ken Buesseler, published a statement opposing the waste water discharge plan. There is no consensus among scientists and a significant number of them consider that it would have been more reasonable to wait for the level of radioactivity of tritium to decrease naturally before releasing it into the sea.

The Japanese government announced last year that it was considering building new nuclear reactors. Will he find enough support for such a project?

The government is trying to win the support of the people by trying to convince them in three ways. First of all, there is the military argument, motivated by the tensions in the area which are increasing with China and North Korea. It is not officially expressed but appears in halftone. Then there is the question of energy security revived by the Russian-Ukrainian war. Finally, he warns against the production of CO2 generated by the other energies used by Japan, such as gas, fuel oil and coal.

But this argument runs into headwinds. There was a huge investment in the photovoltaic sector after Fukushima, which allowed the country to ensure a significant base of its energy production via renewable energies. This weakens the CO2 argument for some Japanese. Moreover, nuclear power never had a good press in the countries of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and it was through propaganda that the post-war Japanese-American authorities imposed nuclear power on the people, who was strongly against it. Anti-nuclear movements resumed with fervor after Fukushima. Today, the polls show a 50/50 division of the population between pro and anti-nuclear, despite a very important communication campaign on the part of the government. As we can see, the game is far from won.