This is an important step that Neuralink is preparing to take. After years of animal testing, Elon Musk’s brain implant company is looking for a partner to conduct clinical trials on humans. At the end of March, Reuters revealed that it had approached one of the largest neurosurgery centers in the United States, the Barrow Neurological Institute, for this purpose. Last year, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejected an initial request from Neuralink on this subject, citing major risks, while its rival Synchron announced its first human brain implant placement in the United States. The race is launched with immense prospects. Neuralink, Synchron and Paradromics raised $363, $120, and $56 million, respectively.

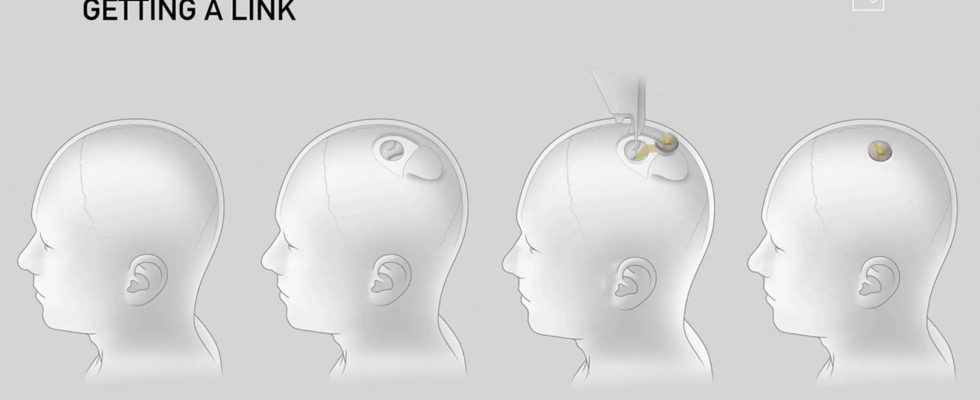

The medical risk associated with these devices is relatively controlled. A recent study concluded that there were no deaths or disabling complications in 14 adults who had received a brain implant since 2004. The point-shaped devices that penetrated the cranial box will increasingly give way to less invasive devices. Synchron has thus developed a device similar to a stent inserted through the jugular to reach a vein in the motor cortex.

The deciphering of the electrical signals received has, meanwhile, progressed at a brisk pace. In January, a team from Stanford University published a study where the thoughts of a person unable to speak intelligibly due to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis were translated at the rate of 62 words per minute, which is 3.4 times faster than the previous record and beginning to approach natural conversational speed (about 160 words per minute). The error rate on a vocabulary of 50 words was 9.1%, or 2.7 times less than the state of the prior art. As in any technological race, the material barriers will eventually fall under the battering of researchers as long as funding flows.

The “augmented” human market

It is inevitable that these devices go beyond the curative framework to satisfy a desire to increase intellectual performance. This is the vision proclaimed by Elon Musk from the start but also that of his competitors. Even though they prefer to hide behind repairing individuals, they obviously see a much larger market in their improvement. It is also the vision of millions of people who, today, try to measure their cerebral activity using headbands carrying out electroencephalograms to better meditate, sleep better or regulate their emotions.

The two questions that then arise are those of ethics and sovereignty. Many doctors are working on the increased risks of addiction linked to these devices, in view of the one we have contracted vis-à-vis our smartphones. Some brain implant patients developed a kind of decisional paralysis, unable to choose what to eat without first consulting the device that showed what was going on in their brain. Sometimes a patient relies so heavily on their device that they feel like they can’t function without it. Several cases of patients who fell into depression after losing support for their devices at the end of a medical trial have been documented. The sample of people concerned is much too small to give statistical strength, but these first qualitative feedbacks deserve to be taken into account.

The other subject is that of sovereignty. The data captured by these devices is the most valuable in the world, much more than knowing if you are likely to buy blue sneakers or even who you are ready to vote for. Can we imagine that these devices are not entirely manufactured on national soil under conditions of security and absolute integrity without any possible leakage? All the aforementioned start-ups are American, with Synchron founded in Australia now having its headquarters in New York. China has found its champion. Last December, NeuroXess, created in 2021 in Shanghai, raised tens of millions of dollars to continue the development of its semi-invasive device composed of silk protein electrodes that can avoid blood vessels and thus minimize damage. As for Europe, it is once again absent from this global race.