On the sidelines of the Gaia mission, American researchers found, by studying the dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way, that the majority of these galaxies had only recently arrived in the area. This discovery has implications for our understanding of the interactions between normal galaxies and dwarf galaxies, and raises questions about the “life expectancy” of a dwarf galaxy on the edge of a more massive galaxy.

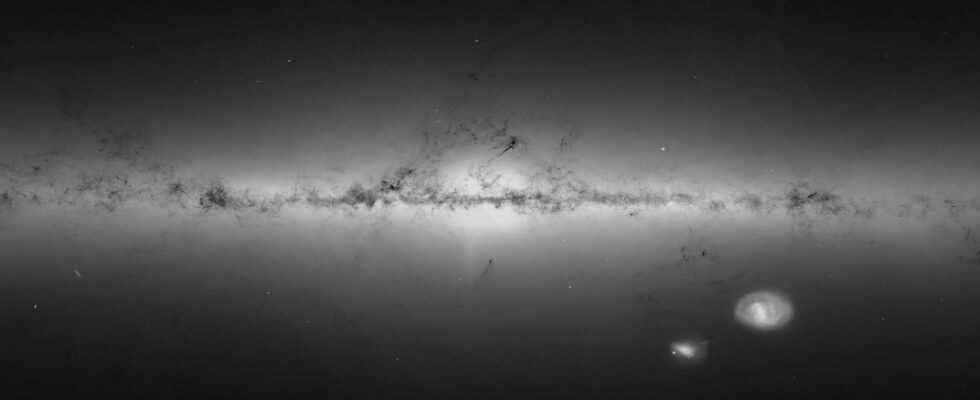

Scientists who participated in the study relied on data collected by the satellite Gaia, from the European Space Agency (ESA), designed to observe and measure the characteristics of more than a billion celestial objects in order, among other things, to improve our knowledge of the structure and evolution of our galaxy, the Milky Way. Bringing together the joint work of 20 countries, the mission enabled the most detailed three-dimensional mapping of our galaxy to date.

Gaia, a satellite to explore our galaxy

We now know that the space surrounding our Galaxy is not empty, but is teeming with dwarf galaxies, of only a few thousand stars, thus forming a local subgroup. Today there are about fifty dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way, although they are not all necessarily gravitationally related to the latter. The largest galaxy with a confirmed orbit around the Milky Way is the dwarf galaxy of Sagittarius.

Neighboring galaxies recently arrived on the outskirts of the Milky Way

By studying the data collected by the Gaia satellite, the scientists found that a large part of these galaxies exhibited excessive angular moments: in other words, most of the dwarf galaxies observed around the Milky Way move much faster than other objects known to orbit our galaxy.

These dwarf galaxies would not have been close enough to the Milky Way for long enough to be in gravitational interaction with it, leading scientists to believe that they only recently arrived in the area, less than two billion years ago. (the age of the Milky Way is estimated at 13.5 billion years).

What would have happened to the first satellite galaxies?

We now know that during its history, the Milky Way has repeatedly swallowed other galaxies: for example, the galaxy Gaia-Enceladus would have been incorporated into the Milky Way some 10 billion years ago, as evidenced by a population of stars orbiting at energies relatively weak. The dwarf galaxy of Sagittarius is currently disturbed by gravitational forces of ours, and is gradually integrated into it, and this for about 4 billion years.

In view of all these observations, according to François Hammer, of the Paris Observatory, “ the simply gigantic gravitational force of the Milky Way would easily destroy a dwarf galaxy after one or two passes around it “. Dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way would then have only one life expectancy limited.

The dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way would then have only a limited life expectancy

But the scientists of the study go further: if the gravitational force of the Milky Way is too great to allow a dwarf galaxy to subsist on its face for more than two passes, how could a dwarf galaxy survive any longer ( as we had thought for the dwarf galaxies of the Milky Way)?

To explain this, scientists would bring in the black matter, which would act according to them like a glue consolidating the dwarf galaxies. The possibility that these galaxies harbor a certain amount of black matter is also widely considered, due to the movement of their stars which could only be explained by “normal” matter.

The history of our Milky Way now seems much more complex than previously thought, and this research would also suggest an important role of dark matter in the evolution of our galaxy.

—

Futura in the Stars, it is the unmissable meeting place for lovers of astronomy and space. Every 1st of the month, meet us for a complete tour of the ephemeris of the month, with advice on how to best observe what is happening in the sky. A special episode published every 15th of the month will offer you to learn more about a particular object or event that will mark astronomical and space news.

—

Interested in what you just read?

.

fs3