The brain is the least known organ in the human body. Yet it is the one that fascinates the most. How does it work? Can revealing its mysteries help us understand ourselves better? While research is progressing, cognitive sciences are still in their infancy. “They don’t even have a stabilized theoretical framework yet. We’re talking about preparadigmatic sciences,” explains Albert Moukheiber, doctor of neuroscience and clinical psychologist, in his latest book Neuromania (Allary éditions), published on September 5. In other words, there are still many uncertainties. Which allows for a multiplication of possible interpretations of the results of scientific experiments and facilitates the projection of all sorts of beliefs, even if it means using neuroscience in every way – and not always wisely.

Coaches, authors and other personal development speakers invoke this discipline at every turn, promising to “unlock your potential” or “discover your hidden self”. Promises that are often false, warns Albert Moukheiber, which spare neither companies that use and abuse scientifically unfounded “cognitive tests”, nor the media that oversimplify or distort this discipline. Neuromania also becomes a plea to change our view of pain, mental illnesses and even certain prohibited substances, such as psychoactive drugs. This book invites, above all, to better understand these fascinating sciences.

L’Express: Why did you want to write this book: the manipulation of neuroscience, scams, the general public’s poor understanding of your discipline?

Albert Moukheiber: For all of these reasons. And because misinformation on this subject pigeonholes people, which can have harmful consequences. If a person wants to become an engineer and takes a “cognitive test” to determine whether they use their left brain, supposedly the one for logical and rational reasoning, or their right brain, intuitive and emotional, and the result indicates that they should move towards a career as an artist, this can have an impact, while this division is rejected by most current researchers.

Others still believe that their true self is hidden in their brain and that discovering it would explain how they work. Some are willing to spend a lot of time and money in this quest, even though our identity does not work that way. It is important to explain why these concepts are false and why they abound.

You particularly denounce personal development coaches and other “experts” who invoke neuroscience to sell their solutions. How is this problematic?

As a psychologist, I see many patients who want to know who they are. Introspection is useful, of course, but if it is aimed at arriving at a “eureka” moment where one would discover THE answer, as if it were possible to discover the “me” area of the brain, it can be frustrating.

Because research suggests that our brains transform separate identities into a unified identity called “self.” While we may have some consistency in some facets of our personalities, there is no evidence that there is a true self hidden beneath the many facets of our being. So when you set out to find your true self, its hidden desires and aspirations, you are on a path that has no end or purpose, because it evolves as you go.

It is much more interesting, rich and stimulating to know that the answer is complex than to say to yourself: “There is a treasure in me and I can’t find it”, or to go from coaching sessions to various therapies, from personality tests to career paths, from yoga workshops to professional reinventions without ever managing to lift this mystery, since there is none.

In your book, you also criticize the media. According to you, their poor treatment of neuroscience contributes to confusion about our knowledge of the brain. Why?

I take as an example an article press release entitled: “Here’s what happens in your brain after a heartbreak”. It is based on a study by a neuroscientist conducted using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures the activity of different areas of the brain, in 15 people who have been through a breakup. The article presents the study by making us believe that we have understood love thanks to brain imaging. Neuroscience is much more interesting than this type of reductionist, sad and impoverishing story, as well as being false. This takes us away from real explanations. It’s a bit like trying to understand a car by looking only at the carbon atoms that make it up.

We are in the early stages of understanding the brain. We have made a lot of progress in recent years, but we were starting from scratch. The development of FMRI dates back to the 1990s. For now, scientific studies are simply descriptive. That’s already good. But today, some people are selling dreams by passing off these descriptive models as explanations.

You also warn about the use of personal development tinged with neuroscience in the business world. What do you fear?

This form of personal development obeys the principle of individualization of collective problems under the cover of high-sounding formulas borrowing from the vocabulary of neuroscience or psychology.. This can lead to situations where, instead to talk about salary or working conditions, we suggest doing yoga exercises to relax, to unwind. The instrumentalization of neuroscience to push towards individualism, towards a kind of unbridled neoliberalism where the problem would always be “in you”, bothers me. My discipline is too often used to put forward political ideologies.

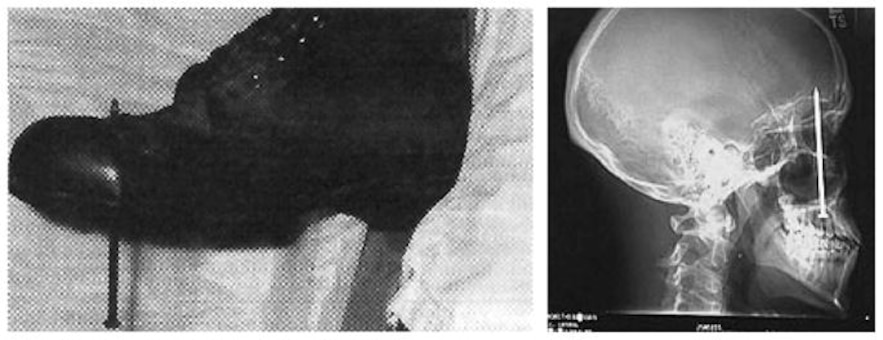

You illustrate in particular the mysteries that remain to be discovered with work on pain. Two astonishing clinical cases present a worker who drove a nail into his shoe and screamed in pain, convinced that he had pierced his foot when the nail went between his toes, and another where the patient had a nail several centimeters long in his skull but did not realize it and did not suffer from it. How is this possible?

What I’m trying to explain in this part is that pain is a sense and an emotion at the same time. For a long time, the general belief was that our senses were bottom-up, that is, they perceived the outside world and sent the information back to the brain. In reality, it goes both ways, so also top-down. For example, the brain sets up predictive processes and has room to maneuver over our perception. There are predictive processes of pain, and when there is an anticipation effect, we can feel non-existent pain or, on the contrary, not feel it.

© / BMJ Publishing Group Ltd/Associated Press/Wide World Photo

You indicate that similar processes explain the placebo and nocebo effects, that is, the feeling of positive or negative symptoms after taking a treatment, when it is, for example, only salt water. How does this work?

This is the expectation effect of our brain, which will modulate our body according to an expected effect. For example, we can give an “empty” pill, devoid of therapeutic action, but depending on its form or the speech that accompanies its taking, patients can feel positive or negative effects. Sometimes, this effect can work even if the caregiver specifies that it is a placebo.

In Neuromania, I illustrate the nocebo effect using A study on vaccines during the Covid crisisin which participants experienced adverse effects, such as headaches and fever, classic side effects of the vaccine, even though they had received a placebo! We don’t really understand how this works yet. There are possible explanations, but the model remains to be discovered. I find it fascinating and fabulous.

You also believe that pain is still poorly managed in France, with medication being prescribed too automatically due to lack of time. This is also a recurring criticism from supporters of “alternative therapies”, who accuse modern medicine of being too cold and too fast. Don’t they derive part of their popularity from this accusation?

Yes, there is a lack of support in general. But doctors are also victims of the system, because they too would like to have more time for their patients. Take antidepressants. They can of course be useful and effective, but their prescription is sometimes automatic because psychiatrists do not have the time to explore other treatments that could be just as beneficial, but more time-consuming. And yes, we often blame people who consult naturopaths, osteopaths, homeopaths, etc. They may be selling hot air, but they also sell attention. And attention can work.

There are also reasons to be happy, especially thanks to the revolution brought about by functional magnetic resonance imaging. However, you point out that this tool is not powerful enough to explain everything. What technology would we need to better understand our brain?

Today, looking at the brain with MRI is a bit like photographing the Earth from the Moon and trying to understand the architecture of Paris and the movements of its inhabitants… We need better resolution. What would help us even more would be to have portable MRIs, a technology that is not yet on the agenda. Because we know that the functioning of the brain is dependent on the context in which we find ourselves. But MRIs are all performed in hospitals, with the patient lying down. The brain is therefore not in its natural environment.

There are also methodological problems, such as This is shown by a study published in 2017. by two neuroscientists who were trying to understand how a microprocessor works using the tools of neuroscientific research. The processor studied was, of course, much simpler than a brain. However, the researchers’ conclusion is clear: the large amount of data obtained about this chip did not allow them to make significant progress in understanding how it works. In short, we have a problem with the method of investigation. Researchers are working on it, but in the meantime, we cannot promise miracles.

You introduce quotes in every chapter. But in the third one, it’s just a smiley: ¯_(ツ)_/¯. What does it mean?

This is a redundant joke I play on myself. I actually have this smiley face tattooed on me. It’s a well-known Internet character: the “shrug.” It represents a kind of life philosophy saying, “OK, we don’t know, we’ll see.” In this chapter, it’s a way of saying, “We’re very far from solving all the problems, but we’re doing what we can.” It’s not so bad not to know everything, it’s actually quite stimulating, because it means there’s still a lot to discover.

I feel like a lot of people think that science has already answered everything. That’s not true, there’s still a whole continent to discover. It may seem pretentious, but I would like the young people who read me to be able to say to themselves: “There are lots of unknowns, I want to get started!”

.