Fans of Korean dramas have been served. Between the proclamation of martial law, the anger in the streets and the arrest of President Yoon Suk-yeol this Wednesday, January 15, Korean politics has, in recent weeks, taken on the appearance of a television soap opera. Behind the institutional crisis, the economy also suffered some shocks during December: the stock market swayed, the Korean won reached its lowest against the dollar in almost sixteen years, and annual inflation rebounded.

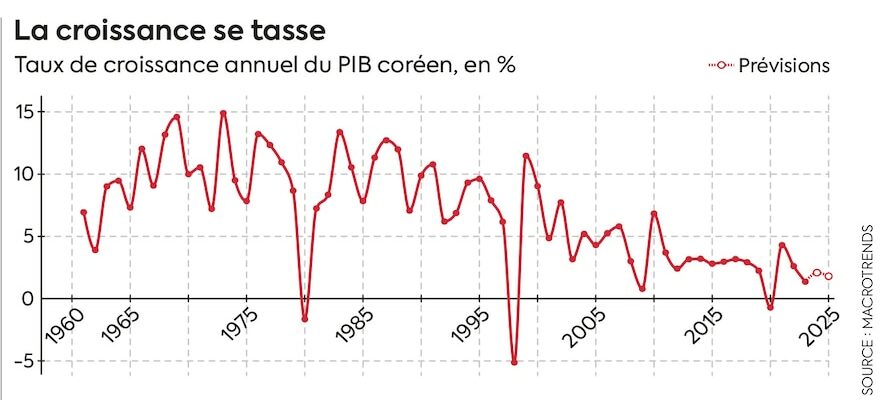

Added to this economic storm are signs of a deeper malaise. Growth forecasts have been revised downwards. The government now expects 1.8% for 2025, after 2.1% in 2024, citing “significant challenges for the Korean economy”. The double-digit growth that has long carried the “Miracle of the Han River” seems far away.

Since the 1960s, the country of Morning Calm has experienced a spectacular trajectory. Going from the rank of a marginal economy – ravaged by poverty and bearing the scars of a devastating war – to the circle of Asian dragons, it left its northern neighbor far behind. The secrets of this ascent? International openness, strong investment in innovation led by a strategic State, and support from the United States. The Asian crisis of 1997 shook this foundation, leading to the bankruptcy of several Korean flagships, but the economic fundamentals remained solid. The pace of the economic boom moderated as Korea found its place in the club of developed countries.

Looking towards the world

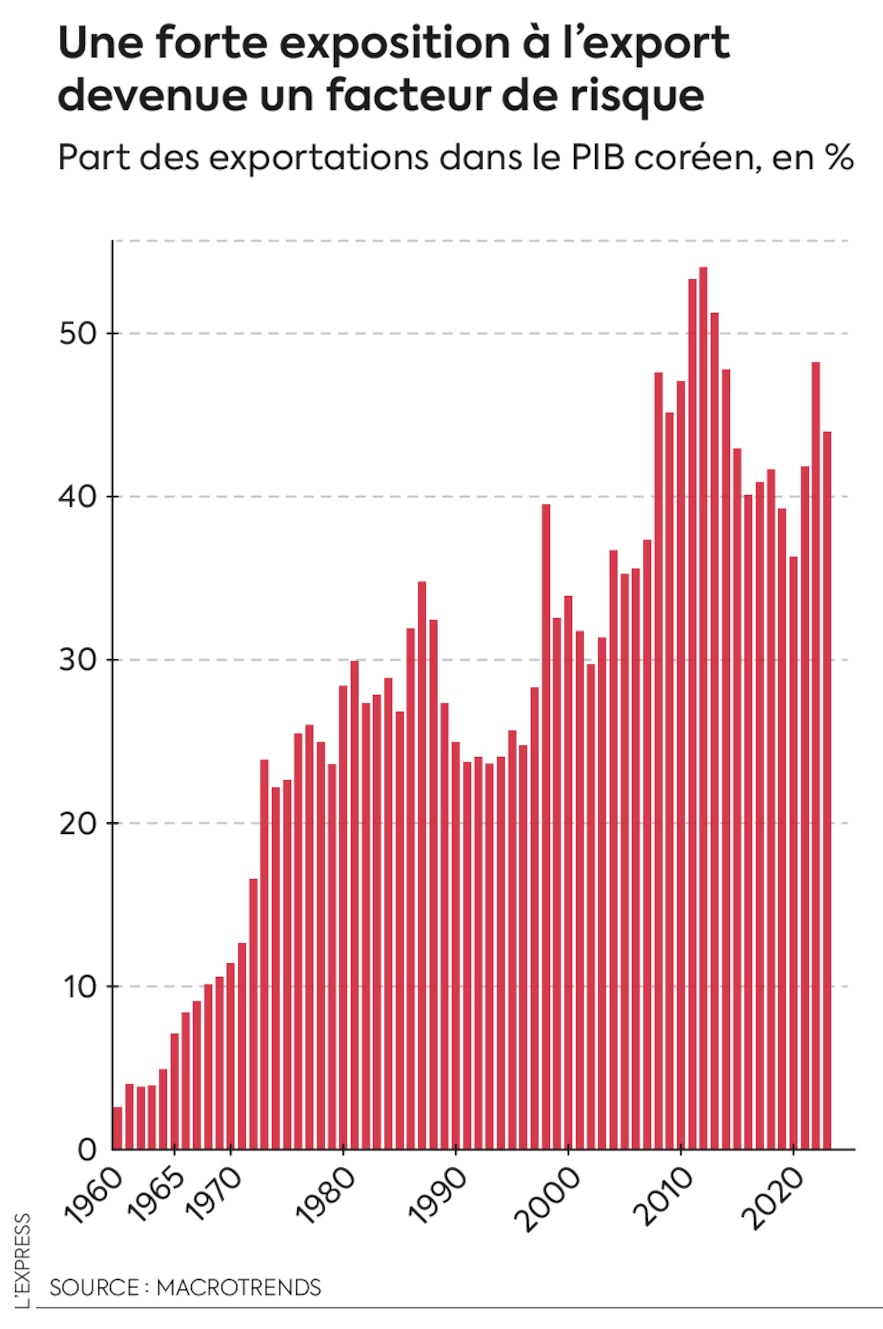

During all these years, export has remained the alpha and omega of the Korean model. Beyond automobiles and electronic devices, the country has made its soft power. Hallyu [NDLR : vague culturelle coréenne] has spread national pride throughout the world like the series Squid Game or the K-pop boy band BTS. The success of the latter is such that its annual contribution to Korean GDP was estimated at around 0.3% by the Hyundai Research Institute in a 2018 report.

In South Korea, growth is slowing down.

© / The Express

Problem: the drivers of Korean performance have changed little. “Korea is now vulnerable in some areas where it has excelled in recent decades. Semiconductor companies failed to grasp the scale of the artificial intelligence market in time,” notes Daniel Tudor, author of Korea: The Impossible Country. A sector which remains dominated by the American Nvidia. However, the Korean giants, on the lookout, are still competitive. “The semiconductor race is […] a total war between nations,” declared deposed President Yoon Suk-yeol last April.

Meanwhile, China is gaining ground in Korea’s preferred sectors – steel, electronics and shipbuilding. In the automobile sector too, competition is tough: “A few years ago the taxis in Beijing were all Hyundais. Today, they are BAICs [NDLR : Beijing Automotive]”, observes Rory Green, director of Asian research at Global Data.

Seoul is aware of these challenges and is working to address them. “To diversify its growth drivers, Korea is working to make artificial intelligence, biotechnology and quantum information “game changers’. The government plans to develop innovative strategies to promote these industries,” Moon Seoung-hyun, the South Korean ambassador to France, told L’Express.

The protectionist temptation of the United States, which recently became the country’s leading trading partner, is another source of concern. “In a sense, Korea is similar to Germany: being very good at exporting is a strength in conquering foreign markets. But if these markets close, it becomes a handicap,” judges Sylvain Bersinger, chief economist at Asteres. National political uncertainty only exacerbates the problem. “If Korea does not have a strong executive in the coming months, at a time when the Trump administration risks imposing tariff barriers, will it have a strong enough voice to lead trade negotiations with the United States?” asks Françoise Huang, Asia-Pacific economist at Allianz Trade.

Family capitalism

Inside the country, the challenges are just as great. The Korean economy is largely dependent on “chaebols” – family conglomerates closely linked to power. Dynasties like that of the Koos, at the head of LG, or even the Lee, at Samsung, have ruled their respective empires for decades. The porous border between the world of business and politics has also given rise to some scandals.

Strong export exposure.

© / The Express

For Yeo Han-koo, former Minister of Commerce of South Korea and expert at the Peterson Institute, the control of these large groups is a brake on economic dynamism. “This domination stifles the emergence of new innovative companies and kills innovation. Ten or twenty years ago, the ten largest companies were almost the same as today. This shows that the system is not enough flexible to allow small businesses to become the giants of tomorrow”, he regrets.

Giants are increasingly tempted to strengthen themselves abroad, to the detriment of the local economy. “Rising costs in Korea and numerous regulations are pushing international companies to flee the Korean market and invest in the United States, the European Union or Southeast Asia,” continues Yeo Han-koo.

Demographic challenge

To train its future workers, Korea can count on an education system based on excellence and competition. But the other side of the coin is worrying: the suicide rate is one of the highest in the world. “There is a social and moral crisis in the background of the political crisis. Stress and the race for performance certainly partly explain it,” summarizes Dominique Barjot, professor emeritus of contemporary economic history at Sorbonne University. Korean growth is a dynamic of despair. Its principle can be summed up simply: you have to be the best to survive.

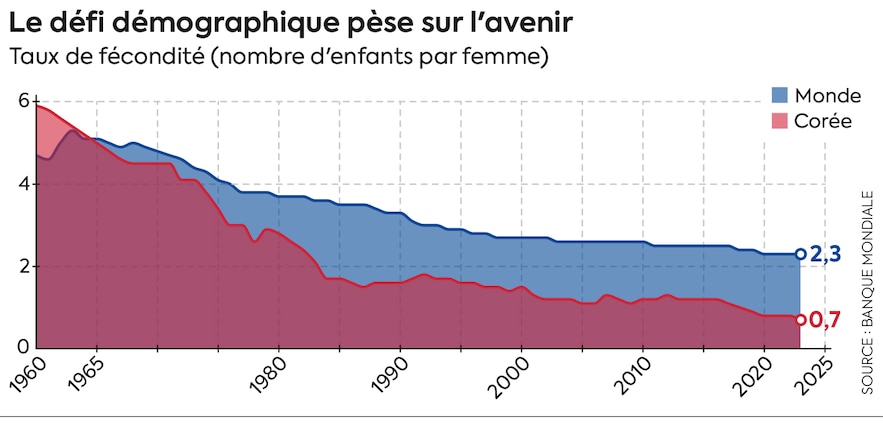

The demographic challenge weighs on the future.

© / The Express

The demographic question is also becoming worrying. To the point of weighing on long-term growth, which could fall to 0.5% in 2050 according to experts from the Korea Development Institute. At 0.7 children per woman in 2023, the fertility rate is the lowest in the world. The Booyoung construction group offers some 100 million won (70,000 euros) to its employees who become parents. “The Korean state has long neglected the lever of immigration to fight against demographic collapse, focusing on an increase in births. This has not given the hoped-for results,” notes Rory Green, of Global Data.

At the same time, the aging of the population reduces the working population and increases labor costs. “Today, there are more elderly people in companies, and in a very Confucian country, it is obligatory to pay them more,” notes Dominique Barjot.

Despite this slowdown, Korea does not admit defeat. In addition to measures to attract foreign talent, “the Korean government is actively implementing policies aimed at reconciling work and family life, in order to increase the birth rate,” says Ambassador Moon Seoung-hyun. There is urgency.

.