Published on

updated on

Reading 3 min.

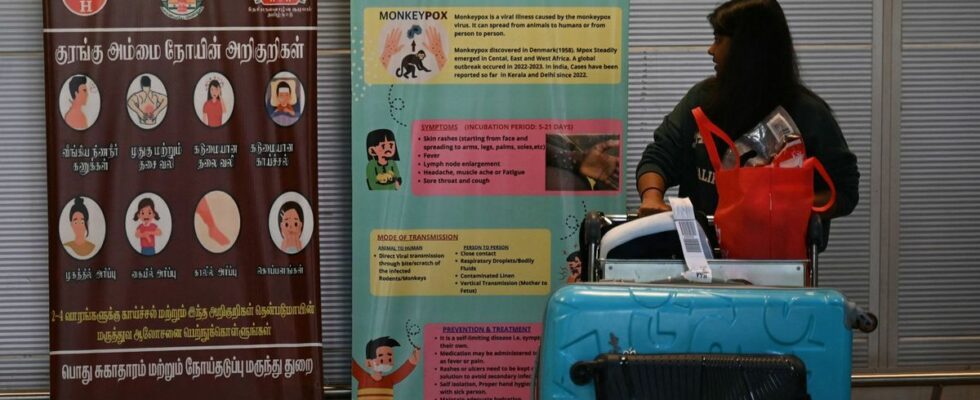

How dangerous is MPOX? Is one strain more deadly than another? As the world worries about the spread of the disease, the answers are less clear-cut than some alarming figures taken out of context would suggest.

MPOX, which has been declared an international emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) since mid-July, appeared in humans around 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Mortality depends on the quality of care received

For decades, the disease, long called “monkey pox”, remained confined to around ten African countries and was attributed a very vague mortality rate of between 1% and 10%.

This uncertainty was further accentuated in 2022 when the disease spread to the rest of the world. In the new countries, particularly Western ones, where MPOX circulated, mortality was very low: around 0.2%.

These fluctuations have several explanations. First, the health context is different between African countries where the disease has been present for a long time and Western countries where it has recently appeared.

“The danger to individuals depends strongly (…) on the quality of standard care in the region of residence“, virologist Antoine Gessain, a specialist in the disease, emphasizes to AFP.

In other words, a patient will have a much better chance of receiving quick and good treatment in Europe or the United States than in the majority of African countries.

It is therefore very likely that the 3.6% mortality rate currently recorded in the DRC, which is hit by the main ongoing epidemic, would be much lower if the virus were to start circulating actively in Western countries.

Malnourished children among main victims

The context of the epidemic also affects contagiousness: some patients are much more vulnerable than others.

Thus, the deaths recorded in the DRC – more than 500 out of just over 15,000 recorded cases – are mainly children, in a country where malnutrition is significant.

By contrast, the much rarer deaths in the 2022-23 outbreak – some 200 out of about 100,000 cases – were among adults with immune systems compromised by HIV infection.

These different profiles can be explained not only by geography but also by modes of transmission that vary according to the epidemics. The 2022-2023 epidemic mainly spread during sexual relations between homosexual or bisexual men.

Finally, one factor adds a layer of complexity. MPOX is caused by different families of viruses, called clades, and it is difficult to determine their intrinsic differences in terms of danger and transmission.

Complicated comparisons

The 2022-2023 outbreak was caused by clade 2, which is mainly active in West Africa but also in South Africa. The deadly outbreak in the DRC is caused by clade 1, which is concentrated in Central Africa.

But that’s not all: another epidemic is underway in the DRC, affecting mainly adults, and it is linked to a recently emerged derivative of clade 1, variant 1b.

This situation contributed to some media confusion in which the 1b variant was described as more dangerous than all pre-existing versions.

“We read in the mainstream media some pretty affirmative things about the seriousness or severity of the new 1b sublineage, while there is not much to support them.“regrets Dutch virologist Marion Koopmans to the British Science Media Centre.

“What is known is that clade 1 is associated with more severe diseases than clade 2.” she emphasizes.

Indeed, clade 1 outbreaks have historically been associated with higher mortality than clade 2 outbreaks. But even on this score, some researchers urge caution before asserting that clade 1 is inherently more dangerous.

The question is all the more crucial since this version of the virus was first detected outside Africa, in Sweden, in mid-July.

But, between the different clades, “The comparison is very complicated, given the importance of the context and the type of population at risk: how can we compare malnourished children and HIV-positive adults?“, insists Mr. Gessain.