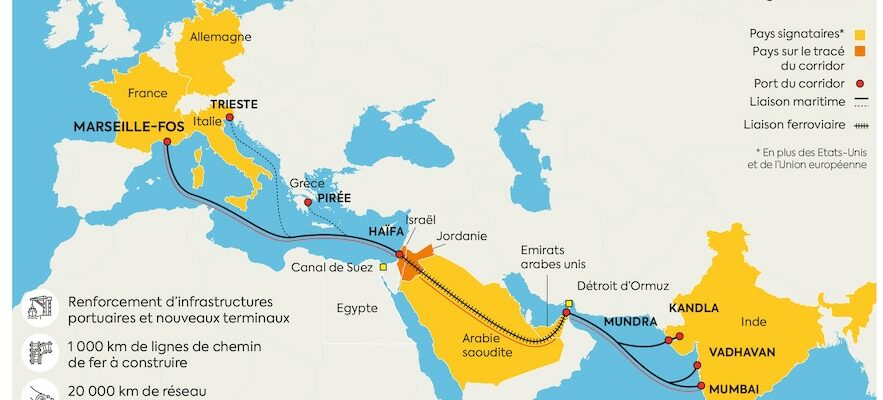

In an annex of the Quai d’Orsay, one rainy evening in December, Gérard Mestrallet speaks to around twenty business leaders. Accustomed to the exercise, the former CEO of Suez delivers a rehearsed speech, with a map to back it up. On the latter, we can see a route linking the Indian ports of Mundra and Mumbai to that of Marseille, and a title, in four letters: Imec. This Anglo-Saxon acronym, for India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (India Middle East Europe Economic Corridor), is a trade route project born a little over a year ago on the sidelines of the G20 summit in New Delhi. His goal? Facilitate the transport of goods between the three zones thanks to a maritime and rail network of more than 4,800 kilometers. A revisited version of the legendary route to India. The signatories are the United States, France, Italy, Germany, the European Union, India, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

To give substance to this titanic plan, it was Emmanuel Macron himself who mandated Gérard Mestrallet. And, as no other country has yet designated an official representative, the latter finds itself the de facto architect of the project. Converted into a diplomat, the 75-year-old former boss took the mission head on. For almost a year, he has been shaking hands with ambassadors, members of American think tanks and Indian port officials. “This corridor is not just a railway and pipes. It is important that it irrigate the areas crossed,” assures Gérard Mestrallet during a stopover in Paris between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

Planned route of the corridor

© / The Express

Momentum broken by the attacks of October 7

On paper, the project does not lack assets. Offering an alternative route to the Red Sea, undermined by the threat of the Houthis, it focuses on connectivity in the transport of goods, energy and data, thanks to a vast network of optical fiber and pipelines.

At the heart of this diplomatic puzzle, everyone follows their own score. Courted by the West, India is seeing new markets opening up to it. Europe, the way to diversify its value chains. For the United States, Imec is an instrument to circumvent China, a response to the new Silk Roads. Israel, which has not officially signed the agreement, also wants to be part of it. “Imec must see the light of day. For this, leaders must find the right financial incentives,” insists a person familiar with the issue in the Jewish state. The Gulf countries want to diversify their exports beyond the oil sector. The only downside: some of them play both sides with Beijing, also letting themselves be tempted by participation in the Chinese corridor. A ubiquity which does not worry Gérard Mestrallet, convinced that this is a guarantee of stability for the region. “It can be positive to have non-aligned countries, like the Emirates or Saudi Arabia, which do not choose one camp or the other,” he confides to L’Express.

So much for the theoretical diagram. But the reality is quite different. The attacks of October 7, 2023 in Israel and the outbreak of war in Gaza occurred a few weeks after the signing of the agreement. The planned progress meetings were canceled, leaving Imec to progress through bilateral meetings. And plans for the rail section, supposed to cross the Arabian Peninsula to the Israeli port of Haifa, have been put on hold. Delays are not uncommon in this type of initiative: the Gulf Railway, a railway project crossing six Gulf countries, announced in 2009, has not yet seen the light of day. “It is not necessary for all sections to progress in a uniform manner,” says Gérard Mestrallet. “We can imagine that Indian and Gulf ports are progressing more quickly, which is the case.”

While the Middle East is on fire, India is stepping up the pace. In September, it signed an agreement with the United Arab Emirates for a “virtual corridor” intended to streamline their trade. In 2022, the two countries had already committed to increasing their bilateral trade to $100 billion in the next five years. At the same time, New Delhi is continuing negotiations for its free trade agreement with Europe, which have been going on for almost twenty years. “India is more interested than before, after having long neglected its relationship with the EU, mainly for geopolitical reasons,” points out Olivier Da Lage, associate researcher at the Institute of International and Strategic Relations (Iris).

The most populous country on the planet is gradually placing its pawns. Gautam Adani, an oligarch close to power, manages the port of Haifa, in addition to that of Mundra – two essential nodes of the corridor. His group has also joined forces with TotalEnergies in a gigantic green hydrogen production project. An initiative that comes at just the right time, as hydrogen should constitute the keystone of Imec. Enough to delight Europe, which has set colossal objectives in this area – some 20 million tonnes of green hydrogen consumed in 2030 – and which is looking for suppliers.

Demonstrate your credibility

For his part, Gérard Mestrallet is preparing the ground for the post-ceasefire in the Middle East. With the hope that this new commercial route contributes to the normalization of the region, in line with the Abraham Accords of 2020. The partnership between the major maritime port of Marseille (GPMM) and its Saudi counterpart Mawani signed last June features the Imec stamp. “These cooperation agreements make it possible to build the corridor more quickly than intergovernmental approaches,” notes Hervé Martel, head of the port of Marseille-Fos. “There is a gap between geostrategy and logistics.”

At Orange, Nexans or EDF, Imec is far from being one of the priorities. TotalEnergies sees this as a “very long-term” project. In the Quai d’Orsay room, the doubt is palpable. “How do you plan to transport the hydrogen along Saudi Arabia to Haifa?” asks a participant. “You have to love adventure,” laughs another.

French companies are awaiting more details. Beyond the latent security risk, practical questions arise. How much time and money will be saved? Estimates differ: according to calculations by Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Imec will reduce transport time between India and Europe by three to six days. Other sources put it at two days maximum. Transfer points between ships and trains also pose a real challenge. “For the moment, it is possible that these load breaks represent additional delays compared to a passage through the Suez Canal”, remarks Laurent Livolsi, professor of management sciences at Aix-Marseille University and specialist in the issues logistics.

The vagueness on governance and financing does not help. Apart from Saudi Arabia, which has promised some $20 billion, few quantitative announcements have been made. On the European side, hopes are focused on the “Global Gateway” program, which promotes connectivity across the world, with a budget of 300 billion euros. But access to these funds is not yet guaranteed. “This project is a diplomatic narrative from the Biden administration to counter that of the Chinese Silk Roads, more than a real promise of investments,” says Jean-Loup Samaan, associate expert on the Middle East at the Institute Montaigne.

Launch studies, survey the market, specify the routes: everything still remains to be done. And, above all, set a schedule. “Even if the conflict in the Middle East ends, the project will take at least a decade to complete,” estimates Olivier Da Lage. Omens about which Gérard Mestrallet prefers to ironically: “If we listened to the American administration, everything would have to be completed in four years, the time of a presidential mandate. Imec is necessarily part of the long term.”

.