Two onlookers sitting on the same bench, on the Ile de la Cité, in Paris. They avoid looking at each other, so that a walker could not guess that he is passing in front of… a job interview at the DGSI, the French internal intelligence service. In this spring of 2018, Lise (the first name has been changed) is finishing a degree in Arabic at the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (Inalco), she is the best in her class. One of her professors asked her if she could consider performing simultaneous translations for a government department.

A few weeks later, a man, vague about his exact job, called him on a “private number”, gave him an appointment. And here she is answering questions while trying not to plant her eyes in those of her interlocutor, discretion obliges. “Apart from the location, it was a classic interview. The recruiter asked me where my attraction to this region came from, if working for the State interested me, if I could recognize this or that accent”, remembers this former student, not the only one of her promotion to have been asked to translate listenings.

Finally, Lise will not be recruited by the French secret service. Despite his very French name, part of his family lives in a foreign country, which constitutes a disqualifying “vulnerability” in the eyes of the police. Every year, a handful of graduates of “Langues O'”, as the establishment is nicknamed, are approached by French intelligence. The great Parisian school, founded in 1795, has the reputation of training the best specialists in oriental languages. Great ambassadors, such as Maurice Gourdault-Montagne (Hindi and Urdu) or Jean-David Levitte (Chinese and Indonesian) came from it, as well as a multitude of secret agents.

“To work in intelligence, mastering an oriental language is obviously a plus. It saves the service from having to train at great expense internally”, confirms Alain Chouet, former head of service at the General Directorate of External Security ( DGSE)… and former Inalco graduate, in Arabic. In 2021 and 2022, the DGSE and then the DGSI came to present the “career opportunities” within them, in the presence of the public relations officer of the foreign service or the head of the translators section of the counterintelligence directorate.

Inalco, nest of spies?

Quite recently, Langues O’ was concerned with another story of influence. One of his lecturers in Ukrainian, also president of an NGO supporting Ukraine, was refused French nationality because of a white note from the DGSI, revealed the specialized media Intelligence Online in January 2023, which the Express confirms. French counter-spies reproached him for his links with the Ukrainian secret services in France. “Inalco is a reserve from which to draw translators, but also an often infiltrated structure. Security takes precedence”, comments a former French intelligence officer. Inalco, nest of spies? It wouldn’t be so surprising. Since its foundation, under the French Revolution, with the aim of supporting foreign policy and trade, the Grande Ecole has established itself as an international reference. Every year, it welcomes 8,000 students and offers training in more than 100 languages, an offer unequaled in the world. A tenacious rumor recounts the influence attributed to it: in 2001, after the attacks of September 11, the FBI contacted Langues O’ to seek the assistance of specialists in Pashto, the language of the Taliban.

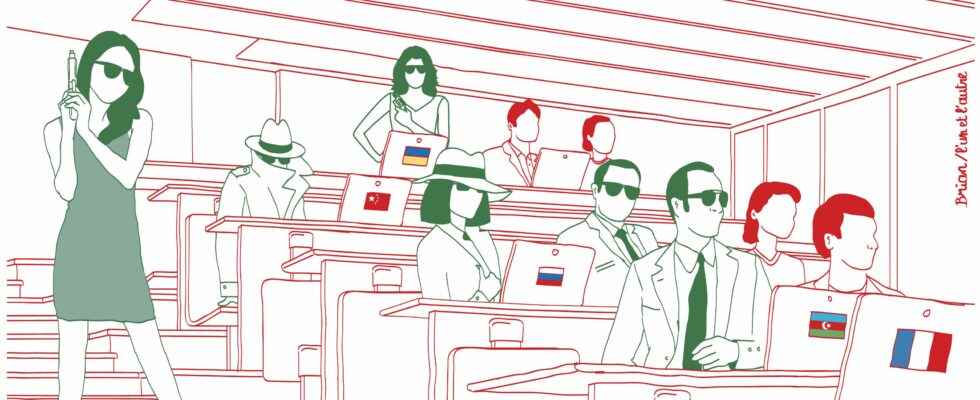

Seen from the outside of its pretty red brick premises, in this “new Latin Quarter” of the 13th arrondissement of Paris, near the François-Mitterrand Library, nothing distinguishes Langues O’ from another university, except perhaps to be the sociology of its students – Inalco is without a doubt the most mixed Grande Ecole in inner Paris. Inside, it’s a kind of university UN: you come across speakers of Chinese, Russian, Persian, Turkish, Arabic, Hebrew… All the most sensitive diplomatic issues of the era in one place. Enough to arouse the interest of foreign influencers, confirms Alain Chouet: “Someone who takes pains to learn a language, it is because he must have some sympathy for this country. For an intelligence service, it is a vein that it may be tempting to exploit.”

The precedents are known. In 1973 then 1979, the engineer Dimitri Volokhoff and Pierre-Charles Pathé, heir to the cinema industry, were convicted of spying for the benefit of the USSR. Two fervent Russophiles, who went through Langues O’. In the Mitrokhine archives, named after this KGB archivist who went to the United Kingdom in 1992 with his documents, we also discover… that a great professor from Inalco was a paid agent of the USSR. Franco-Chinese Jean Pasqualini spent seven years in a concentration camp in China, before being released and teaching Chinese at Langues O’. In 1974 he published Prisoner of Mao, his autobiography, then was recruited the following year by the KGB, under the code name “Chan”, according to Mitrokhine. In his lectures, he is said to have added to his account “elements fabricated by the KGB”.

Even today, “Inalco is obviously one of the priority objectives of the Russian services, it is a certainty”, assures Sergueï Jirnov, ex-KGB agent who has taken refuge in France since 2001. Jean-François Huchet, the president of the ‘Inalco, wants to be “vigilant” and confirms “an alert with a student association linked to Russia”, which the establishment has “cut short”. The teacher-researcher is sometimes solicited by embassies attentive to the work of the school, such as that of Azerbaijan, irritated by the last Transcaucasus festival of O’ Languages, too favorable to Armenia in his eyes. Inalco recently refused to take on two Azeri teachers offered by Azerbaijan, which did not accept that the establishment exercise a right of scrutiny.

Inalco under Chinese surveillance?

In his hunt for interference and propaganda operations, the president of Langues O’ benefits from feedback from certain professors. Uyghur and Tibetan teachers often see Chinese students with uncertain motivation arriving in their classes. “They say they’re interested, but often don’t make an effort to learn,” says Dilnur Reyhan, a Uyghur lecturer, who remembers in particular a student who insisted on integrating the WhatsApp loop of the course… before never to come. During the screening of a film on the disappearance of Uyghur activists, in March 2022 at Inalco, a young woman had to be escorted out of the room. “Nobody knew her. She monopolized the floor by reciting the Chinese regime’s propaganda, then started shouting,” says Dilnur Reyhan.

Françoise Robin, Tibetan teacher, notes that “every year, at least one Chinese student” joins her course, and this “since the start of the 2008 school year”, a few months after the disruption of the passage of the Olympic flame in Paris by pro activists -Tibet. “Recently, I had one who said nothing in class. On the other hand, he asked a lot of questions to the other students, especially my Tibetan student”, relates the university. He was also warned that he was still holding a strange tablet in front of him. “Was it to record? We have no proof. But we know that Tibetan studies are of interest to the embassy,” says Françoise Robin. When the Dalai Lama came to Inalco in September 2016, the Chinese embassy tried to have the conference canceled, requesting two meetings with the presidency, sending a letter calling into question the “maintenance the good relationship between Inalco and China”.

Jean-François Huchet, himself a specialist in China, still claims to have recently had to reframe a student association tempted by an operation “a bit limited” with China. From the start of the 2023 academic year, the president of Inalco wants to offer his international relations students “a course on foreign interference”: “It will not prevent embassies from canvassing, but at least the students will be made aware of these challenges”. An informed polyglot is worth two.