Jean Slawinski, scientist and researcher at the Sport, Expertise and Performance laboratory of Insep, explains to RFI how science is improving athletes’ performances today. Example with the sprint studied through the Fulgur project is part of the perspective of the Olympic and Paralympic Games of Paris 2024.

RFI: First, explain to us what the Fulgur project is?

The Fulgur project was born from important questions around injury, particularly hamstring injuries. This is a very common injury among sprinters and very disabling since they can no longer train and therefore progress. Nor participate in competitions. We see this clearly when we have athletes who get injured just before the Games, they cannot train to compete. So, it is a project that is led by the Sport, expertise and performance laboratory, by Gaël Guilhem, our lab director, and which brings together a consortium of 30 researchers from partner institutes and university laboratories to try to better understand the occurrence of this injury.

Is it also a way to improve sprint performance by better understanding the origins of the injury?

Of course! If we reduce the occurrence of injuries, sprinters can train more and better. And for longer. In fact, performance will necessarily improve. Because if, for example, we start training in September, and then in January, there is a hamstring injury, that means we are off for between one and two months. As a result, we lose all the benefit of the preparation.

What causes this hamstring injury to recur in sprinters?

From what we know, it is the stress at speed levels and in specific angles for sprinting that will promote the occurrence of the injury. So mechanically, when we have over-stress of the hamstrings at very high knee opening speeds, at specific angles, we stretch the muscle too much, and at that point, there is a risk of injury. After that, there are many influencing factors, there is the whole environment, diet, sleep level, the sprinter’s own qualities. Are there specific qualities or specific muscle structures that make some athletes more susceptible to injury than others? The idea of the Fulgur project is to look at all these aspects and cross-reference them: the level of training load, the athlete’s environment and a more local approach to the properties of muscle tissue.

In terms of results from this project, are you more in demand from coaches, from athletes?

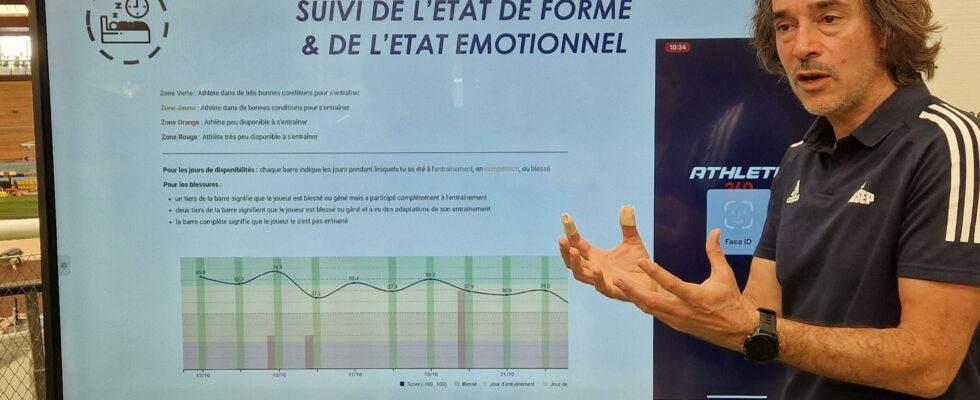

Yes, we sense a craze. Collaboration between the world of sport and research has a long history. It has not always been easy. This type of project, in my opinion, has the advantage of being able to unite the stakeholders, force them to talk to each other, to work together on these issues and therefore to ensure that people understand each other a little better. The project has contributed in terms of implementing tools. For example, on GPS, we have more and more coaches who are interested in monitoring, quantifying load, analyzing competition, analyzing performance or evaluating their athletes. We have made some of the coaches aware of the need to objectify the parameters of training and performance, and I think that is a positive point, a big positive point for this type of project.

The best sprinters come mainly from Jamaica or the United States. How does French science, used in the service of sprinting, compare to these countries?

I don’t have any figures, but I’ll just give you some impressions or feelings. I don’t think we’re behind, far from it, compared to other countries. When you see the skills we make available, those of coaches, researchers, young doctoral students, all the colleagues who work on athletes’ performance projects, we’re as good as the others, if not better. After that, performance is multifactorial. It would be lying to you to say: “it’s because we’re going to have this technological and research approach that we’re going to win medals”. It’s still more complex than that. And fortunately so. We’re here to come and objectify training data, shed light on performance and give coaches tools to decide. They’re the ones who have the knowledge, who know their athletes. And we, in the process, try to provide them with precise figures to help them in their decisions. We strongly believe that this is the approach that allows us to be more precise and therefore to win. The search for excellence, the search for high performance, is precision, we must be precise in our figures, we must not make mistakes in our charges. Being extremely precise is what will make us win.

If we compare ourselves to China or the United States, we have a good pool of talent in detection, but not as big as in these two countries. We don’t have the same ways of training, so we need this objective approach and hope that each athlete, thanks to this scientific approach, achieves their best, their best performance. And if their best is the Olympic title, I remain convinced that we will have contributed a little to that.

If we were to draw the profile of the perfect sprinter, what place would science occupy in this profile alongside the coach and other factors?

Good question, but very complicated to answer. It depends on the coach, the environment, the athlete. We take our reference which is Usain Bolt, did he have all this technology to perform? I am not going to preach for my parish, but maybe if he had had it, he would have done much less than 9’58 (the world record for the 100m). We do not know that. The athlete, the coach must want to work like that. Have this curiosity to know in order to then inform his practice, his choices. “I planned this, it had such a result. The researchers or science told me that we were in this direction, we progressed in such a part. From there, I will be able to adapt my training and progress well after one, two, three years of experience”.

There is no magic in fact, we cannot design the perfect sprinter. Yes, science plays a large part in performance. I am a scientist, so I want to tell you that it is central today. We treat diseases thanks to science. So, yes, science will help us improve performance.