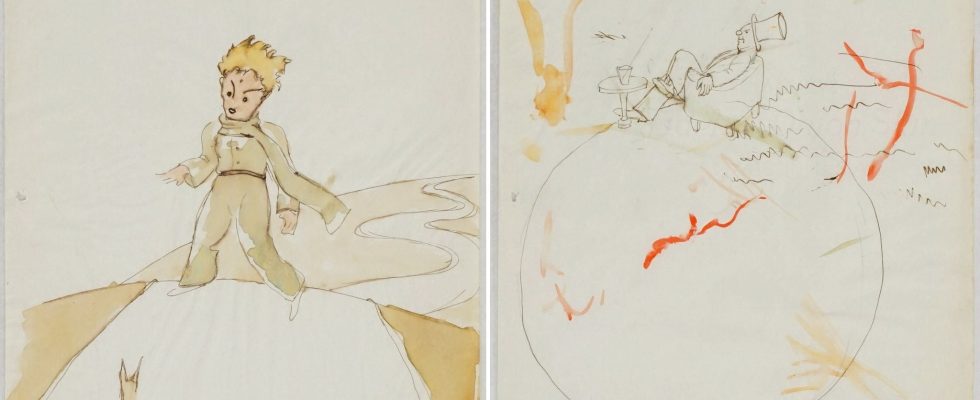

Raphaël Enthoven opened hostilities on Europe 1 in 2017, before doing it again in Point in 2018: finding “no interest in all these interchangeable pages”, he lost his mind The little Prince, a “consensual salad [pleine de] truisms”. In 2023, literary critic Elisabeth Philippe followed suit in The Obs, making fun of this “nice and sweet little tale” which, according to her, aligns with the “mantras of personal development”. We know that, with 550 languages and dialects on the clock, The little Prince is the second most translated book in the world after the Bible. We know less that the work of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry will enter the public domain at the end of 2031. No need to worry for his fifteen rights holders: the Little Prince, a universal character, is also ( especially?) has become a global brand which, between films, exhibitions and derivative products, generates 80% of the revenue linked to their great-uncle. The end of copyright will almost be a non-event. Proof that business has taken precedence over literature?

A few months before the celebration of the 80th anniversary of the death of Saint-Exupéry (disappeared at sea off the coast of Marseille, with his plane, during a scouting mission, July 31, 1944), two essays pay tribute to his memory. In Saint-Exupéry. Wind in the heart, a tight book like Pierre Michon, the academic and author Nathalie Prince (predestined name!) has fun telling the writer’s life by using the structure of the Little Prince. In Saint-Exupéry. A little prince in exile, the journalist and writer Jean-Claude Perrier focuses on his American years, from 1940 to 1943, those during which he notably wrote The little Prince. Nathalie Prince like Jean-Claude Perrier see in “Saint-Ex” a tormented man, very far from the kitsch image of a slightly silly children’s author that his adversaries would like to stick to him for eternity.

Remember that, in the daredevil genre, Saint-Exupéry would have made Sylvain Tesson pass for Eric Reinhardt. An Aéropostale pilot, he was an extremely adventurous aviator, whose crashes are countless – the most famous: that in the Libyan desert, in 1935; the one in Guatemala, in 1938, which will leave him with lifelong aftereffects and pain. When he’s not borrowing Gaston Gallimard’s Bugatti to drive wildly, he writes. At Gallimard, it is published by André Gide himself. He won the Femina prize in 1931 for Night flight, then the grand novel prize of the French Academy in 1939 for Land of men. He collaborates in parallel with the Paris-Soir of Pierre Lazareff, like Joseph Kessel, whose friend he is. Unhappily married to Consuelo, he had numerous affairs and drowned himself in alcohol, like Fitzgerald – they also died at the same age, at 44. What to add? That he was adored by both Jean Renoir, Orson Welles and Martin Heidegger and that he fell out with André Breton, which is always proof of intelligence. It’s difficult, after that, to see in Saint-Exupéry the simpleton described by his enemies…

“Some jealousies”

While another aviator, Romain Gary, is entitled to all the praise, why is Saint-Exupéry so underestimated? According to Jean-Claude Perrier, there are several reasons: “From his first book, published by the largest French publisher, and dubbed by Gide, a true guru in his time, Saint-Exupéry was both respected by his peers, awarded, and read by the general public. Enough to arouse some jealousy, already during his lifetime. Then, during the war, some strong minds criticized him, absolutely wrongly, for a possible recovery by Vichy, as well as for not not to have been a Gaullist – a subject more complex than it seems, as I show in my book… Saint-Exupéry, read by millions of people around the world, is paradoxically not mainstream : it is not the subject of university theses or scholarly publications. It’s not fashionable. Let us hope that the commemorations of the 80th anniversary of his death for France will change the situation. That said, you cite the case of Gary, and it seems to me that you are wrong: Gary suffered the martyrdom of not being recognized enough as a writer, snubbed by the literary world. He may have committed suicide because of this. It is more in favor today, but not with the supposed intelligentsia.”

On this last point, Nathalie Prince sends us back to our worldly affairs: “I admit that I can’t really answer: I don’t know enough snobs who don’t cite Saint-Ex, and even fewer snobs who cite Gary too much! All the Both were passable students. Both had writing in their blood. Both served in the war and were heroes. Both put a lot of themselves into their books. Both both looked death in the face, but with different methods. Both had the honors of the Pléiade, statues named after them… I will just say that Saint-Exupéry lived less long – that can count, too. One died in 1980, the other eighty years ago.”

And Nathalie Prince goes against our thesis and defends the idea that the trade around the character of the Little Prince serves Saint-Exupéry: “I don’t believe that he has been eclipsed. We are clearly not in the case of James Matthew Barrie, who no one remembers wrote Peter Pan. Saint-Exupéry still has his place in people’s minds and hearts, even if his Little Prince seems to steal the show. With the countless products derived from his work, which are the markers of our society, we are far from the values defended by Saint-Exupéry. I do not position myself on the merits or the ill-foundedness of marketing; we are in this society as actors, as consumers and requesters. But marketing, and this is where it interests me, does not erase the written word. For having devoted a large part of my research work to children’s literature [La Littérature de jeunesse, Armand Colin, 2021], I will say that, when the child handles a figurine of the Little Prince or puts a yellow coin in his piggy bank in the shape of a red plane, he begins to enter the book. It is a vast transmedia and transcultural process that must not be overlooked. It’s a form of first encounter with the literary world.”

When we ask our two specialists which book by Saint-Exupéry we should reread, they agree on Citadel. Jean-Claude Perrier sees it as “a rich posthumous book, of great depth, even if it is not the book as Saint-Exupéry himself would have published it”. Nathalie Prince is more forthcoming: “Citadel reminds me of the great fragmentary texts of German romanticism. It is a book that could not be finished, or that certainly should not be finished. A book that wants to give meaning to human life, that shows the importance of connections, a book about human vulnerability. A book shared between the temptation of lightness and that of heaviness, between urgency and patience, between the beauty of solitude and the love of men, between resemblance and difference. A bedside book, which allows us to answer this question which literally haunted Saint-Exupéry: why are there so many men on earth… and so little humanity?” A good idea for a gift to give to Raphaël Enthoven, to reconcile him with Saint-Exupéry.

Saint-Exupéry. Wind in the heart, by Nathalie Prince. Calype, 109 p., €11.90.

Saint-Exupéry. A little prince in exile, by Jean-Claude Perrier. Plon, 162 p., €19.

.