To respond to the threat of troops massed by the Kremlin on the Ukrainian border, Estonia had a plan: deliver to Kiev its forty-two 122 mm D-30s, a Soviet gun with a range of 15 km. But now, these artillery pieces were originally the property of East Germany. And Berlin, within the framework of European rules on arms exports, preferred to block the operation, as it has the right to do, revealed the wall street journal. It is out of the question to derogate, even indirectly, from its choice not to deliver lethal weapons to Ukraine – which does not exclude economic aid.

There is nothing anecdotal about this veto. If the Europeans all agree that a Russian attack against Ukraine would have a “high cost”, they are far from sharing the same analysis concerning the unusual deployment of more than 100,000 Russian soldiers, on the border with the Ukraine, eight years after the annexation of Crimea by Moscow and the secession of part of the Donbass, controlled by pro-Russian militias.

There are currently two opposing camps within the European Union. On the one hand, the Baltic countries and Poland, on the line of the United States, want to respond to the Russian threat with deterrence, with a list of precise sanctions and the sending of arms to Ukraine – the Estonia has already been able to deliver anti-tank missiles, Latvia and Lithuania anti-aircraft systems.

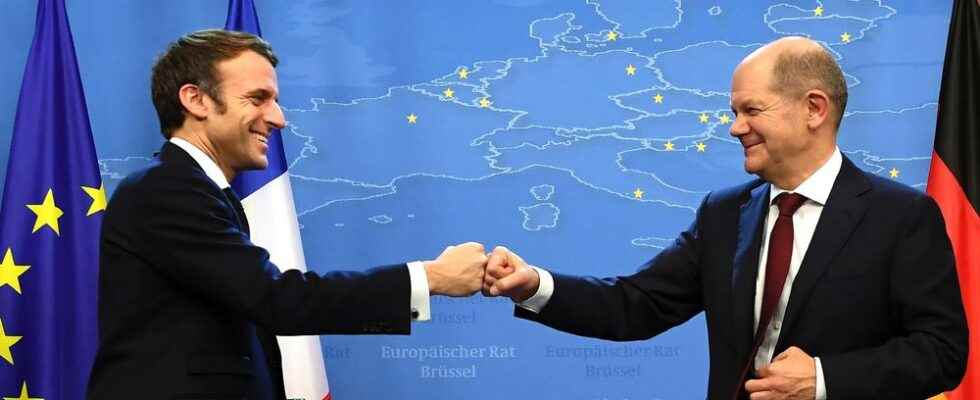

On the other hand, we find Member States calling for caution, starting with Germany and France. During a joint press conference with Chancellor Olaf Scholz in the German capital on Tuesday evening, Emmanuel Macron insisted on underlining the “very great unity” between their two countries on the Ukrainian crisis. And both pleaded to continue to “dialogue” with Vladimir Putin – a telephone exchange is planned for Friday between the French and Russian presidents.

Ukraine angry with Berlin

This positioning is reminiscent of that of former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, who used to say: “better to negotiate 100 hours for nothing than to shoot a minute”. The prudence of Berlin, on which Paris aligns itself, however, is going more and more badly. Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba thus accused Berlin of “undermining” Western unity and “encouraging Vladimir Putin to a new attack against Ukraine”. The output referred as much to the veto on the export of Estonian D-30s as to the remarks made on January 21 by the head of the German Navy. While in India, Kay-Achim Schönbach said the idea that Russia could invade Ukraine was “nonsense” – he had to resign the next day.

Emmanuel Macron and Olaf Scholz, December 17, 2021.

afp.com/JOHN THYS

Not sure that the soldier would have dared such an outing if his government had opted for more firmness. “As the continent’s leading power, Germany should guide Europe’s response to the current crisis by detailing sanctions against Russia in the event of an attack,” said Stefan Meister of the German Council for Foreign Relations (DGAP) think tank. Olaf Scholz’s lack of leadership irritates Washington as much as it weakens the Western approach, which plays into the hands of the Kremlin.”

The cause is known: the Social Democratic Party (SPD) is divided on the approach to take with Vladimir Putin, in the same way as German society, still marked by Ostpolitik, the rapprochement with the East made in the years 1970 by Chancellor Willy Brandt. Added to this is Germany’s strong dependence on Russian gas (51% of imports) and the fear that the Kremlin will turn off the tap. “We have to consider the consequences that [des sanctions auraient] for us,” Olaf Scholz said a few days ago. Among them: the renunciation of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which should allow him to import even more Russian gas without going through Ukraine…

For Berlin, we must therefore beware of provocations. “The Germans believe that going too far on arms deliveries or going into the details of sanctions could have a counterproductive effect and fuel Russian paranoia,” notes Marie Dumoulin, director of the Wider Europe program at the European Council on International Relations. . But this position has a price: growing mistrust on the part of its Eastern European partners.

Clement Daniez