“Before leaving, I still have a mountain of paperwork to fill out!” While some of her final year classmates anxiously scrutinize the progress of their wishes in Parcoursup, Maëlle Bukiet refines her application file for immigration to Canada. Next September, the 18-year-old girl will join McGill University in Montreal. “To integrate this institution which ranks among the 30 best schools in the world was my dream since entering high school! , she exclaims. I had moreover put all the chances on my side by choosing the option international baccalaureate, which allowed me to be taken on file without having to take an English test.” According to the latest Campus France study, which has just been made public, 108,654 French students have, like her, chosen to continue their studies abroad in 2020. This represents an increase of 25% since 2015.

The phenomenon, if it is not new, has continued to grow in recent years. This is confirmed by Bruno Magliulo, former academic inspector and specialist in orientation questions: “Every time I speak in high schools or in student fairs, I do not escape questions from parents who are wondering about the best courses to follow abroad or the most popular destinations. This is a real growing concern.” Proof of this enthusiasm, the major international awards – such as that of the FinancialTimes or the QS World University Rankings – are also scrutinized by the most initiated families, mainly from wealthy backgrounds. “The French are obsessed with rankings!” Confirms Marc McHugo, founder of the consulting firm Study Experience, while warning about the limits of these criteria: “These tools can be useful, but it is important to know how to decipher them.” Some universities monopolize the first places thanks to their performance in research, which can be interesting for a young biology enthusiast, less for one who is destined for business studies.

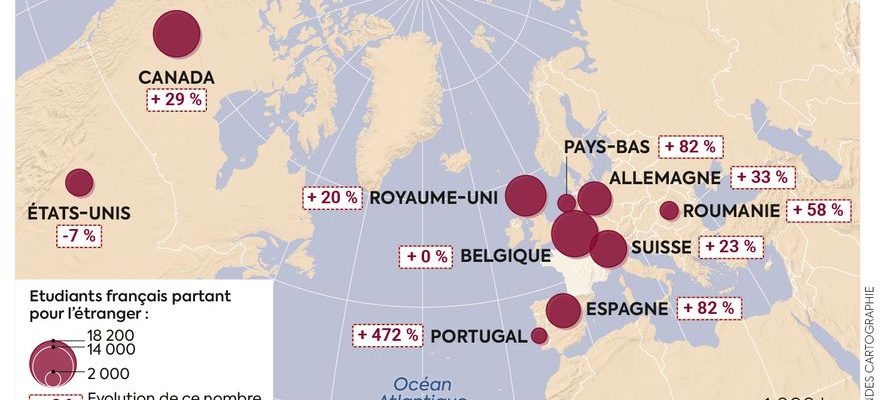

Canada, Belgium and the United Kingdom on the podium

According to Campus France, the most coveted countries remain French-speaking countries such as Canada (Quebec attracting the bulk of the workforce) which recorded a 29% increase between 2015 and 2020, then Belgium just behind, and Switzerland which is rising in fourth place. The United Kingdom, if it remains in third place, is expected to lose ground in the coming years due to the sharp increase in tuition fees since Brexit. Anouk Stricher, who went to the international school of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, joined the popular University of Leeds in 2019. At 21, she is completing a master’s degree in strategic marketing. Still in England. “In addition to the very high quality of the education system, I was seduced by the student atmosphere that reigns throughout the city and by the huge campus”, explains the one who created a podcast dedicated to international students. “Leaving after the baccalaureate deserves careful consideration because the potential difficulties of integration should not be underestimated. Studies show that 10 to 15% of young people return during their first year”, underlines Bruno Magliulo.

© / Cartography legends

Some of the motivations that push these students to embark on the adventure despite everything are now well known. Securing their backs in case the infernal Parcoursup machine leaves them empty-handed is one of them, especially for those who are targeting the very selective health sectors. Many of those who do not manage to get the grail of the first year in France no longer hesitate to pack up their bags to pursue studies in medicine, physiotherapy, dental care or nursing in Spain, Portugal, Romania, in Croatia or the Czech Republic. Other young people of course highlight the need to master foreign languages in their professional life. In the upscale French high schools circulate the names of the most popular European schools or faculties of the moment, whether it is the Bocconi in Milan, the Esade in Barcelona, the IE University in Madrid or the Rotterdam School of Management in the Netherlands. Down.

Another trend continues to grow: that of leaving to follow a Bachelor’s degree – in particular a Bachelor in Business Administration (BBA) or a Bachelor in International Relations (BIR) – in other countries… to better return to France three or four years later and try to enter the Grandes Ecoles through international parallel admissions. An alternative to traditional preparatory classes.

Going away for a while does not mean giving up on HEC, Essec, Polytechnique or Sciences Po, which are very fond of this type of profile. For Lionel Sitz, director of the Grande Ecole program at EM Lyon, this post-baccalaureate experience abroad has something to appeal to the examiners responsible for selecting the candidates. “It’s a maturity accelerator! French students who join us after winning an international title show greater adaptability and better resistance to stress. They have also acquired other ways of thinking, work or think,” he says. Before also praising a certain “linguistic plasticity”: “As in The Spanish inn and all of Cédric Klapisch’s films, they have this ability to switch from one language to another, which is a huge plus.” This also makes it possible to acquire these famous “soft skills” – behavioral skills – which today make the difference on a CV.

If many candidates for departure already have a well-defined plan, others rely on this period of exile to refine their career. Certain streams, such as the Liberal Arts Colleges, which are particularly advanced in the Netherlands and the United States, are attracting more and more students because of their multidisciplinary dimension. “This contrasts with the French system which forces young people to specialize very early. Once on track, it is very difficult to deviate from one’s training. Which is less the case in general internationally where there are more flexibility,” notes Marc McHugo. Anya Jasinski, who is entering her third year of Bachelor Liberal Art and Sciences at Leiden University in The Hague, wanted to take the time to think about what she really wanted to do. “After having dabbled in a bit of everything, I opted for justice and international law as a major in the second year,” explains the 21-year-old girl who still intends to continue her law studies in France thereafter.

Anouk Stricher has decided to stay in England to start her professional career there. Which is far from being the case for everyone. “Most of the students we support plan to come back later because it reassures them to pursue a French diploma” explains Adam Girsault, co-founder of Your Dream School. This company helps students to choose the foreign university that will correspond to their wishes, their academic profiles, their plans for the future… but also to their budget. Because, obviously, this type of course has a significant cost and is often reserved for the most privileged families. English universities, in particular, are increasingly inaccessible. “It takes between 15,000 and 30,000 euros per year,” explains Adam Girsault. According to this specialist, other destinations are much more affordable. Like that of Quebec since French students pay Canadian and not international tuition fees. Ditto for Ireland where the university applies European rates, or Sweden where some courses are free. Still need to know. However, to the barrier of money, are added the failures of our orientation system. Once again, all high school students do not leave with the same chances at the entrance to higher education.