“And you, what do you do for a living? – Writer. – How I envy you, but apart from that, what is your job?” The fact is that “it” is not one, nor is it a profession since, with a few exceptions, we do not make a living from it. Then what ? A state of mind, a view of the mind, a sensation of the world, the list is not exhaustive. In the middle of the literary prize season, it is not inappropriate to look at the occupation which in principle allows them not to have problems from the end of the month to the beginning of the month. If you find one among those who exercise the office, certainly noble but in danger, of kiosquier, beware of any amused condescension and the slightest bit disdainful: he is perhaps the next winner of the Goncourt. There is at least one for whom this has succeeded.

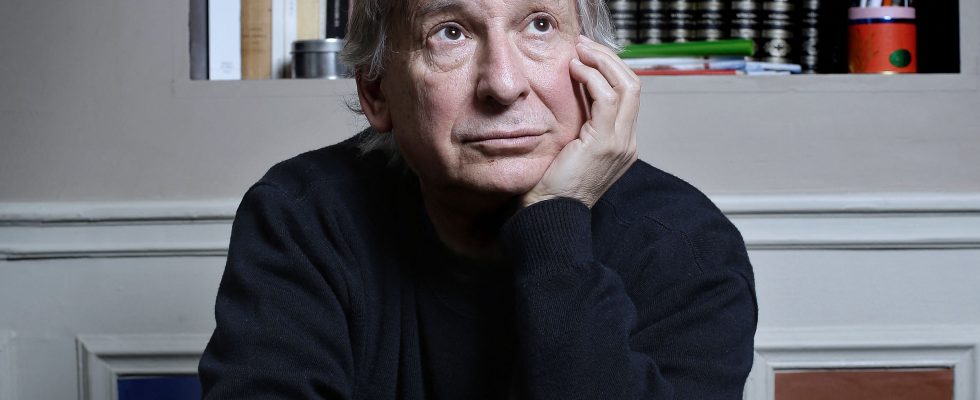

His name is Jean Rouaud and he tells us about it these days in detail in Autumn comedy (Grasset). What a beautiful Bergman title! Everything is said about the spirit of prices. Theater at the best of times, with its share of vaudeville, drama, passions, intrigues, maneuvers and tragedy. In the worst case, Grand Guignol. It was in 1990. Rouaud had written a novel entitled The Fields of Honor, three destinies within a family against the backdrop of the First World War; the austere Jérôme Lindon, head of the equally austere editions of Minuit, published it. Appearing in their catalog gives the first-time novelist the illusion of being dubbed by Samuel Beckett himself. From his editorial epic, the timid foray of a Lunar Pierrot from Campbon (Loire-Atlantique) into the Germanopratin shark lake (Paris 6th), he has drawn a mischievous story full of self-deprecation, which would be even more delicious if it was not tinged with disenchantment. It all started with an investigation by a journalist (yours truly, if you allow me…) into the professions of writers. The latter having lunch as usual with publishers, he gleaned from Jérôme Lindon that one of his back-to-school authors was, as incredible as it may seem, a newsagent.

As soon as the article appeared, the rumor spread in literary circles that the great back-to-school novel was authored by a simple newsstand established at 101, rue de Flandre (Paris 19th century); the media laid siege to the place before, during and after the event, to the great joy of the inhabitants of the Stalingrad district, delighted that it was mentioned other than for stories of syringes and drug dealers. From then on, this plaster will not be detached from its name for a long time; but the more we talked about him, the less we talked about his book. Enough to create “a misunderstanding, a confusion, a shift of interest”. Anxious not to betray the world of the humble from which he came without ever having had the absurd idea of racializing it, he played his role. The most popular newsstand in Paris. With François-René, Viscount of Chateaubriand as tutelary figure, which does not encourage modesty but maintains humility. This kiosk which made his glory, basically, he spent seven years there before building a work; as to Fields of honor, they met with immense success, both public and critical. More than thirty years later, we still read it, study it and talk about it as if it had just been published, which testifies to its powerful inscription in the memory of readers.

The elegance with which Jean Rouaud reports his stay at the front, the press officer who calls him a “puddle” after a broadcast, Pierre Michon who assures him that he deserves the Goncourt for his Tiny lives more than him for his Fields of honor not without apologizing shortly after by showering his novel with praise, Bernard Rapp ensuring its cathodic glory, “le Favori” published by Gallimard to whom the Académie Goncourt had promised the reward convinced of being the victim of a plot of academicians keen to cover their tracks by exploiting it, the said conspiracy subsequently proving to be perfectly accurate and the trap proven, all of this is told with the lightness that befits the life of literary society. Rouaud has no equal when it comes to engaging in it with the detachment of a spectator from his own existence. Is every quest for a great literary prize nothing more than a vanity fair that degrades into a race for the shallot?