You had to be at the University of Cambridge between 2014 and 2020. During this interval, it was possible to consult the entire archives of Vassili Mitrokhine. This former KGB colonel was the chief archivist of the Russian intelligence service between 1972 and 1984. Methodically, this disillusioned with Sovietism copied these documents on a daily basis, in the hope, one day, of defecting to the West .

In 1992, the fall of the USSR gave him the chance of his life. He went to the United States embassy in Latvia, which turned him away, then turned to the United Kingdom. He then brings his treasure, thousands of pages of secret service operations, with the names of agents recruited from 1917 to 1984. His production has been authenticated in all Western intelligence agencies, to which the British submit their discoveries , from 1994. In the United Kingdom, Germany or the United States, what is beginning to be called the “Mitrokhine archives” will give rise to confessions from spies in the pay of the USSR. In France, on the contrary, it was quickly decided… not to investigate these findings. Too sensitive.

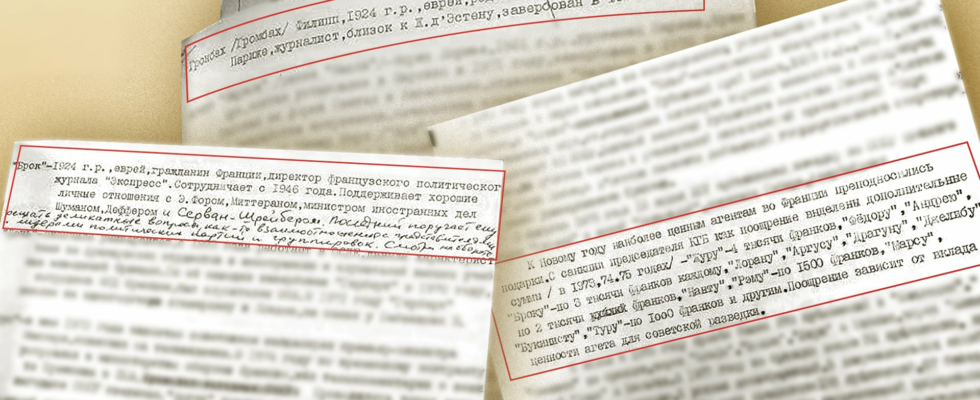

These archives first give rise to a book, The KGB against the West, co-written by Christopher Andrew, historian specializing in British intelligence, translated in France by Fayard. But Vassili Mitrokhine’s wish was for these documents to be fully accessible to the general public. In 2014, ten years after the death of the Russian defector, the University of Cambridge opened the data for consultation. Their content fueled several investigations by L’Express, first, in February 2024, on the betrayal of its former director, Philippe Grumbach, then on Russian political espionage up to the Elysée, last December.

Cyril Gelibter, now a doctor in political science at Paris-Sorbonne, heard about these Mitrokhine archives while he was preparing his thesis on the Iraqi weapons of mass destruction affair. He went to Cambridge first time, then a second time. In 2020, the university administration informed him that certain sections of the Mitrokhine archives could no longer be consulted. Application of the GDPR regulations on personal data, officially. Gelibter had time to photograph most of the documents. Today he provides a particularly expert analysis of this exceptional data, part of which is still freely available.

Our investigations into Russian spies at the Elysée

EPISODE 1 – Russian spies at the heart of the Elysée, our revelations: how the DGSI protects presidents

EPISODE 2 – “André”, the KGB spy at the newspaper “Le Monde”: the last secrets of an elusive agent

EPISODE 3 – A KGB spy alongside General de Gaulle? Investigation into the Pierre Maillard affair

EPISODE 4 – A KGB agent in the Assembly: our revelations about Jacques Bouchacourt, alias “Nym”

EPISODE 5 – Pierre Sudreau, the minister very close to the KGB: these unpublished documents which say a lot

EPISODE 6 – AFP journalist and KGB mole without knowing it: the incredible Jean-Marie Pelou affair

EPISODE 7 – A “relay spy” between Mitterrandie and the USSR? The thousand lives of “Colonel” Harris Puisais

EPISODE 8 – Alexandre Orlov, the diplomat who became Vladimir Putin’s agent of influence in France

EPISODE 9 – Alexandre Benalla and the mysterious Russian contract: investigation into his links with the oligarchs

EPISODE 10 – Our revelations about these Russian spies who reached the heart of the Elysée: “The number one threat is…”

L’Express: How did you gain access to these KGB archives known as Mitrokhine?

Cyril Gelibter: I was preparing my thesis on intelligence services and weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. I wanted to know what the KGB had to say about it. Obviously, by contacting the press service of the SVR or the FSB, I would have gotten nothing. I’m going to Cambridge in March 2018, for two or three days. I am amazed at the amount of information available. There are entire pages with lists of KGB agents, often with their real names, their functions, their place of birth, sometimes the date of their recruitment. In December 2018, I examined the archives in more detail for a week. I must have consulted 70-80% of the entire Mitrokhine fund.

How are these archives presented? By country, by type of agent?

It depends. There is a classification by geographical areas, and there is also a classification by themes, for example scientific and technical intelligence, which is the subject of separate treatment.

Is their content consistent with what is written in the reference book on the subject, The KGB against the Westwritten in 1999 by historian Christopher Andrew?

Yes, but Christopher Andrew didn’t publish everything in his book. Perhaps due to lack of time to sort everything, but also, in my opinion, with the wish to avoid certain scandals. For example, I discovered a large mole in Indonesia. According to a note, the Indonesian ambassador to the USSR, Adam Malik, was recruited by KGB counterintelligence. He then served as Indonesia’s foreign minister from 1966 to 1977 and then vice president of Indonesia from 1978 to 1983. The memo does not specify whether the KGB continued to “treat” him or not. We can clearly see the controversies that the publication of his name would have aroused. There was also perhaps the desire to serve a certain narrative on Andrew’s part: that of the penetration of the West by the KGB and that of the Machiavellianism of the Soviets.

Are these documents still freely accessible?

Not all! I had this surprise when contacting the University of Cambridge again in 2020: certain files had been closed. Officially, this involved complying with GDPR regulations on the protection of personal data. Despite Mitrokhine’s desire to see his archives published in full. I redid the test recently, dozens of pages are no longer available, including for France.

Are we sure that these archives are authentic?

Yes, in any case, we have no reason to doubt. Vassili Mitrokhine was subjected to a demanding debriefing, all of the intelligence services contacted considered his information to be authentic. Furthermore, they gave rise to confessions and discoveries in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. In France, there is the case of Philippe Grumbach, revealed in L’Express at the beginning of last year. In the event of a fake, there would need to be a motive. What would have been the interest of the KGB in denouncing some of its secret agents? There isn’t one. I don’t believe in disinformation from the English either. What’s the point?

Can we not imagine that certain KGB officers exaggerated the complicity of certain public officials in the countries where they spied?

Yes, it’s entirely possible, and probably has been the case at times. KGB residents had to follow the center’s guidelines, so they might exaggerate their achievements in order to conform to expectations.

Can we imagine that certain agents mentioned in the archives existed only in the minds of these bureaucrats?

Regarding the people mentioned as agents, I doubt they are fabrications. The recruitment of secret agents was very bureaucratic, requiring the agreement of the center in Moscow, after a study. So it’s much more serious. Cases of possible exaggeration concern more the personalities whom the KGB considers to be “contacts”, without their fully collaborating.

What should we think of these “confidential contacts” cited as linked to “active measures”, in fact KGB disinformation or propaganda operations? Could they have been unaware that they were considered that way?

Yes, the distinction is difficult to make between the naive, the falsely naive, and the spy. I would point out, however, that it is possible in certain cases. The journalist Pierre-Charles Pathé was arrested in 1979 then sentenced to five years in prison in 1980 for articles supporting the theses of the USSR.

He was convicted because money payments were revealed. What analysis should be done when these transactions do not exist?

There are indications that point to a clandestine relationship, outside the “classic” diplomatic framework. First of all, a meeting with an intelligence agent is never trivial, it is not a diplomatic relationship like any other. It is therefore necessary to know if the person understands who they are dealing with. Are these meetings hidden? Are documents exchanged? Is there any consideration, money, gifts or an invitation?

How can we explain that there were neither investigations nor convictions in France following the publication of the Mitrokhine archives?

Around 1994, the DST decided not to investigate. I don’t know exactly why but it’s a very political decision, which was taken at a high level.

And should these archives be considered exhaustive? Is there anything related to the KGB in the Mitrokhin documents?

No, some files are not mentioned. Mitrokhine probably didn’t have access to everything, and he didn’t write everything down either, he didn’t have the time, he made choices, according to his interests.

These Mitrokhine archives draw attention to Russian espionage in France, but are there other countries spying on us with the same success?

Thanks to Mitrokhine, we have more information on Russian espionage in France. But I have no illusions about American espionage. They spy on us a lot! The rare revelations on the subject, for example in a recent book by Vincent Nouzille, are edifying. We discover thanks to notes, notably from the CIA, that Ambassador Jean de la Grandville delivered state secrets to the Americans because he was against General de Gaulle’s choice to disengage from NATO.

We can also refer to the memoirs of former CIA officers: it is stated there that during the Cold War, they had 60 to 80 handling officers in France, not so far from the USSR, which had around a hundred. Paris also serves as a base for recruiting foreign citizens who are in our country. In his memoirs, Mission man: life lessons from a CIA operative, BD Foley, a former CIA agent stationed in Paris, gives some examples.

More generally, the Chinese, the Moroccans, the Algerians, the British, the Germans… everyone is spying on us. Sometimes in a more modest way, everyone also carries out “active measures”, mixing propaganda and disinformation, against us. A current example: a “report” prepared by the Center for Defense Reforms, a Ukrainian think tank headed by former secretary of the Ukrainian Security Council Oleksandr Danylyuk, who is also linked to the Royal United Services Institute, a think tank British. This report implicates former French soldiers and intelligence officers who are allegedly in the pay of the Russians. Except that several of the people cited – not all – are pro-Ukraine! Maybe not enough for their taste.

.