After the difficult subjects tackled recently in this column: pedophilia in Romania, going beyond art with the situationists Guy-Ernest Debord and Gil Joseph Wolman, I feared the intoxication of the peaks and told myself that it would be wise to sober me up with a comic that is easy to understand and simple to explain.

In the genre, Eric Stalner imposed himself with his 1:17 p.m. in the life of Jonathan Lassiter (Big angle). The action takes place in the mid-1960s, in Keanway, a small town supposedly located in Nebraska. With his realistic drawing, in black and white full of shades of gray and a few streaks of blood red and lipstick, the author serves up a dish with all the ingredients of the genre: a young employee of a assurances who gets weighed down by his boss and his girlfriend. Leaving to get drunk in a bar, he meets the man who introduces him to life, that of the local underworld. And it’s the parade of well-documented commonplaces: the Standard Oil gas station, the big cars in pursuit, the tragic accident, the smoky jazz club full of curvy girls, the sublime singer, object of rivalry between the two bosses of the bled, the fat crooked and stupid cop, the sumptuous villa at the exit of the city which serves as a brothel, the friendship which is tied, more and more equivocal, between the two heroes, firearms, killers professionals, hysterical dogs, a terrace with a night view of this city riddled with corruption, a few drugs, whiskeys galore and lots of cash, hamburgers and coffee served by an courteous hostess, a motel, and finally: a small taste of why I waste my time reading remakes when I could find a hundred times better in any old Black Series? The plague of novelties.

A really funny “Tango”

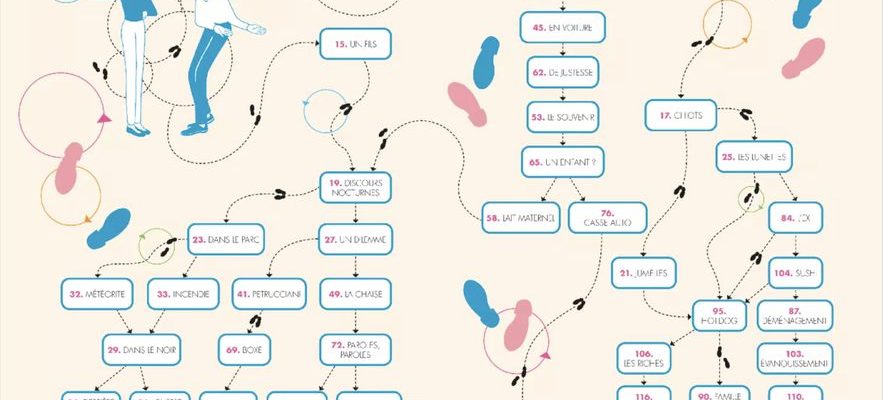

It is with much less scenery and more unforeseen events, fewer costumes, fewer characters, that Fulvio Risuleo and Antonio Pronostico treat us to a Tango (Blowgun) otherwise alert. A man and a woman, Lele and Miriam, argue all day for 234 pages, and they like it: “Look me in the eye when we fight!” At first sight intriguing with its minimalist line, it is further purified over the course of the chapters which are not because, very quickly, the authors claim to offer the reader the choice to change the course of history. For example, at the end of yet another shouting match, threatening final separation, they announce at the bottom of the page: “Lele catches up with Miriam, goes to page 34/Lele lets Miriam go, goes to page 36.”

“Tango”, by Antonio Pronostico (Artist) and Fulvio Risuleo (Scenario)

© / Sarbacane

At the time of their arrival on the children’s book market, I hated these bite-my-finger treasure hunts. Children’s literature was sufficiently tainted with demagogy that we did not add to the pseudo-ludic. Looks like I wasn’t the only one to protest, because publishers seem to have almost completely stopped using this unfair process to force kids to read… bullshit.

In fact, it is understood very quickly, the authors of Tango are on the right side of the deal. But unlike me, who gets on like milk on fire, they took the reviled process as a joke, even going so far as to use it as a recurring gag. Thus, when the reader is offered the choice of aborting the dog or taking the children to the zoo, inviting friends over for dinner or buying a house in the country, the footnotes send us to improbable consequences, so that we no longer know whether we should prefer that the bickering parents have a car accident or that they watch a documentary on the life of the quarreling lions.

What started out as a painful book to read becomes really funny. With a sumptuous finale: the visit of an apartment that the couple plans to buy, in a hurry to argue in this new home.