100% creation continues its special series around the professions which contributed to the construction of Notre-Dame de Paris. Today, we have an appointment with Édouard Cortès, apprentice ax carpenter or knacker. At the heart of the restoration of Notre-Dame de Paris, ax carpenters reused medieval techniques. This return to basics highlights ancestral know-how while meeting contemporary requirements.

For me, it was the ax cutting of a canoe that took me to the great nave, the flagship of Notre-Dame on the Île de la Cité.

Édouard Cortès, apprentice ax carpenter or knacker

Rendering is quite exhausting monastic work and sometimes you have to rest your muscles. We would do periods of a month or two, sometimes a few weeks and others would come and take over. For the carpenters and knackers, those who worked with axes, there were around forty of us taking turns. We were not permanently on the same site. We simply took turns for health reasons, to avoid exhaustion and also because it gave room for several carpenters with axes. There are several of us who have had this little privilege of being able to cut the beams of Notre-Dame.

Édouard Cortès was born in Paris. His life is marked by travel and discovery. His journey, rich in experience, has allowed him to develop a unique approach to woodworking. He built a wooden cabin in Périgord, then a wooden canoe, using an axe. Respect for nature and creativity led him to the construction site Notre-Dame of Paris. But Édouard Cortès also has a personal relationship with the cathedral.

“Is it a coincidence that I am on the Notre-Dame construction site? I have a little story with Notre-Dame: I proposed to my wife at kilometer zero on the square in front of Notre-Dame, and I left for Jerusalem on foot, I made a long journey and I left of Notre-Dame for this trip. I have always had an affection for Notre-Dame, as we all have an affection for Notre-Dame, and then even more so with the terror of the fire which revealed to us what this cathedral was precisely, not just a cathedral, but also a beating heart. And there, it was a burned heart. Today, seeing the building, the restoration, the great vessel, the great Parisian cradle which is reborn from its ashes, I say to myself : “The burned heart is now a burning heart.” So, I don’t really know where I am in my faith, but in any case, I am happy to see that at Notre-Dame there is a new heart beating. »

Édouard Cortès is one of the forty carpenters who worked with an ax to identically remake the framework of Notre-Dame de Paris.

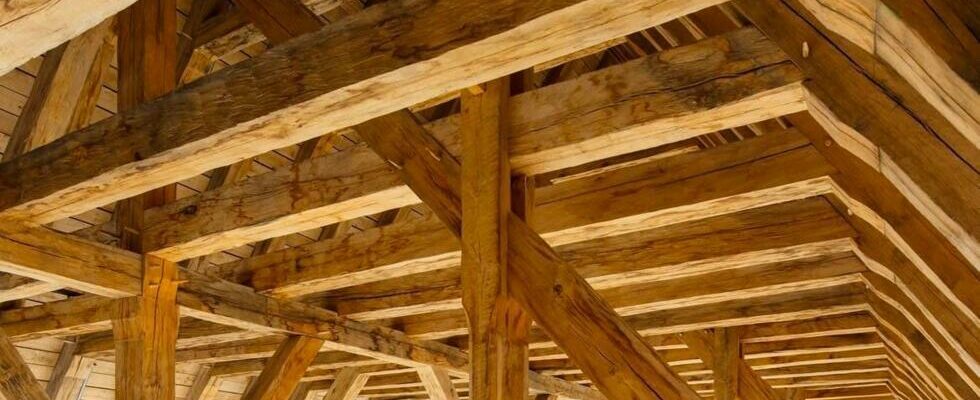

“The squaring technique is a medieval technique, we work on green wood. In the workshop, the logs, these tree trunks which are freed from their branches, are placed on trestles and then the knacker’s work begins. We seek to keep the shape of the tree for mechanical reasons, therefore to follow the grain of the wood. We do our marking and work with several types of axes. Once the shape is identified, we make our markings with red and black, remove the bark and then we work with different types of axes, different types of axes. First, big hammers, there we climb on the tree trunk, we stand to remove large pieces of wood, large scraps, large splinters. And there you have to go. Then, we take the doloire, this ax which is a little off-center, which has only one bevel, only one cutting edge, and with the doloire, we scrape lightly, we remove a thin layer, sometimes shavings to refine and that’s what gives that finish. When you see a beam with its little waves, called cupules, which leave the mark of the tool and which leave a little hollow. »

The restoration of Notre-Dame de Paris used the doloire, an ancient carpenter’s axe.

“The sorrow has been our tool, like the warrior to his weapon, or like the painter his brush, the writer his pen. We are in pain. It comes from Latin painit’s suffering, pain, so yes, there was a constant effort. When you are squaring a long beam at the doloire, this specific axe, well, you have to be persistent. There is a form of inner music. You have great length. If you make a twelve meter rafter, you know you have it all day. You move forward little by little. It’s like walking, it’s slow, but you have a goal. And in the evening, when you look at your beam, you say to yourself : “Ah! I finished my beam. Incredible! In one day, I managed to free a beam. And I know where it will go in the framework of Notre-Dame.” So, you are happiest with the artisans and you are close to the artist because your work is accomplished. You have made a little masterpiece. You don’t sign your masterpiece. This is perhaps what distinguishes the artisan from the artist. In any case, you only mark yourself sometimes with a little blood, when you burst your hands, which mix with the tannin, with sweat, that’s for sure. But you just left a little trace of the axe, a little trace of the pain. This is what we carpenters will leave up there: the traces of our sorrows. »

The reconstruction of Notre-Dame de Paris presented many challenges, ranging from construction techniques to time management. Difficult working conditions meant respecting the architectural heritage of the cathedral while maintaining a high level of quality.

“The big challenge was to imagine these deadlines, to do very well with very little time. Impossible is not French, it’s impressive. When there is a will – there was money, obviously, we must salute the 340,000 donors, from small to large donors, we must salute this financial power which enabled the resurrection of Notre-Dame -, a will, quite strong, and a common goal, and then a camaraderie, a humanity in everyone. We tried to be good, not only in our work, but also in reporting. We knew that the site would be exceptional, that the pressure that was put on everyone, from the smallest to the largest in the hierarchical dimension of the site, we knew that this pressure would be difficult for deadlines. I think we lived up to that pressure because we were good. Obviously, there were snags, arguments, lots of constraints. Stone, wood, lead, glass constrain us. But I believe that beyond the beautiful work, we tried to create a beautiful human work. A sort of cathedral of companions. Despite the differences where we came from, who we were, what we wanted in this project, despite all that, we were just as good and we also did great work between us. »

This extraordinary project changed the life of Édouard Cortès, an ax carpenter.

“This great misfortune made us rediscover the memory of our country. We could have made a glass spire. No, we did an ancestral gesture again. The most beautiful contemporary gesture that has been made is to remember our elders and to say to ourselves, there is a very small gesture to the doloire that was made and which allowed a green wooden frame to last over 850 years old. Let’s do it again like our elders, let’s redo beautiful work so that it lasts another 1 000 years. When you cross the great forest, the great height, there is an emotion. It vibrates, it’s beautiful, it’s aesthetic and what’s more it’s solid and it’s undoubtedly there for 1 000 more years. »

Find all the episodes of 100% Création on:

Apple Podcast Castbox Deezer Google Podcast Addict Podcast Spotify or any other platform via the RSS feed.

Also readGuillaume Bardet and the liturgical furniture of Notre-Dame de Paris [7/9]