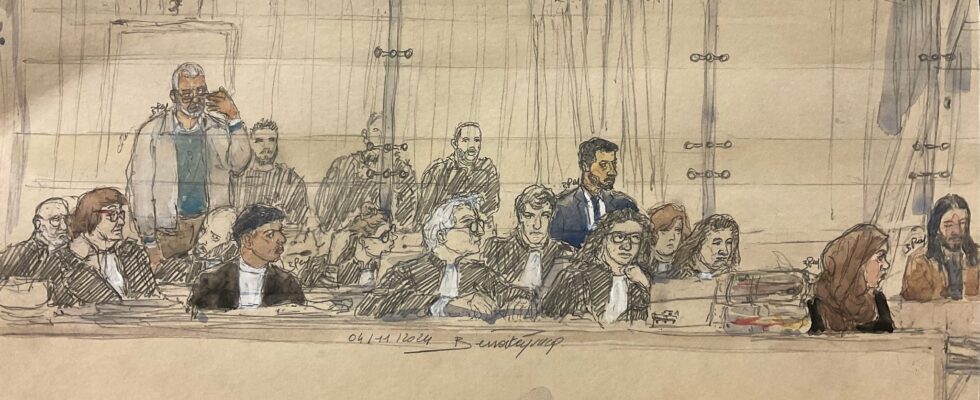

Conversations fell silent, cell phones were placed on silent mode. In the heart of the Paris courthouse, the excitement of around thirty high school students, delighted to discover the grandeur of the place and to take a selfie in front of the buildings, transformed into a studious concentration at the entrance to the The huge special assize court where terrorism cases are judged in particular. On this afternoon of Tuesday, November 19, these final year students are well aware of what is at stake: they are attending, with their history-geography teacher and the French Association of Victims of Terrorism (AFVT), the third week hearings in the context of the trial for the assassination of Samuel Paty. When the President of the Court, Franck Zientara, enters, the students stand up simultaneously, notebooks in hand, ready to take notes. Most have never set foot in a criminal court, let alone attended a terrorism trial. “We know it’s going to be strange to see the accused a few meters from us. It’s a bit chilling,” confides Delia, 17, a few seconds before the start of the hearing.

When Samuel Paty was beheaded outside his college in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, on October 16, 2020, for showing his students caricatures of Mohammed, Delia was 13 years old. She herself was in fourth grade, in a college in the Paris region located a few dozen kilometers from that of Bois d’Aulne, where the history and geography teacher worked. “Teenagers of our age were involved, not far from us… It shocked us all a lot,” recalls the teenager, who remembers the minute of silence organized in tribute to the teacher, the class debates on the caricatures and freedom of expression, or the “few reports” seen at the time on television. “But the details of the case, the sequence of events, the penalties incurred by the alleged accomplices, the way a trial works… I had no idea before working on it this year,” breathes the young girl, who is destined for a career “in the law”.

As the hearing begins, she scans the court, observes the defense lawyers, those of the civil parties, tries to recognize faces in the accused box. The latter are not unknown to him: before the trial, Delia and her comrades produced a trombinoscope of the eight people suspected of being involved in the murder of Samuel Paty, listened to the eight episodes of a France Inter podcast on the subject, read press articles, watched explanatory videos… “We have a lot of very shocking details in mind. But we also have the chance to attend this trial, to know the issues, and to observe justice live do his job”, believes her friend Lina.

“Have you ever been scared?”

Like 34 of their classmates in the “Law and major issues of the contemporary world” option, Delia and Lina have been working for several weeks on the “Paty affair”. In collaboration with the AFVT, their history-geography teacher Sophie Davieau set up the project “Paty trial: classes in audience”, the final objective of which is to collectively write an account of the entire trial, based on the presence of students at the assize court, press articles, podcasts, live tweets or meetings with different legal professionals. The day before, lawyer Antoine Casubulo Ferro, counsel for Samuel Paty’s colleagues – who became a civil party to the trial – came to meet the final year students directly in their class, in a high school in Courbevoie.

“My job will be to show that the teachers at the Bois d’Aulne college, where Samuel Paty taught, are also direct and indirect victims of the attack. How to continue teaching after that? How to return to class when your friend was beheaded? That some students denounced him to the terrorist? The moral damage is immense”, insisted the lawyer in front of a packed class. Her presence at the heart of the project is precious for Sophie Davieau: with pedagogy, Me Casubulo Ferro explains to high school students the important nuance between the accusations of “terrorist criminal association”, and “complicity in terrorist assassination”, the penalties incurred by the accused, the importance of the terms used during the expert assessments and pleadings.

A hesitant hand is raised. “Are you frustrated with the sentences the defendants risk?” asks a student. “No, since they risk the maximum sentence,” replies the lawyer straight away. Same assurance on the subject of “life imprisonment”, which the council diverts by indicating “to be for the individualization of sentences”, or on the vocation of lawyer, summarized by a quick: “It was a childhood dream “. “And have you ever been afraid?” asks another high school student after a short silence. White in the room. Me Casubulo Ferro wants to be honest. “Sometimes yes, even if it’s rare. After what happened to Samuel Paty, when I went to talk about the affair on a television set, I would sometimes look behind me when I came home”, he blurted.

“If it happened in my high school, I would react”

At the hearing the next day, the students listened with particular attention to the summaries of the psychiatric experts concerning the personalities of Naïm Boudaoud and Azim Epsirkhanov. These two friends of Abdoullakh Anzorov are accused of complicity in terrorist assassination for having helped him buy the knife which was used to decapitate Samuel Paty and for having left it at the scene of the crime. “It’s important to know their past, to follow the events in their life that may have led to this, and to understand how and why they can be judged responsible for this act in court, four years later,” says Maya. after almost four hours of hearing. This high school student remains particularly marked by the sequence of events. “It’s just painful to think that Samuel Paty was murdered like that, for that,” she sums up simply.

With her classmates, Maya confides that she has debated the subject of caricatures many times – a theme that would never have come to the heart of their teenage discussions “without the work done with Ms. Davieau”. “We all agree on the fact that we may not like certain designs, but that we have to live with it, because it’s freedom of expression,” she says, shrugging her shoulders. “If it happened in my high school, and I heard a student start to spread lies about a course or turn students against a teacher because of a caricature, I would react. I would tell him to be careful what he says, and especially to whom he says it,” assures the high school student.

Same assessment for Delia, who indicates having “changed her mind” on the subject of religious caricatures. “I admit that at first I found it a little humiliating and offensive. Now I understand that not at all. That it was freedom of expression, and that it should not be take it personally,” explains the Muslim student. Around her, the teenager opens the debate with friends or family: “My cousin is entering fourth grade and is going to study the subject of caricatures. I explained to him that if we showed him images of our religion, he should not not bad to take it, and he understood.”

A small victory for Sophie Davieau, delighted to train what she calls “watchers” or “vigilantes”. “Obviously, this trial has a very particular dimension as a teacher. By studying it, we also discuss questions of freedom of expression, secularism, caricature, blasphemy, which can be complicated in certain classes,” underlines the professor, also secularism referent within the establishment. In the coming weeks, seven other classes will attend half-day hearings at the Paris courthouse with the teacher and the AFVT. “I have not yet had feedback from my students, but I have no doubt that it will have an impact on them. And if I manage to convey these subjects with patience and nuance, it’s a winner “, concludes the teacher.

.