Following the Free cyberattack, the IBANs of millions of the operator’s subscribers fell into criminal hands. And these documents can be used to make fraudulent withdrawals from their bank accounts.

The gigantic theft of personal data suffered by the operator Free has been in the news for more than a week. And for good reason: more than 5 million IBANs, an ultra-sensitive banking document, were stolen and, above all, sold at auction on a marketplace linked to cybercrime. If Free tries to minimize the matter, by claiming that the IBAN alone does not allow malicious actors to drain the bank accounts of the people concerned, the reality is unfortunately much more worrying.

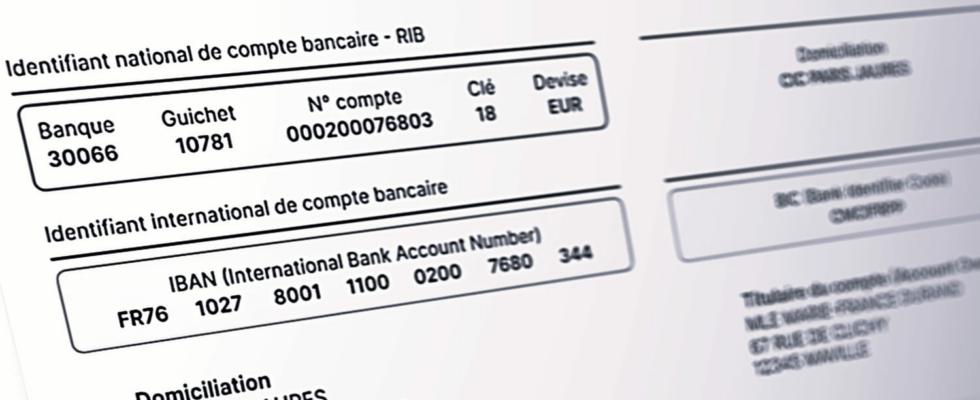

Because the IBAN, for International Bank Account Number is a number that identifies a bank account and the main information needed to set up a direct debit. This payment method is particularly practical for paying recurring expenses, such as subscriptions to online services, the supply of electricity or a car loan. Unfortunately, it is not infallible and can be subject to fraud, as the resounding SFAM affair has recently proven.

Indeed, it is very easy for a malicious company, and even more so for criminal actors, to set up an abusive or fraudulent direct debit. To withdraw money from an account, a creditor must normally submit a SEPA direct debit mandate (Single Euro Payments Area) signed by the debtor at the latter’s bank. However, at the time of presentation, the banking establishment does not always, if not almost never, check the signature of the mandate, whether handwritten or electronic.

Thus, a company or a criminal with a person’s IBAN can very easily generate false SEPA direct debit mandates, and send them to a bank to unduly drain a bank account. And as long as the law does not require strong authentication or a so-called “advanced” electronic signature before setting up any direct debit, this method will continue to work.

However, it is possible to protect yourself against abusive withdrawals by being vigilant, and even obtaining a refund of the amounts debited. First, you can consult the list of active direct debit mandates on your bank’s online space or application. By consulting it regularly, for example once a week, you will be able to identify suspicious samples, past or future.

If you spot an unknown or abusive direct debit, you can certainly temporarily suspend it from your bank’s online space. To revoke it definitively, you will need to send a letter, preferably by registered mail, to the creditor at the origin of the direct debit and to your bank, indicating the Unique Mandate Reference. You will find this code, made up of letters and numbers, in the list of mandates mentioned above.

Then, even if your account has been debited, you can request a refund from your bank. If this is a direct debit that you previously authorized, you can dispute it up to 8 weeks after the debit, and your bank must reimburse you within 10 working days of your request. In the case of a fraudulent direct debit, for which you have not signed a contract or mandate, you can contest it up to 13 months after the debit, and your bank is required to reimburse you one working day after receipt. of your dispute. In both cases, it is preferable to send your complaint by registered mail to your account holder.

Keep one thing in mind: the revocation of the direct debit mandate does not cancel the origin of the debt, which will therefore remain due if it is legitimate. A company or a malicious actor could therefore claim that you have signed a direct debit mandate for their benefit, for example by telephone. So prepare your defense well, and demand in writing that the company in question provide you with proof of your consent to the collection, not forgetting to report the company to the competent consumer protection authority.