Boris watches nervously, often lighting cigarettes, as the workers on his farm disassemble and repair the doubling machine.

“I’ve decided to harvest because I have to pay the salaries of my workers and the money of the people I rent this land to,” says Boris, who doesn’t want us to use his last name.

While Ukraine’s Black Sea region of Odessa has not seen much conflict so far, nothing is guaranteed.

Russian troops have captured the city of Kherson, 200 kilometers to the east, and the Russian Navy is believed to have up to 30 warships in Black Sea waters with which they can launch missiles and land.

38-year-old Boris sent his wife and two sons abroad for fear of invasion.

He stayed behind to run the farm during the war. As he opens his large warehouse the size of two or three football fields, it shows how hard his job is.

There are about 1000 tons of sunflower seeds used in oil production in the warehouse. Ukraine is the first country in the world to export oil from seeds.

But now Boris cannot sell his harvest. “The Black Sea is closed and there is no way to sell the products. Existing sales channels offer very low prices and are not profitable,” he says.

Boris says that if he can’t sell his sunflower seeds within 18 months, they will rot on the farm. It’s a brutal irony as people around the world struggle to get food on their tables.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine at the end of February had a knock-on effect on global food prices.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations announced that vegetable oil prices increased by 23 percent, wheat prices by 20 percent and corn prices by 19.1 percent in March.

Ukraine and Russia are the main exporters of these foods. Prices had been on the rise before the war as the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted supply chains and bad weather affected yields. With the war, the burden of families became even heavier.

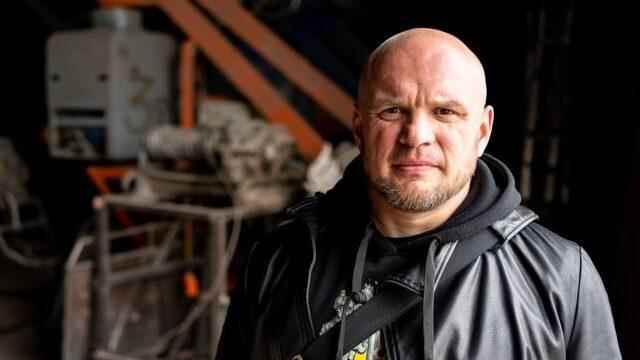

I met Roman Skyba in Chernomosk, an hour’s drive from Odessa. With his shaved head, beard, and leather jacket, he can be seen in trendy bars and restaurants around the world. His job, perhaps, is to provide the food supply for your favorite restaurant.

“Normally we used to send grains, corn, wheat,” he says, pointing to the nearly empty warehouses:

“There are between 12 and 14 ships anchored in the port of Chernomorsk. There are approximately 400 thousand tons of grain on these ships. Countries that are required to buy these goods as per the contract will not be able to.”

The grain in Skyba’s warehouses already had grain destined to go to Egypt, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, which are affected by the rise in food prices.

Along the Black Sea coast, Russia is blockading and millions of tons of grain cannot leave the ports.

Both countries accuse each other of mining the waters. This situation makes it dangerous not only for Russian and Ukrainian flagged ships, but also for ships of neighboring countries to navigate in these waters.

But what if the war ends soon? How quickly do food shoppers around the world experience relief?

Mikola Gorbachev, President of the Ukrainian Grain Union, which represents 40 large export companies, says, “We have sufficient stocks at the moment. About 20 million tons of grain. Since the grain infrastructure is not damaged, we can export them immediately.”

But Gorbachev is worried that if the war continues, many farmers may survive only one more harvest season and then go bankrupt and cease their activities. If this scenario happens, it will be much more difficult to restart global trade.

The Grain Union expects the next harvest to be 40 percent less than the previous one, with the important grain producing areas Mikolayiv, Kherson and Zaporijna under Russian occupation.

“In some areas, farmers won’t be able to go to their fields, there are too many mines that the military will have to neutralize. We will see yield declines because there is not enough fertilizer, and farmers will use cheaper seeds,” Gorbachev says.

Despite Ukraine’s large grain stocks, it is getting harder to feed its own people. Nika Teplits works hard at her bakery in the center of Odessa.

Looking at the products on display, it’s hard to think that there is a war outside.

But Nika’s bakery is running out of pre-war stocks, and she’s worried a wheat shortage will keep her from continuing her work.

“Part of the country is unreachable. The product cannot be transported. So there is already a shortage of supply,” he says.

On the farm, Boris says he will continue to fight the evil that is trying to destroy his business and country:

“People around the world will feel the results. For a long time, even after the war, because the world has changed.”

While Ukrainian farmers will feel the pressure, world leaders will face the pressure to end this war and help families put food on their table.