On April 25, 1974, a coup d’état put an end to 48 years of dictatorship and opened the way to democracy and European construction. (Rebroadcast)

Special 50 years of the carnation revolution with the Portuguese-speaking service from RFI

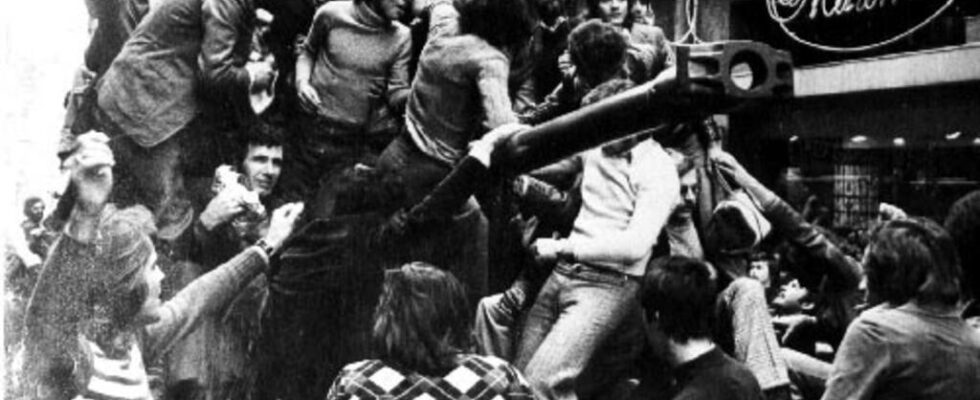

April 25, 74, has remained in history and memories as the day of the Carnation Revolution. A revolution whose roots and consequences extend beyond the country’s borders, from Africa to Europe. In 1974, the dictator Salazar had already been dead for 4 years. His succession did not allow the country to return to the rule of law, and the military, worn out by colonial wars, overthrew the totalitarian regime and opened the country to democracy.

With Yves Léonard, historian specializing in Portugal. Author of “Under the carnations the revolution: April 25, 1974 in Portugal», 2023.

Juliette Gheerbrant: To On the occasion of the anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, RFI in Portuguese is publishing a rich series of podcasts, “Revoluçao dos Cravos” for which you went in search, from Lisbon to Paris, of resisters to the dictatorship; can you share some of these encounters?

Testimonies of participants in the revolution by Carina Branco, by Domingos Abrantes, by Marie Teresa Horta

Carina Branco: First there is Sunday Abrantes80 years old, and his wife Conceição Matos, who got married when he was in prison. He stayed there for 11 years, she for a year and eight months. They were tortured by the political police. Like all opponents of the dictatorial regime, they were accused of threatening national security for belonging to the banned Portuguese Communist Party. But he also committed “another crime”: he was part of one of the most spectacular collective escapes of that time. It was in 1961 and with seven comrades, they forced the main gate of the Caxias prison in a luxury car, not just any car as he says: “It’s a story worthy of a movie. It went down in history. It was a politically charged escape from a private prison of the PIDE, the political police, in an armoured vehicle belonging to the dictator! It is said that Salazar never wanted to set foot in the car again because it had been defiled by communists! It took 19 months to prepare the escape, made possible thanks to the complicity of the mechanic in charge of these vehicles, who had managed to gain the trust of the guards. A risky bet for the fugitives: The car rushed towards the gate and the big unknown was: what will happen?… It was the decisive moment. If the car doesn’t get through, we’re all dead. It was the decisive moment of the whole story, of our lives. The car got through, it broke down part of the gate and we saw the wood flying through the air. It was completely dented at the front. The escape lasted 60 seconds. It took 19 months to reach 60 seconds. But those 60 seconds seem to have stopped time.

Under the dictatorship, as you mentioned, torture was widespread. What did the witnesses tell you?

Domingos Abrantes remained standing for days and nights, unable to sit or sleep, he suffered electric shocks, the “hole” – a cell where neither light nor sound entered and where he felt buried alive). “The role of the police, he explainswas to destroy the organized struggle because fascism could only be overthrown by struggle. There was no other way. The people were poor, exploited, but they were capable of risking everything to improve their lives and the lives of others. His wife, Conceiçao Matos, was also subjected to sleep deprivation, forbidden to go to the toilet, humiliated and beaten by the guards, as she recounts: “One of them grabbed me, they took my clothes off and she started kicking me in the shins, hitting me in the face, hitting me… It was terrible and I fell to the ground. They picked me up, and continued. And at one point, after many hours, the woman said: Let’s leave, because this shit won’t talk and if I stay any longer, I’ll kill him. ! » In 1973, Conceiçao Matos and Domingos Abrantes were able to go into exile in Paris to continue their struggle. They returned to Portugal just after the revolution on board the so-called Freedom Plane, which brought many political exiles from Paris to Lisbon.

Despite the violence of the repression, the resistance was therefore very active?

Many of the people I met knew that sooner or later they would go to prison, but they each acted at their own level, like the priest Francisco Fanhais, who supported the LUAR, League of Union and Revolutionary Action, and who also resisted through music. He recorded, alongside the musician Zeca Afonso, the song that would become the symbol of the revolution: Grândola Vila Morena. Some attacked the military apparatus intended for the colonial wars. The resistance was also active in the editorial offices and the publishing world. The journalist Helena Neves explained to me how it was constantly necessary to play with censorship in the newspapers to succeed in telling the story of the country between the lines. The political police banned books considered subversive. One of the most famous is called New Portuguese Lettersalso known as the book of the three Marias, it tells the story of the condition of women and was written in 1972 by three of them, including Maria Teresa Hortanow 86 years old, whom I met: “It is a political book, essentially political, written in a fascist country by three women. At that time, in Portugal, it is not surprising that this book had the effect of a bomb. It caused a scandal. For me, and for others, it was a glimmer of light because we lived in this fascist country with an intrinsic sadness, and also an immense feeling of internal and external revolt. In fact, we only understood that this book could be “dangerous” for us when it was banned.” The dictatorship considered the book “pornographic and offensive to public morality” and the authors were threatened with a sentence of six months to two years in prison, because it discussed without taboo sex, desire, but also violence, rape, incest, clandestine abortion, domestic, social and political oppression of women. But also colonial wars, poverty, emigration. Published in 74 in French, by Éditions du Seuil, it is a powerful testimony of what Portuguese society was like under the dictatorship.

Testimony Guinea-Bissau and the role of the anti-colonial struggle in the carnation revolution of Ernesto Dabo.