I remember that in September 1972 Mark Spitz became, with his seven gold medals, the greatest swimmer in the history of the Games, and that he was Jewish, and that, when I was six years old, this was not going to not together. At six years old, I thought that a Jewish man was a man like my father, my uncle, my grandfathers who died before I was born, but whom I imagined on the same model; a man with flabby flesh who feared being constipated or prone to migraines. The practice of their body, as it was familiar to me, was limited to the experience of illness, the discourse to that of complaint and to how to heal this body which was functioning incorrectly. A Jewish body was frail, ailing, skin too light, without muscles, knew no other sports than a slow digestive walk in the forest on Sunday afternoon or the exploration of a museum or a museum with small steps. a sweater store. This lack of envelope was compensated for by their brains, they read books and told jokes. […]

I was a child who had perfectly integrated the classic anti-Semitic codes, a Jew was a being with a devirilized anatomy deserving to be exterminated. And Mark Spitz arrives, his golden and victorious body at the end of the summer of 1972. It was therefore possible to be Jewish and not to be like my parents, splendid Platonists celebrating their soul and contemptuous of their body, but to invest entirely in this body, to take it, in a Nietzschean way, as master? […]

When, on August 27, 1972, he stood for the first time on block number four, reserved for the person who obtained the best time in the heats, and he had to start the 200 meter butterfly, he was obsessed with a shadow that constantly sucks him in. When he thinks he can get rid of it, she taunts him, “you won’t make it”, reminding him as proof of his failure four years previously at the Mexico Olympics. He was nineteen years old, held the world record in this discipline, and finished eighth and last, beaten by his compatriot Carl Robie. The latter had raised his finger at him, exclaiming: “From now on, I am the American champion!” This last place will never disappear. When he recalled it, fifty‐three years later, interviewed at the edge of this same swimming pool in Munich, with the tall gait and curved shoulders of a seventy‐six year old man, he affirmed: “What happened spent in Mexico, it’s like it happened six hours ago.”

Mark Spitz

© / The Express

Mark Spitz is not Othello

On August 27, 1972, he knew that this shadow could prevent him from winning again. Our dark and invisible thoughts are the most destructive, because they are precisely hidden, we are not wary of them, we believe we can deal with them, beat them without anyone noticing. We are most often like Othello, the winner who always puts on a show, shows his strength, masks his fear which ends up breaking him. Mark Spitz is not Othello in deluding himself about his solidity, he observes his torments head-on and looks for a way to get around them so as not to be carried away by them. He only has a few seconds, before the start, on this point number four, to shift the pressure and the fear to the right place, not in this rotten Mexican past, but where it is possible for him to win. He shifts, transporting himself to a recent workout where he achieved a world record, remembering the warm-up he did that day, repeating the same arm and leg movements. He is no longer in Munich, but in this comfortable, familiar place, where he is at ease, and he dives and advances and breaks a new world record and wins his first individual gold medal. […]

In seven days, he participates in fourteen races, which means that as soon as one race is finished he moves on to another. Between two events, he has an hour and a half to receive his medal, drink, pee for doping control, eat, rest, warm up. He cannot think about what is happening to him, he has no time to be happy with his victory, to enjoy it. He climbs barefoot, his sneakers in his hand which he did not have time to put on, on the podium for his second individual gold medal, the 200 meter freestyle, and he raises them in a sign of victory . He is subsequently accused of clandestine advertising for a brand, a possibility of exclusion, the rumor reaches him, the Jews and the money. […]

“This lampshade was perhaps made with one of my aunts”

Finally, the queen event takes place, the one that makes you the fastest swimmer in the world, the only one where he is not the favorite, the only one where he does not dive from point number four, but from three. It took place on September 3, 1972, a date which refers to this terror which remains in the memories, September 1972, Munich, Black September, eleven dead, it will be in two days. Mark Spitz can still appear innocent, saying: “I have no problem with Germany, what happened is in the past, I was not born.” He doesn’t start slowly, hoping to save himself for the final sprint as he usually does, he sets off very quickly and wins his seventh gold medal, he is the best Olympian of all time.

And this triumphant man did his barmitzvah, fasted for Yom Kippur, felt the shame, say it or not, the fear that overtakes you. When he arrived in Munich, he couldn’t help but exclaim, pointing to a lamp next to him: “This lampshade was perhaps made with one of my aunts.” On September 5 in the morning, a police officer came to pick him up to warn him, you cannot stay, you will be secretly evacuated to London, then to your home in the United States, you are a target for the terrorists. His golden body does not immunize him from being Jewish.

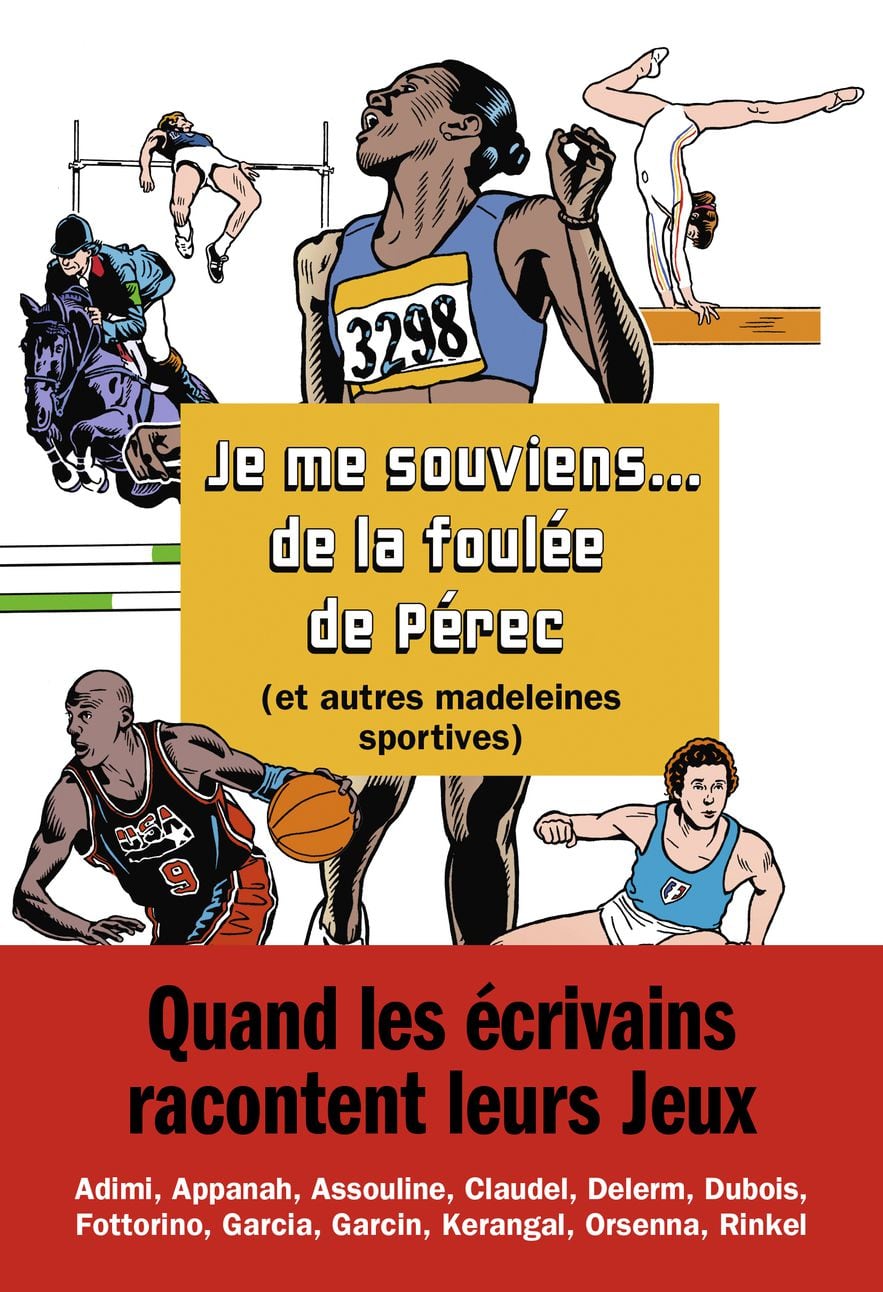

Taken from I remember… Pérec’s stride (and other sporting madeleines), directed by Benoît Heimermann. Threshold, 226 p., €19.90.

When 27 writers remember their favorite Olympics

© / Edition of the Threshold

.