“Alea jacta est. The National Assembly has approved the bill on abortion”, we can read in the pages of “Madame Express” of December 1974. In its septuagenarian history, L’Express has supported numerous battles. That of women’s right to abortion is a central one. On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the promulgation of the Veil law, on January 17, 1975, let us look back at the way in which we treated this historic event.

Even before Simone Veil defended her bill in the National Assembly, L’Express was already raising the thorny issue of abortion. We have to go back to April 1974. The death of Georges Pompidou “caused all the files to be put away in the safes and cupboards”, lamented the journalists Albert du Roy and Françoise Monier, and in particular the Taittinger-Poniatowski law, the first project to legalize abortion. “No reform was more urgent: there are more than seven hundred thousand clandestine abortions per year,” they recalled bitterly.

Simone Veil on the cover of L’Express on the eve of her speech to the National Assembly on abortion.

© / The Express

A bill carried by a woman

In May 1974, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing came to power. The new president, whose legalization of voluntary termination of pregnancy (abortion) was a campaign promise, is giving new impetus to the bill. He appoints Simone Veil to bring it before the deputies. A strong sign recognized by L’Express, which underlines the fact that such a file was entrusted to the Minister of Health and not to that of Justice, but also that it was entrusted to a woman: “It is first of all a way of showing that the new law should not be repressive but that it must, on the contrary, emphasize the health, physical and moral, of women. not bad as a woman […] confronts the mass of deputies who are indifferent to women’s issues – when they do not ‘revulse’ them”, ironically underline Catherine Nay and Michèle Cotta.

In an editorial from June 1974, Françoise Giroud, then editorial director of L’Express – a position she left a month later – and Secretary of State for the Status of Women in the Chirac government, called for a new bill on abortion “before the end of the year”. She highlights the gap between the reality of women who resort to clandestine abortions and that of those who oppose their legalization: “Since medical progress makes it possible to prevent conception, to safely avoid a untimely birth, […] the “trapped” woman feels like the victim of an intolerable injustice.”

A gap which will always be denounced in L’Express. In November 1974, Catherine Nay and Jacques Perrier wrote: “We should not be mistaken about the number of opponents, even noisy ones. In this case, the silent majority is for putting an end to the abortion scandal clandestine.”

The issue of abortion becomes political

Catherine Nay and Jacques Perrier regret that the liberalization of abortion, originally a social problem, is transformed into a “political equation”: the majority deputies are “all scared” of losing their voters, they reported, quoting a parliamentarian from the Union of Democrats for the Republic (UDR, ancestor of the Republicans). “Who wants to say and write to their MP: ‘I am for abortion’? We are never for it. We resign ourselves to it”, defended the journalists.

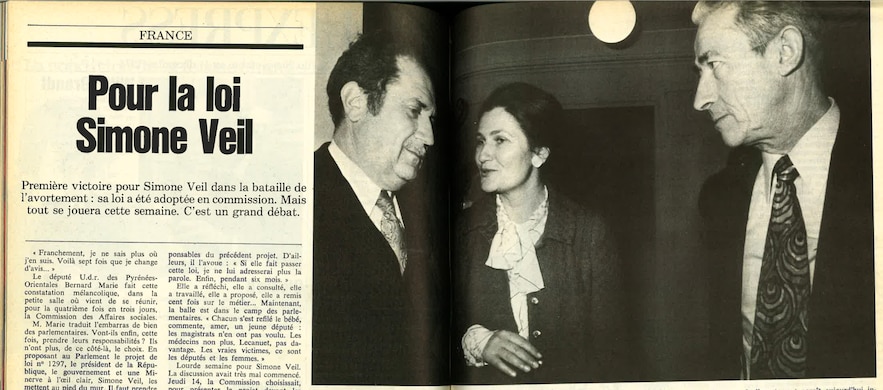

Michèle Cotta and Catherine Nay published an article entitled “For the Simone Veil law” in L’Express in November 1974.

© / The Express

Alexandre Bolo, UDR deputy for Loire-Atlantique and rapporteur of the law, is himself opposed to the liberalization of abortion. “It is to this declared adversary that Ms. Simone Veil, the Minister of Health, had to entrust the fate of her project”, deplore Catherine Nay and Michèle Cotta in an issue of L’Express entitled “For the Veil law” in November 1974. The two women underline the existing opposition between the bill carried by Giscard d’Estaing through his Minister of Health and his own UDR deputies.

A few weeks before Simone Veil’s historic speech at the National Assembly, they call on the presidential majority, “up against the wall”, to take responsibility: “Change is here […] in the necessary adjustment of the law on morals rather than in blindness.” “The failure of the bill in Parliament would be a failure of Giscard”, consider the two women.

Difficult installation

The Veil law was finally promulgated on January 17, 1975, for a probationary period of five years. Women can now legally have an abortion before the end of the tenth week of pregnancy in approved hospitals and clinics. But its implementation turns out to be complicated. Some doctors refuse to perform abortions, others are reluctant to do so due to lack of preparation: “When we pass a law, we have to ensure that stewardship follows. My department is overflowing,” testifies a doctor. In May 1975, four months after the law was put in place, Simone Veil spoke in L’Express: “There are laws which apply themselves. The law on termination of pregnancy n “It’s not one of those because its purpose is not to structure a profession or organize services: it disrupts morals”, she confides to Michèle Cotta.

In the rest of her interview, Michèle Cotta regrets that a fight in which L’Express has always been a driving force has been put aside with this spotlight on abortion. That of contraception. The Minister of Health responds by recalling how important it is to educate women on this subject: “We must [leur] say: if you do not want other children, if you want to plan the births of your children, it is through contraception and not through the termination of pregnancy that you achieve this.” The Veil law will be definitively renewed on November 30, 1979.