“The ultimate sporting challenge.” This is how in 2012 Robin Knox-Johnston summed up the solo round-the-world sailing trip, non-stop and without assistance, more than forty years after opening the way for future extreme sailors. In 1968, during the first edition of the Golden Globe, the British sailor became the first man to accomplish this feat, the only one then to complete the race, this ancestor of the Vendée Globe which would be born at the end of the 1980s, under the led by Philippe Jeantot, and keep the planet in suspense.

This November 10, 2024, 40 skippers, including twelve internationals, six women and two disabled sports competitors, will set off again from Les Sables-d’Olonne to try to conquer the Everest of the seas. On the occasion of this anniversary edition, the tenth in its history, the Musée de la Marine in Paris is presenting an exhibition that is both chronological and scientific, which follows the route of the most famous race, from the Bay of Biscay to the rise of the Atlantic. Between the two, twelve mythical stages, illuminated by navigation objects, models, works of art, interactive installations and video testimonies, take the visitor as close as possible to the human, technological or meteorological realities of the adventure.

At the cutting edge of engineering

Gone are the days of the pioneers who took to the starting line with rough boats. “In 1968, we didn’t know if a boat and a man could survive such a long journey together,” says Robin Knox-Johnston, who, that year, a few hours before the gun went off, was still modifying the rigging of his sailboat while completing life insurance forms for his family. Prehistory… Now, prepared by cutting-edge technical teams, monohulls are real war machines. “In thirty-five years, their performance has doubled as their weight has halved,” underline curators Lénaïg L’Aot-Lombart, from the Musée de la Marine, Olivier Le Carrer and Didier Ravon, navigators and journalists. offshore racing specialists. Gone are the over-equipped aluminum and fiberglass “safes”, make way for the carbon hulls, as light as they are robust, the keel angling at 40 degrees and the foils allowing the 8 tonnes of the boat to be lifted to let it fly over the waves.

Jean-Yves Terlain aboard “UAP 1992”, leaving the Vendée Globe, November 26, 1989.

/ © Didier Ravon / Alea

Hazardous areas

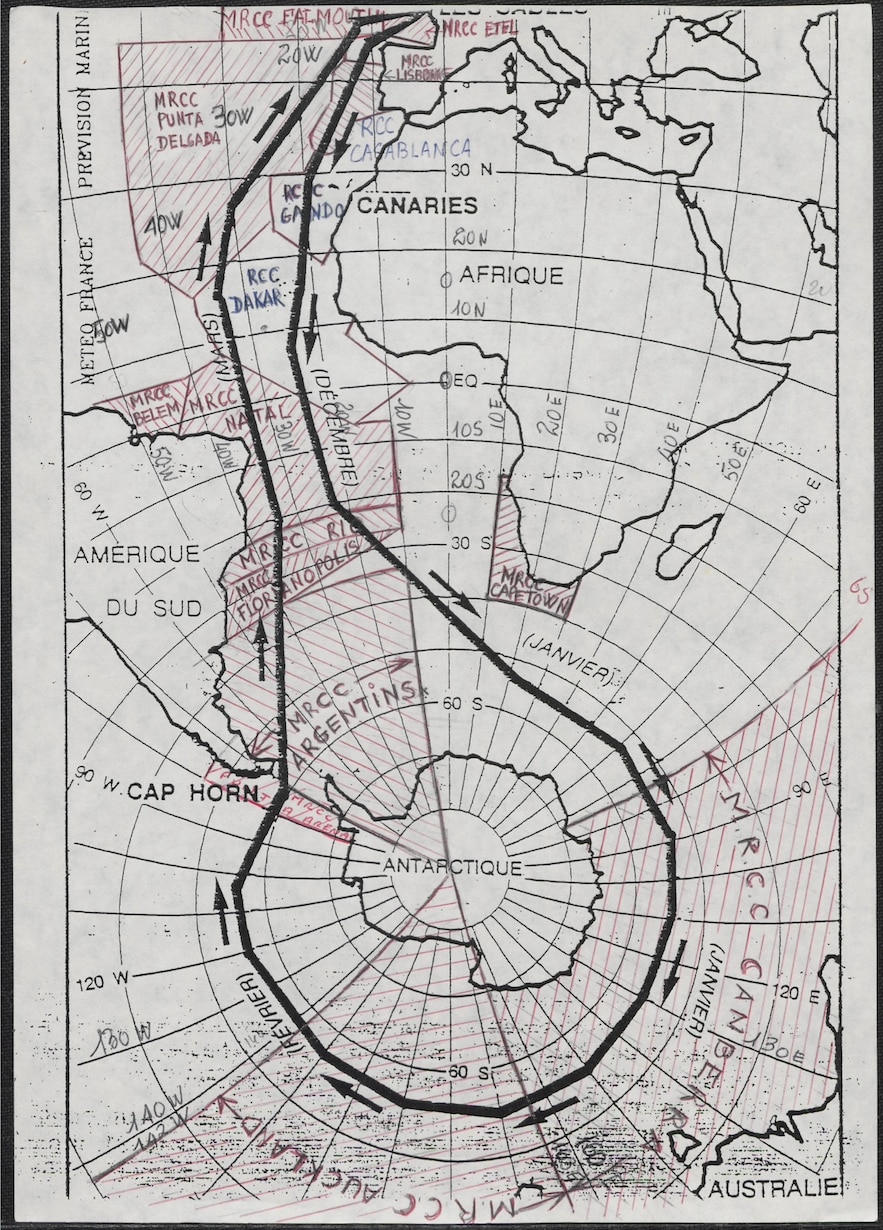

Three milestones must be crossed by navigators, three complex stages, each with its own pitfalls to avoid. That of Good Hope, firstly, at the southern tip of Africa, south of Cape Town, feared for its violent currents, marks the passage towards the South Seas. During the first Vendée Globe, faced with damage, Jean-Yves Terlain was forced to disembark there on February 11, 1990 and was greeted by a jubilant crowd: after twenty-seven years spent behind bars, Nelson Mandela had just be released. Cape Leeuwin, at the southwest tip of Australia, then constitutes for the skippers, who manage to overcome it, a gateway to the Pacific and its extreme conditions. Then, at the end of Tierra del Fuego finally comes the holy grail: the legendary Cape Horn, left to port, which marks deliverance and the route back up the Atlantic.

Map of the route of the first Vendée Globe Challenge, 1989.

/ © Morbihan departmental archives

In the meantime, the sailors will have faced two other obstacles as mythical as they are perilous. The roaring forties, where the risk of collision with the fragments of icebergs that global warming has multiplied, requires constant vigilance. Over the years, many competitors have broken their noses there, like Philippe Poupon, miraculously rescued by Loïck Peyron in 1989, or, more tragically, the Canadian Gerry Roufs who, before disappearing there on January 6, 1997, sent a final message: “The waves are no longer waves, they are as high as the Alps”.

Another nightmare for solo runners, the screaming fiftieths and their share of lurches: polar temperatures, raging seas, incessant din, high risk of breakage. Injuries, for their part, keep appearing throughout the crossing: in 1996, Bertrand de Broc sewed his own tongue raw in the middle of the Atlantic, with remote assistance from the race doctor. When it comes to repairs, the sailors have to fend for themselves: in 2001, Michel Desjoyaux managed to restart the broken down engine which powers the on-board batteries thanks to the power of his mainsail, and won the event in 93 days. Eight years later, he would become the only sailor to post two victories in the Vendée.

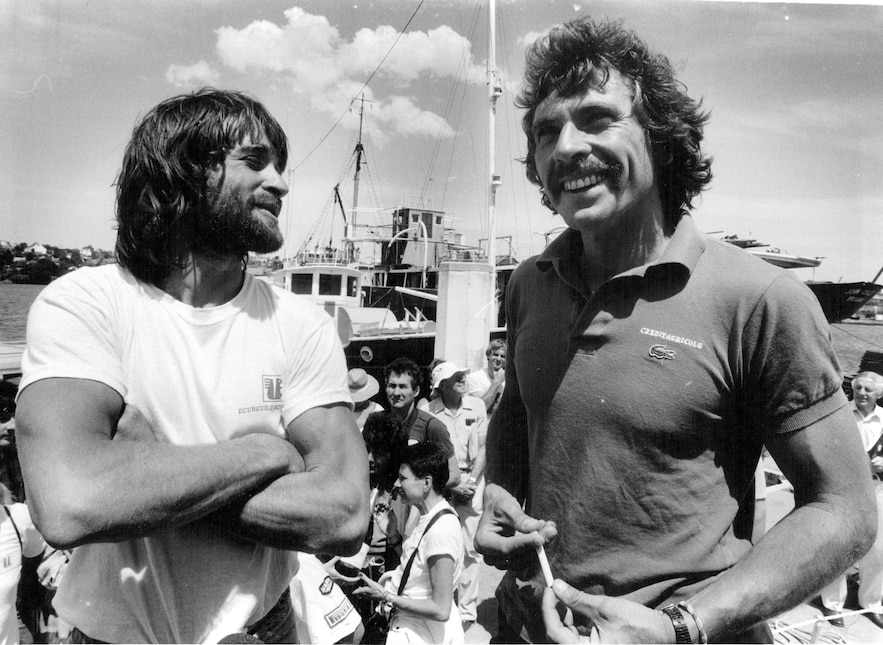

BOC Challenge, Titouan Lamazou and Philippe Jeantot, Sydney, December 15, 1986.

/ © Photo Brendan Read / Fairfax Media Archives / Getty images

Sailor and… artist

Two men have also left an indelible mark on the history of the race. Armel Le Cléach, nicknamed the “Jackal” for his pugnacity, is the current record holder with 74 days on the clock in 2017. And Titouan Lamazou the only artist to have participated. In the 1980s, the Fine Arts graduate, who loved travel and photography, interrupted his creative journey for a dazzling maritime break, which began alongside Eric Tabarly and was crowned in 1990 by his victory in the first Vendée. Globe, in front of Peyron, Poupon’s rescuer a few weeks earlier. Here, solidarity comes into play, both at sea and on land. “Day and night I felt a whole team who, on the ground, modeled their lives on mine,” declared Lamazou after crossing the finish line. Returning long ago to his first vocation, we find him today in a beautiful book, Under the stars (Gallimard), and at the contemporary art museum in Les Sables d’Olonne, where he exhibits his paintings probing the mysteries and fragility of the biosphere. An atypical inventory of the planet echoing the skippers who, not far away, will set sail on a new quest for the Everest of the seas.