In Brazil, there has always been someone to remark: “Pelé is the best football player in history. But he is more concerned with his advertising contracts than with the rights of black people”. Edson Arantes do Nascimento, known as Pelé, who died this Thursday, December 29 at the age of 82, would he be guilty of indifference towards his brothers and sisters of color? If his prodigious sporting career and his status as “King” has never been disputed, the man with three World Cups has in any case often been accused of having been complacent with the military dictatorship and of not having engaged in the fight against racism in a country where racial discrimination is, despite appearances and received ideas, deep. In this huge country, more than half of the 200 million inhabitants are black or mixed-race and suffer from a subtle form of discrimination which bears a name: “cordial racism”.

When Pelé was still Edson

Even though slavery ended in 1888 – Brazil was the last western country to abolish it – racial segregation persisted. Especially in football. In the 1930s, the clubs were monopolized by the whites and the elite. At the time, players were forced to smear their faces with rice powder, like a kind of talcum powder, to “whiten” their skin. Arthur Friedenreich, one of the first great Brazilian players, smoothes his frizzy hair with brilliantine. In his Praise of dodging, the writer Olivier Guez tells precisely how the Brazilians invented the dribble to avoid the charges of the Whites who were never sanctioned by the referee. At the time, the Brazilian press even went so far as to blame the terrible defeat against Uruguay in the 1950 World Cup final on the team’s black players, in particular Barbosa, the unfortunate Seleção goalkeeper who released the ball in his goal…

Edson Arantes do Nascimento is also regularly confronted with racism in Bauru, a city in the interior of the state of Sao Paulo where he grew up, raised in a poor family by Dona Celeste and Dondinho, his father, a pro player in career shattered by a knee injury before joining the Santos club where he would become a true legend. Pelé experiences the bitter experience of discrimination when his first white girlfriend is abused by her own father… for dating a black man. Then he meets Rosemeri Cholbi, another white woman, with whom he will marry and have three children. But there’s no question of showing up in public when the lovebirds start flirting even as Pelé’s notoriety increases.

“They were not to be seen together. And when they went to the cinema, someone from his family accompanied them. Edson could only enter the room when she was installed”, says Angélica Basthi, journalist and author of an unauthorized* biography on the man with 1,200 goals: Pelé, Estrela Negra Em Campos Verdes (Pelé, black star in the green fields, 2011, untranslated). He also receives the worst nicknames that refer to his color: “Gasolina”, gasoline in Portuguese like the black color of oil, “Alemão” (“German”), to mock the opposition between Pelé’s physique and that European players”, the “Criolou” (the mestizo), or “Saci Pererê”, a one-legged black Brazilian folk character…

Silent during the military dictatorship

Pelé experienced his hour of sporting glory in the midst of a military dictatorship (1964-1985). In Brazil, these years of lead are marked by extremely brutal repression. Activists are arrested and tortured – especially blacks – freedoms are suspended. General Emilio Garrastazu Médici, in search of international credibility, then uses Pelé, already crowned with two world championship titles, and the prodigious team of 1970 (Rivelino, Tostao, Jairzinho…) as a showcase for his country before the news competition organized in Mexico. “He has been criticized a lot for not having said anything and, once he has won his third World Cup, he will go directly to Brasília to be received by the head of the junta, without, however, showing any support for the military regime”, recalls Eduardo Rihan Cypel, Franco-Brazilian, former deputy and lecturer at Sciences Po. journalist, will stick to his skin: “Brazilians don’t know how to vote”. The implication: elections are superfluous.

Spirito Santo, author a blog on racial issues very followed in Brazil and professor of Afro-Brazilian music at the State University of Rio de Janeiro, sees in the attitude of Pelé a cultural reflex. “I remember that my father and my mother instilled in me the fact of avoiding confronting racism, says this black intellectual who took part in the armed struggle against the dictatorship. The protocols of domination were very powerful and the repression often very violent. Many blacks were therefore forced to adapt to the system”, analyzes this activist. “Pelé was marked by the myth of racial democracy,” adds biographer Angélica Basthi. A concept – debatable – dear to the sociologist and writer Gilberto Freyre (1900-1987) according to which Brazil would be a kind of paradise without discrimination between whites and non-whites. But from the 1960s, the black movement called Frente Negra Brasileira (Brazilian Black Front) became more active following the model of the civil rights movement in the United States against Segregation.

As for Pelé, it will take a long time for him to sketch a mea culpa in a documentary on Netflix where he talks about the Brazilian dictatorship: “I don’t think I could have acted differently, I’m not a superman or a miracle worker. I was a normal person who God allowed to play football. But I am absolutely certain that I did more for Brazil with my football than many politicians paid to do so.”

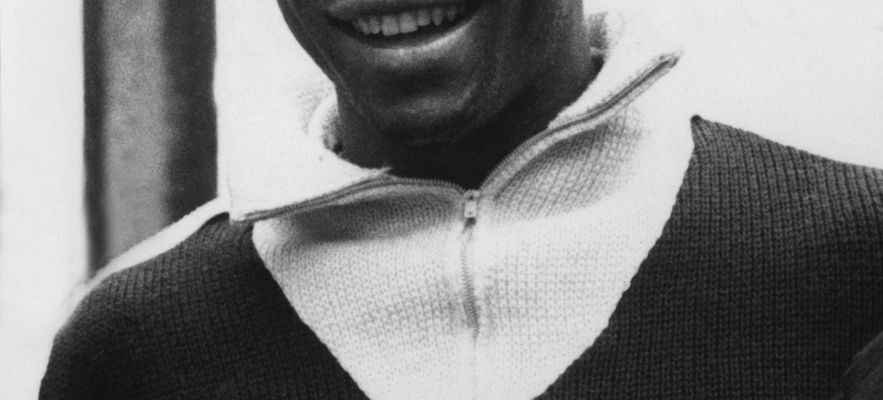

Pelé, June 1, 1962, in Vina del Mar in Chile, before a World Cup match against England.

© / AFP

Nelson Mandela and Mohamed Ali are his mentors

From there to say that Pelé has no political opinions, there is only one step. When in 1995, Social Democratic President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, alias “FHC”, appointed him Minister des Sports, until 1998, we believe that he has definitely embarked on a new trajectory. A time, a few years earlier, some had even imagined him as a candidate for the supreme election! In reality, his foray into politics is only a parenthesis. But Pelé will have been courted all his life by presidents wishing to benefit from the image of a winning Brazil. Juscelino Kubitschek (1955-1960), João Goulart (1961-1964), FHC (1995-2002), Lula (2003-2010) and even Bolsonaro (2018-2022), known for his racist projections, who posts, in the midst of a pandemic of Covid-19, a jersey signed by the “King”.

The image of an “apolitical” was reinforced by a very hushed, almost papal communication, throughout his life where the prodigy of the ball prefers to stick to more consensual themes, such as peace in the world. with the “end of the war in Ukraine” or global warming. He piles up honorary functions like trophies: he was designated a citizen of the world in 1977 by the UN before becoming an ambassador for Unicef and Unesco… And yet all his idols are illustrious militants of black causes: the boxer Mohammed Ali – “my hero”, he will say when he died in 2016 – and Nelson Mandela who died in 2013. “He was my hero, my friend, my companion in the fight for the cause of the people and for the peace in the world”, he wrote on his Twitter account.

Black people want access to the country’s universities

The multiple television spots for different brands, ranging from luxury watches to sodas to credit cards, have alienated the first player in history to become a millionaire from the Afro-Brazilian community, in search of progress and mobilized by fighting. All are calling for better access to the country’s universities, equal pay (a black earns on average half as much as a white), as well as the end of the “black genocide underway in the favelas”, adds Spirito Santo while in Brazil a black man is killed by homicide every 23 minutes.

“As an activist, I would have liked him to say more. As a biographer, I would say that he was consistent all his life”, sums up Angélica Basthi. Pelé was simply “devoured by football, his art”, concludes Eduardo Rihan Cypel for whom Pelé “subtly nailed the beak to racists by showing that a black man could be the symbol of success”. Discreet and emotional, Pelé has often claimed to have made only one promise in his career: to dry the tears of his father who cried when Brazil lost their World Cup on home soil in 1950. The objective was achieved.