Continue to serve the State. At all costs. Continue to calculate, evaluate, construct scenarios, run mathematical models full of equations. Continue, yes, but for what? And for whom? Since the dissolution of the National Assembly and the political fog of the second round of the legislative elections, the Budget department at Bercy has not been idle. A silent and docile shadow army. The linchpin of a work essential to the proper functioning of the nation: the construction of the budget for the coming year. Without a budget, no State. Without a budget, no public services, schools, hospitals. No police, judges, military. Without a budget, chaos.

Whatever its political colour or mix – grand Republican coalition or tight-knit team of sharp experts – the preparation of the finance law will be THE priority project of the next executive. A thankless, technical but politically explosive task. A balancing act between often fanciful campaign promises, European constraints, the reality of the country’s budgetary situation and the fragility of the balances in the National Assembly. Except that with the political big bang, the well-oiled machine has been completely disrupted.

And yet everything had started well. As every year, by the end of spring, the 200 or so agents of the Budget Directorate had already started writing the future finance law. The “budget conferences”, a high-sounding name to describe the working meetings between the various ministries and the Minister responsible for Public Accounts, Thomas Cazenave, had even begun, turning as usual into discussions between carpet merchants to agree on the credit ceiling for the following year. Amélie Oudéa-Castéra, the Minister of Sports, and Stanislas Guerini, the Minister of the Civil Service, had already been put through the wringer. And then, bang, everything stopped on Monday, June 10. “Why continue when everything has gone to hell”, confides today a minister who is very busy preparing for her arrival at the National Assembly.

Unsigned “ceiling letters”

“I’m not in flip-flops on the beach,” Bruno Le Maire recently retorted during a meeting with journalists. Before finally letting go of the helm, the captain of Bercy since 2017 is working to polish his record. 1,000 billion in additional debt under the Le Maire era? An absurd figure that would mean nothing: debt only makes sense in relation to the wealth created each year. With this reading grid, the drift would only be… 353 billion euros. A large sum, certainly, but a trifle compared to the two historic crises – Covid and the inflationary shock linked to the war in Ukraine – that France has experienced in recent years, maintains the minister. Above all, Bruno Le Maire wants to leave the accounts clean, if not square, silence the rumours about possible hidden holes, and show that he can bring the public deficit down to 5.1% of GDP at the end of the year as planned, compared to 5.5% last year.

To do this, in addition to the 10 billion in credits frozen in the spring, the increase in the franchise on medicines, the increase in the tax on electricity consumption, he promises another 10 billion in savings for 2024, including 5 on state spending alone. But what about 2025? The technical work continues, they say in the minister’s entourage. Understand, all the work around the macroeconomic framework, the growth and inflation forecasts, which will make it possible to establish projections of tax revenues for 2025. On condition, of course, that the tax rates remain unchanged. The famous “ceiling letters”, which set in stone the credits of each ministry, have indeed been drafted but the minister will not sign them. It is up to the new team to put these promises and political choices into practice.

Three crisis scenarios

Except that time is running out. A hellish ticking clock guided by the iron law of the Constitution and our European commitments. On September 20, Paris must send its new multi-year public finance program to the Brussels Commission. Then, the draft finance bill for 2025 must be submitted to Parliament by Tuesday, October 2 at the latest and adopted before December 31. Once the text is submitted, a period of seventy days begins during which the two assemblies – first the Palais Bourbon, then the Senate – can amend the texts, delete certain articles, vote on or reject certain provisions. A torrent of amendments to study. Then, it is back to the National Assembly – the famous parliamentary shuttle – with the passage to the joint committee where the final arbitrations are negotiated. Finally, from mid-November, a vote on the budget at second reading, first on the expenditure side and then on the revenue side. So much for the theory. Except that during these seventy days, anything is possible and the destiny of France can change at any moment.

Will the future government want to force through with the joker of Article 49-3 as Elisabeth Borne did last year? The problem is that it would then be exposed to a motion of censure which, given the narrow balances in the Assembly, could bring it down. The second scenario is the stagnation of parliamentary work and the exceeding of the seventy-day deadline without a vote: “The government could then pull out the card of ordinances provided for in Article 47 of the Constitution to adopt the budget. But such an action would lead to an unprecedented political and institutional crisis and it has, in fact, never been used,” dissects Jean-Pierre Camby, professor of law at the University of Versailles – Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines and former administrator at the National Assembly.

Third scenario, that of a negative vote in the Assembly at the end of the seventy days. The government would then not have time to rewrite a new copy, given the incompressible deadlines, and it could ask Parliament to pass a law authorizing it to raise taxes to allow “the continuity of national life”. The expenses, themselves, would simply be renewed, an exact copy of those of 2024. Twice, in the history of the Fifth Republic, such sleight of hand has been observed: in 1962, when the Pompidou government was the subject of a motion of censure in October, and in 1979, when Raymond Barre’s draft Budget was rejected by the Constitutional Council.

A seven-year cure?

A very tense autumn is therefore on the horizon, under the scrutiny of our European neighbours. “Germany knows how fragile coalitions are, and Berlin has no interest in triggering a confrontation,” reassures Maxime Darmet, chief economist for France at Allianz Trade. Germany, yes, but what about the other frugal countries, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland and a whole host of small countries quite annoyed by the undue privilege granted to Paris for years? The new Commission, for its part, may also want to mark its territory and show that the new budgetary rules that Europe has adopted, and that France has largely pushed for, are not just on paper. Of course, Emmanuel Macron and Ursula von der Leyen have long been on the same page, but the President of the European Commission owes her second term more to the support of the German right, which is very sensitive about the use of public funds, and the EPP than to the help of the French President. “The European Council is a meal for big cats and Macron is clearly weakened,” comments a Commission bigwig.

Placed in an excessive deficit procedure, Paris must theoretically propose a credible path to redress public finances accompanied by a plan to reduce spending. How much? And for how many years? France could thus ask the European Commission for a grace period to spread its “slimming cure” over seven years, and not four as specified in the new rules of the game. Seven years, precisely, the ideal period to find 110 billion euros in savings, reduce the deficit, stabilize the public debt ratio and above all not to break growth too much, according to a study by the Strategic Analysis Council to be published soon. “The problem is that during the lightning legislative campaign, we only talked about spending but never about savings. Within the New Popular Front, everyone knows that it will be necessary to disappoint the voters, but no one dares to admit it,” observes one of the authors of the study, the economist Thomas Philippon, professor at New York University. Who will dare to come out of denial first?

Private debt has also exploded

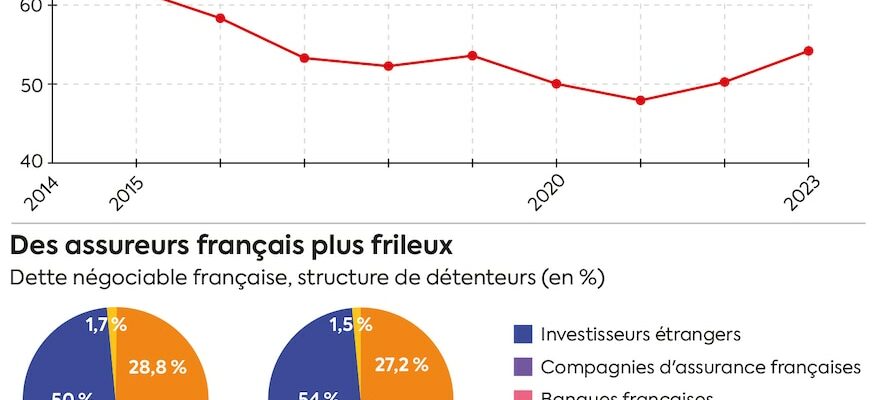

A very unstable period is therefore beginning. However, international investors, insurance companies, pension funds, many of them European but also American, Japanese, Singaporean, Chinese, are lying in wait. A little over 54% of the French public debt is in their hands. The famous “spread” – the gap in interest rates – between German and French debt, a true gauge of the state of anxiety of the financial markets, certainly climbed after the dissolution, but it did not disappear after the results of the second round. For the time being, they are mainly waiting for the dust to settle. Of course, they need French debt securities in their portfolio, particularly for regulatory reasons with regard to the Europeans. But not necessarily as much.

3811 cover financing

© / The Express

“This political crisis has created a magnifying glass effect and the concern is palpable,” observes Gilles Moec, chief economist of the Axa group. “They are discovering that France is suffering from a very French illness, that of the preference for debt,” adds economist Eric Chaney. Because it is not only public debt that has exploded in recent years, that of the private sector too, and in particular that of companies. Thus, according to the latest assessments by the Bank for International Settlements, total debt – public and private – reached 320% of GDP in France at the end of last year, compared to an average of 236% in the euro zone, 183% in Germany, 235% in Italy and 256% in the United States. Only Japan is doing worse.

A hexagonal disease that could cause growth, already not very strong, to stall in the event of panic among investors and a rise in interest rates. “If foreigners are less greedy, French investors, particularly banks, could take over, they have room to spare and are not very invested in French securities”, believes a banker from the Parisian market. After all, that’s what happened in Italy and Japan. Unless everyone in their own corner decides that Paris is definitely not a party place…

.