Nairobi will kick off the busiest four months of the year for international climate negotiations this Monday, September 4, with the first “African Climate Summit”, culminating in a battle over the end of fossil fuels at COP28 in Dubai in December. L’Express takes stock of the issues on the eve of the start of the summit.

The Kenyan President on the move

For three days, some twenty leaders and officials from Africa and elsewhere, including UN chief António Guterres, will be welcomed in the Kenyan capital by the very active President William Ruto, who hopes that this summit will allow the continent to find a common language on development and climate in order to “propose African solutions” at the next annual UN climate conference.

In a world lagging far behind in its emission reduction targets, which are causing increasingly severe global warming for the people, the negotiations in anticipation of COP28, chaired this year by the oil and gas powerhouse of the United Arab Emirates , are marked by strong opposition on the energy future of humanity.

Along with other African leaders, William Ruto has worked to highlight Africa’s potential as a green industrial powerhouse and to call on the international community to unlock the money for the continent. “They have clearly shown that Africa is not a victim, but a key player in solving the global climate crisis through green growth”, analysis for AFP Mavis Owusu-Gyamfi, executive vice-president of the African Center for Economic Transformation (ACET).

The stakes are high: the continent is at the forefront of global warming. “All African states are responsible for only 6% of total CO2 emissions. However, on the continent, the consequences of climate change are particularly dramatic”, recalls in a column published this Friday by Young Africa German Minister for Economic Cooperation and Development, Svenja Schulze.

An ambitious program

A success in Nairobi would give impetus to several key international meetings before COP28, first in September the G20 summit in India and the United Nations General Assembly, then in October the annual meeting of the World Bank and the Monetary Fund. International (IMF) in Marrakech.

To limit global warming to +1.5°C compared to the pre-industrial era envisaged by the Paris agreement, investment must reach 2,000 billion dollars per year in these countries in the space of a decade. , calculated the IMF.

A draft “Nairobi Declaration” seen by AFP, but still under negotiation, underlines Africa’s “unique potential to be an essential part of the solution”. The document cites the region’s vast renewable energy potential, its young workforce and its natural assets, including 40% of the world’s reserves of cobalt, manganese and platinum, essential for batteries and hydrogen. It also includes a commitment to triple the potential of renewable energy on the continent, from 20% of electricity in 2019 to 60% by 2030.

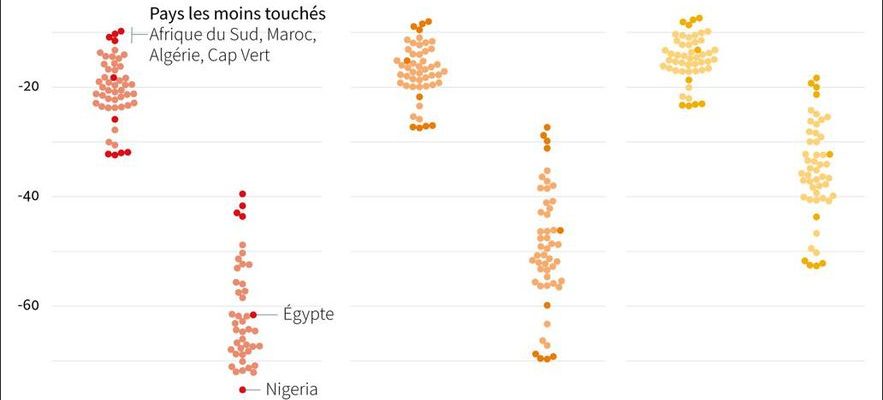

The development of Africa weighed down by global warming.

© / VALENTIN RAKOVSKY, ANIBAL MAIZ CACERES / AFP

Financial barriers

Countries like Kenya are ahead, with about 94% of its electricity coming from renewables. But African leaders continue to point out the considerable financial obstacles for their continent, among the most vulnerable to climate change and where some 500 million people do not have access to electricity. Africa, which is home to 60% of the world’s best solar energy potential, however, only has an installed capacity similar to Belgium, the Kenyan president and the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA) recently pointed out. ). In question, in particular: only 3% of the world’s investments in the energy transition arrive in Africa, they declared.

The debt burden in the region has skyrocketed with the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and climate impacts, says the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, warning against the risk of a “lost decade” for its development. Moreover, the rich countries have not yet kept their promise to increase their aid in the fight against climate change to 100 billion dollars a year: a promise that has not been fulfilled since 2020, which has permanently eroded the confidence of poor countries in the ability of incumbent greenhouse gas emitters to assume their responsibility.

For Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, Africa had to distance itself from the global struggles between China, the United States and Europe. “We will thus be at the table, and certainly not on the menu, as we have been so far”, he summarizes with AFP. “We skipped the landline step, the same way this continent […] can skip the dirty energy stage and become a green leader”.