Homo Sapiens, the species to which modern humans belong, has existed for at least 300,000 years. Maybe even more. For millennia, almost nothing has changed. As if Homo Sapiens were suspended in time. The flints found 300,000 years ago are almost identical to those dating from 200,000 or 80,000 years ago. And then, about 70,000 to 50,000 years ago, something clicked almost everywhere on Earth. Sapiens changes. It evolves. It was then an explosion of new technologies, ornaments, paintings, weapons, in a movement which progressed at an increasingly rapid pace, until reaching our modern societies. While Homo Sapiens had dedicated itself, for hundreds of thousands of years, to identically reproducing what the ancients did, it radically opted for change.

But what could have happened? This is the question that Ludovic Slimak, archaeologist and CNRS researcher at the laboratory of the Center for Anthrobiology and Genomics of Toulouse, tried to answer through a trilogy, the last volume of which, Naked sapiens: the first age of dreams (Odile Jacob) has just been published. “The upheaval came from what happened in the head of Man: there was an evolution of the imagination,” he postulates. To support his thesis, the “researcher-thinker” unfolds a fascinating fresco which invites us to philosophical reflection on ourselves.

L’Express: For years, it was the theory of a biological upheaval or a genetic mutation that was the favorite to explain the “awakening” of Sapiens. You explain that it has since been ruled out and that we must look at other avenues. For what ?

Ludovik Slimak: All archaeologists say it: from 50-70,000 years ago, we observed technological changes at a breakneck pace. There is a before and an after. We even change the name to talk about these periods which last only a few millennia – which is very fast compared to before. Flints dated 48,000 years ago are no longer the same as those 46,000 years old, nor those 44,000 years old, etc. It’s so impressive that there was a desire to find an explanation in terms of a transformation in the body. This is why we have a privileged time track of a mutation of the FOXP2 gene [NDLR : appelé le gène du langage]which was believed to have occurred around this time. In his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humanity (Albin Michel), Yuval Noah Harari is part of this school of thought.

But we have since known that this lead is false. The FOXP2 mutation has been found in much older Homo Sapiens and even in Neanderthals, which did not experience such an abundance. No geneticist anymore supports this thesis today. Whether from the perspective of physical anthropology or genetics, we are the same old Sapiens as those of 50,000 or 150,000 years ago. However, archaeologically, there has been a change. Something enormous happened which means that the populations living at that time – and those of today – no longer have anything to do with those of 150,000 or 300,000 years ago.

Why were we so keen to look for a genetic explanation?

We have seen, in recent years, a sort of real takeover, I almost want to say a coup d’état of the hard sciences over the human sciences. This is a very Anglo-Saxon approach, and in particular American, which aims to understand Man based on his body, his genes. This had a very strong impact on the sciences aimed at studying Man by emphasizing the development of genetic analyzes and physical anthropology. For example, we have sought to understand Man by studying the morphology or structure of his bones and the shape of his skull, his genes, even the color of his skin, etc. However, it is not the analysis – even the most in-depth – of the morphology of a skull or of a gene that will allow us to understand what is happening in the head of a human population.

So why did Sapiens, apparently “asleep” for centuries, suddenly wake up?

What is interesting is that this upheaval is observed everywhere from 50-70,000 years ago, except in Australia with the Aboriginal populations. There were several populations of Sapiens in Australia and they all had one thing in common: the desire for continuity. For them, there is nothing more dear than doing the same, nothing more important than perpetuating the traditions of the elders. These are societies that are against time, or rather who do not want time to have an effect on them. All the archaeologists who work in Australia say it: there is nothing more monotonous than their excavation sites. They always find the same things or almost. And this is also what I see in my archaeological excavations among Neanderthals in Gibraltar or in the Rhône valley and that archaeologists observe in populations of Sapiens dating back 300,000 to 70,000 years.

“Sapiens is not his genes or his skin color, but what is in his head”

Among the Aborigines, this desire for continuity is a powerful imagination, as powerful as the desire to say: “I must innovate, I must build pyramids, cathedrals.” This may seem shocking, but it is nevertheless fundamental: Sapiens is in total disconnection with the realities of the world. What matters to him are the myths going on in his head. When we understand that it is imagination that structures human societies, we have a common thread. And when we unroll it, we see that the upheaval observed 50,000 years ago is accompanied by a deep desire for innovation and change. What I explain in my book is that Sapiens is not his genes or his skin color, but what is in his head. It is his imagination, it is his thoughts, from which he is inseparable.

So the big upheaval happened in our heads. But why at that time?

We don’t know, but we can put forward hypotheses. Let’s admit that for Sapiens societies in Africa and Asia the most important thing was to do the same, as among the Aborigines, and that at one point, human groups left the process of continuity and proposed something else. They have entered a mechanism where change is no longer taboo and where it has even become fundamental to invent new things, new technologies, to conquer new territories. It is likely that these companies had some success and that their changeover had a snowball effect. Because the societies which have escaped from “fixed imaginations” have necessarily had an impact in everyday life, in social, economic and technological structures, and we can therefore imagine that they have been attractive.

“There is a fear among Sapiens, a refusal of all otherness and all difference”

But when we are in a desire to “do better” and to invent, which are our current constructions, we are not superior to the old Sapiens, far from it. We must not rank these different societies by saying that one is superior to the other. Moreover, this change is not necessarily something that we have gained, because Homo Sapiens has rather lost its mythological vision of the world where everything must be the same. But objectively, there are modes of socio-economic organization which are more or less efficient and which have led us, after several centuries, into industrial systems.

You mention a “snowball” effect. Could it therefore have been enough for a single man, or a single tribe to change, for the others to imitate him?

This is the black sheep theory, which I develop in my previous books. There is this desire in Sapiens for everyone to do the same thing at the same time and even a near impossibility of doing things differently from others. There is a fear, a refusal of all otherness and all difference – moreover, I do not believe that we are more open to difference today than before. It’s an almost biological reaction.

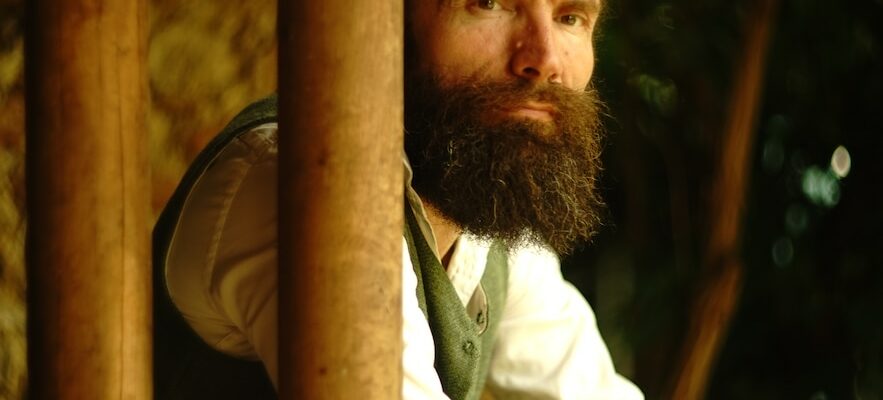

Ludovic Slimak, CNRS researcher at the University of Toulouse

© / Odile Jacob/Laure Metz for L’Express

But this particularity also carries its contradiction. This is the Sapiens paradox and the hope of the black sheep. Because if an individual has a different vision, he will of course be attacked, but if he has an impact on society thanks to his charisma, his intelligence, his success, and if his peers subsequently understand that his new proposal is interesting, so he can take everyone with him. Take Einstein, he was ostracized for twenty years, sometimes with extremely harsh words, before becoming an icon of a new way of thinking.

Why is it so important to understand Sapiens, to know who he is?

Today, sadly, there is a disinterest in who we are. How many people are really interested in Sapiens or Neanderthals in France: 20,000? I find it important. I challenged myself to try to get many more than 20,000 people interested in us. People must have a taste for knowledge, because it is available. And we need to make it clear why it’s fascinating. If we do not carry out this fundamental work, we will completely disconnect the scientific community from the community of people. The issues are there.

Naked sapiens: the first age of dreams (Odile Jacob, 352 pages, September 18, 2024)

.