Tails, a pandemic. Heads, the threat disappears. The coin is tossed into the air, and it is very clever who could predict which way it will land. The H5N1 avian influenza virus circulates extensively in animals – wild or domestic birds and mammals, and especially in cattle herds in the United States. Its incursions in humans reach levels rarely seen, with 66 cases in 2024 across the Atlantic, including two serious ones, and a first death in early January. If these are sporadic infections, the fear that this new enemy will eventually become transmissible in our species is on everyone’s mind.

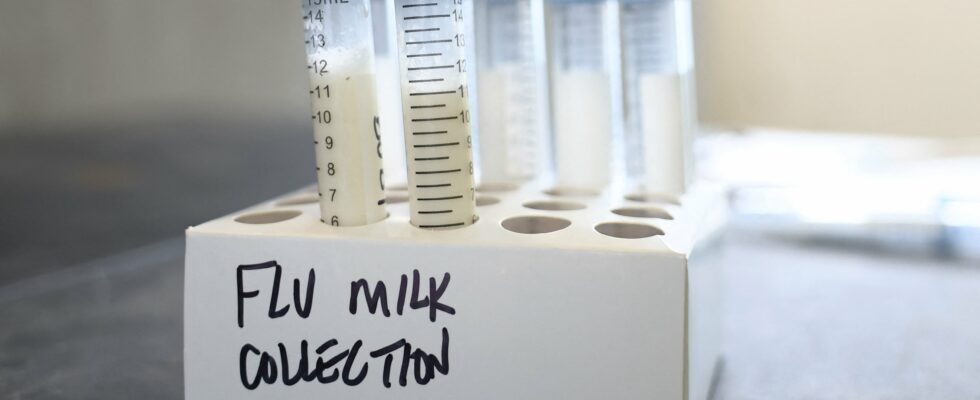

Totally unpredictable, influenza viruses nevertheless remain formidable and feared. This one in particular, and in particular its version found in birds: since its emergence in chicken farms in Hong Kong in 1997, it has killed 30% to 50% of infected humans, fortunately few in number. The first American death was also contaminated by a wild bird. Its variant detected on cattle farms has adapted to the udders of cows – it seems to be transmitted primarily through contact with contaminated milk, and has so far only caused mild cases. “At this stage, the alert level remains low, but the situation is considered sufficiently critical by health authorities around the world for preparation to be launched,” summarizes Professor Brigitte Autran, president of Covars, the health risk monitoring and anticipation committee.

Overreaction after the destitution of the planet in the face of Sars-CoV-2? Still, against H5N1, our arsenal seems better stocked. Vaccines, first of all, are in development. Seasonal injections would in fact be of no use: suitable products will be needed, which are more complex to produce. Usually, manufacturers inject the circulating viral strain into millions of eggs, where the virus multiplies before being extracted and then inactivated. Impossible with an H5N1. “As this virus is highly pathogenic for poultry, it would also be for eggs. The viral strain must therefore be genetically modified upstream, to make it less dangerous and allow it to multiply in eggs,” explains Professor Marie -Anne Rameix-Welti, head of the National Reference Center for Respiratory Infections, at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Vaccines: still bottlenecks

The preparation of these adapted viral strains falls under the competence of the World Health Organization (WHO). The UN institution even already has an entire catalog. Twice a year, at the same time as they choose the strains to be included in seasonal vaccines, its experts identify potentially threatening zoonotic viruses in nature, for which it seems important to have modified “ready-to-use” vaccine strains. “. These are produced by partner centers of the international organization, like the American CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). “Tests with the H5N1 viruses circulating in the United States showed that two of the modified strains already available would offer protection,” said Margaret Harris, WHO spokesperson. If necessary, they would be made available to manufacturers so that they can manufacture the injections. Enough to save a few weeks.

A valuable advance, because although the classic technique for producing influenza vaccines on eggs is well established, it does not allow for great reactivity or an exponential multiplication of volumes. “By definition, you need eggs, lots of eggs, and eggs of a particular nature, since they are ’embryonated’: nothing to do with those found in stores,” recalls Marie-Paule Kieny, virologist and former president of the Covid-19 vaccine scientific committee. Manufacturers order them once or twice a year, when they start manufacturing doses against seasonal flu. If the alert occurred just before the start of production, it could be redirected, but later, the eggs would no longer be available: you would have to wait to obtain them again.

Another bottleneck identified by the WHO in an as yet unpublished report concerns “fill and finish”: the stage of filling the vials. Current capacities, considered insufficient, could also limit production. “Clinical trials had also shown that it would take two doses to obtain a good level of protection, compared to just one for seasonal flu. By reorienting all available production lines, it is probably quite realistic to think that we would achieve to vaccinate 1.5 billion people in one year”, estimates Marie-Paule Kieny.

Enormous, but insufficient to quickly protect the entire planet. As with Covid, would messenger RNA technology save us? To date, no influenza vaccine based on this platform has been marketed. But developments are progressing well. The American firm Moderna announced in June that its combined Covid-seasonal flu vaccine triggered a good immune response. An essential milestone, first proof that messenger RNA could work against viruses influenza. Since then, Moderna and the American CDC published in mid-December a study in the prestigious journal Science showing that an H5N1 messenger RNA vaccine was effective in protecting ferrets, the preferred animal model for respiratory infections. Pfizer, GSK and American academic teams are also in the running.

The race for control is on

The big question will then be obtaining the injections – we remember the battles between States during the Covid pandemic… Some countries already have stocks adapted to previous strains of avian flu. “They would not necessarily be useless: the unexpired vials could be used as first doses,” indicates Professor Marie-Anne Rameix-Welti. The fact remains that the race to order suitable vaccines is already underway. The United States has purchased a total of 10 million doses from three producers. As in the Covid era, the American government has also committed to financing the final stages of the development of Moderna’s vaccine. Enough to then guarantee privileged access to its production. The Europeans, for their part, are expecting a delivery of 665,000 doses, and have signed a purchase option for 40 million vaccines. from the manufacturer Seqirus. “France has reserved several tens of thousands. This small stock would make it possible to vaccinate in a ring around possible cases of human contamination in a farm for example,” explains virologist Bruno Lina, also a member of Covars.

Furthermore, the WHO has already concluded agreements with the main manufacturers: they undertake to give it the equivalent of 10% of their production, intended for developing countries. Above all, technology transfers are organized under the aegis of an organization associated with the WHO, the Medicine Patent Pool (MPP): “We work with laboratories located in 14 low- or middle-income countries, so that they have the capacity to produce messenger RNA vaccines for their population”, explains Marie-Paule Kieny, today head of the MPP. The fact remains that in the event of human-to-human circulation of an avian flu virus, we would not escape barrier measures until the vaccines arrive.

In the meantime, however, we would have two other weapons that were so lacking five years ago: medicines and tests. On the antiviral side, France has 200 million Tamiflu tablets. A volume deemed sufficient by the High Council of Public Health in a report published in December. This body also calls for an extension to twenty years of the expiry dates of this product, like the choice made by the United States. Covars also recommended that the State prepare stocks of another antiviral, baloxavir. “Its effectiveness seems greater than that of Tamiflu,” explains Professor Autran. “Our message has been heard: Europe has made a pre-commitment to purchase from the manufacturers.”

Insufficient measures to curb the virus

The tests are already being deployed. “The PCR tests used in France for the diagnosis of human influenza also make it possible to identify H5N1 avian viruses similar to those circulating in the USA,” explains Bruno Lina, who directs the National Reference Center for Respiratory Viruses based in Lyon. If one of them was detected, the network of specialized Biotox-Piratox laboratories will soon be able to carry out more specific tests, and in the event of proven H5N1, the two reference centers, in Paris and Lyon, would be alerted. and would intervene to isolate the patient and limit transmission. “In terms of preparation, we are in a very favorable situation. The current alerts have made it possible to put ourselves in battle order. Hoping that we will not need it,” summarizes Professor Antoine Flahault, director of the Institute of global health at the University of Geneva (Switzerland).

This is the paradox, with on the one hand preparations well advanced, but on the other measures long insufficient in the United States to slow down the circulation of the virus. “What we are witnessing is quite scandalous, with little transparency and late decisions to protect farms and monitor raw milk, when we know that it can promote transmission to humans,” laments Marie- Paule Kieny. The arrival of Robert F. Kennedy Jr, anti-vax and fervent supporter of raw milk, at the head of the American Department of Health is not reassuring. “The more we allow the virus to circulate, the greater the risk that it becomes transmissible. Moreover, markers of adaptation to humans appear as soon as it passes into a mammal or a human,” notes the Professor Rameix-Welti.

Since the controversial work of Dutch virologist Ron Fouchier, who made H5N1 transmissible among mammals in the 2000s, we have known the mutations that this microbe must accumulate to be able to circulate between humans. “There are at least five of them,” recalls Professor Lina. Like so many locks, which today prevent it from clinging to our cells, from multiplying there, but also from surviving in the air. “We have been fearing these changes for twenty-five years, and we have not seen them appear,” notes Antoine Flahault. Influenza viruses, however, have the particularity of being able to both evolve over time, by acquiring mutations one after the other, but also all at once, by exchange of genetic material with other viruses. Which direction will H5N1 choose? For now, the coin is still up in the air.