Published on

updated on

Reading 1 min.

Air pollution caused by ultrafine particles (UFPs) emitted by transportation and industrial activity causes 1,100 premature deaths per year in Canada’s two largest cities, according to a study published this week.

These “extremely small” particles, which are not regulated, “penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream“, Scott Weichenthal, lead author and professor at McGill University, told AFP.

They can be “harmful” and contribute to the development of heart and lung diseases, as well as certain forms of cancer, says the expert behind this first study of its kind conducted in Canada.

Along with other researchers from Canadian universities, he measured air pollution levels between 2001 and 2016 in neighbourhoods in Montreal and Toronto with a total population of 1.5 million adults.

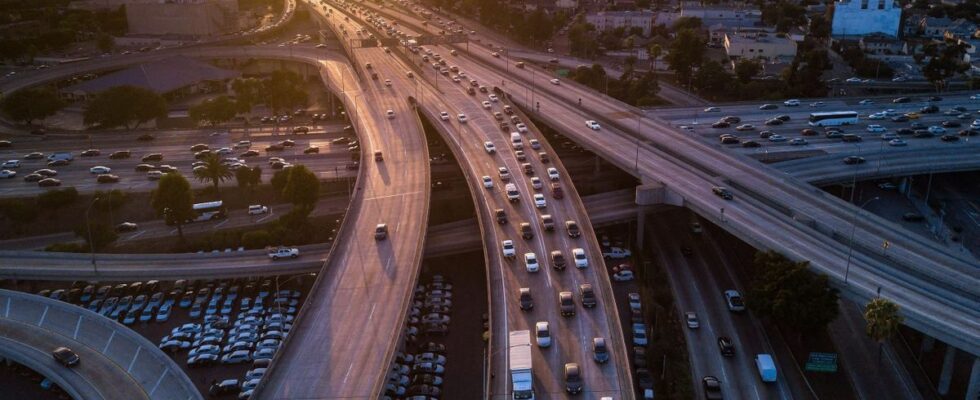

Areas located near major highways, airports and marshalling yards in particular had higher PUF concentrations, which is consistent with observations from studies carried out in Europe.

The researchers then used “statistical methods” to establish a correlation between the rate of exposure and the risk of death.

The results published in theAmerican Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine report a 7% increase in the risk of non-accidental death in areas where residents have long-term exposure to ultrafine particles.

These conclusions highlight “the urgency of implementing regulatory measures to target these particles“, says Scott Weichenthal, and to combat air pollution in urban areas.

Solid suspended particles with a diameter of less than 100 nanometers (1,000 times finer than a hair), ultrafine particles are supposed to be harmful to health due to their ability to penetrate the body, but are not currently subject to regulation.

PUFs are in fact less well known than their larger sisters, PM10 and PM2.5 (fine particles), whose harmful effects on the human body are scientifically established.

Scott Weichenthal says the study is likely the first to look at variations in the size of ultrafine particles and their different health impacts.

Previous studies that did not take this into account may therefore have underestimated the extent of the health risks, he adds.