It was seventeen years ago. “I am an angry woman,” thundered Ségolène Royal, the socialist presidential candidate. In 2007, the words left her opponent, Nicolas Sarkozy, speechless for a moment. In the hushed debate between the two rounds, the expression of emotion, generally absent from political communication at the time, seemed almost strange, disconcerting. Three presidential elections later, Ségolène Royal’s outburst seems quite trivial. The emergence of the red caps, the explosion of the yellow vests, the grumbling of farmers, the explosion of the #MeToo movement and political outbursts… Now, this emotion is everywhere, all the time, omnipresent on screens, flourishing on the corners of our streets.

In a study entitled “France under our tweets”, Yann Algan, professor of economics at HEC, and Thomas Renault, lecturer at the University of Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, examine the passions that run through us. From 2011 to 2024, the two researchers sifted through the messages written by 160,000 accounts on the social network X (formerly Twitter). Their goal: to determine the main concerns of the French (in economic, societal or political matters) and examine the emotions linked to them.

Anger and revolt

Over the last decade, messages expressing anger increased by around 66%, before it exploded in full force at the time of the yellow vests. Since this surge, it has only slightly decreased, increasing again in 2022, and being accompanied by an increase in messages linked to revolt (6 to 12%). Of all the concerns of the French, 35% of messages reflect this feeling, seconded by worry or fear (14%) and revolt (12%). Positive emotions are the big losers of the period. Confidence, happiness, enthusiasm or even hope do not even represent 10% of the tweets sent by the French.

To reach this conclusion, the authors built an original database of 784,300 messages, sent by users of geolocated X accounts. To determine each person’s political affiliation, the study uses 40 keywords that come up most often in the political platforms of the three blocs of these elections (New Popular Front, Ensemble-Renaissance, National Rally), and observes the political figures followed by each user. Aided by artificial intelligence, “we analyzed between 5,000 and 10,000 messages from each user, taking great care to remove any robots,” explains Yann Algan. According to him, the X platform has become a “privileged place” to “take the pulse of the emotional voter.” “By going through X, we were able to measure the feelings of French society on a multitude of subjects – transport, education, school… Traditional surveys cannot have the same richness, continues the economist. Our study is much closer to the electoral results.”

© / Legend Maps

A different anger

Anger represents nearly a third of conversations (around 30%) among voters of traditional parties (left, center, right), increasing among people close to the radical left (34%). It explodes among individuals associated with the extreme right, where feelings related to anger represent nearly one in two conversations. Unlike center voters – the only ones to be less affected by anger – those inclined to the extremes have a “much lower” level of satisfaction in life, which leads them to negative feelings. “In particular resentment,” points out Yann Algan. These two groups believe that the government and institutions have not been able to protect them against the excesses of capitalism, which explains why their messages often evoke unemployment or questions of purchasing power.”

Over the past fifteen years, two themes have concentrated French fury: first, issues related to taxation and taxes (60%), then, those related to immigration (55%). However, a slight change has taken place since 2018: it is now issues related to delinquency (60%) that particularly arouse anger, then the subject of taxes (59%) and immigration (58%). “When we talk about resentment among the French, we are not talking about the same anger, warns Yann Algan. Where voters of the radical left will talk to you about the minimum wage, reducing inequalities, those of the RN will cite taxes or duties.”

A “France that suffers”

French people who subscribe to the accounts of the leaders of the far-right party are thus much more likely to complain about taxes but also about delinquency (70%), housing problems (43% against 32%), or even Europe (48% against 32%). Concerns, observe Yann Algan and Thomas Renault, “very close to the yellow vest movement”, which the RN has seized upon, particularly on the issue of purchasing power. “Marine Le Pen has been able to quickly, in recent years, move away from her initial positioning as a protest party to try to embody the ‘France that suffers'”, observes Mathias Bernard, university professor of contemporary history and specialist in the political history of France.

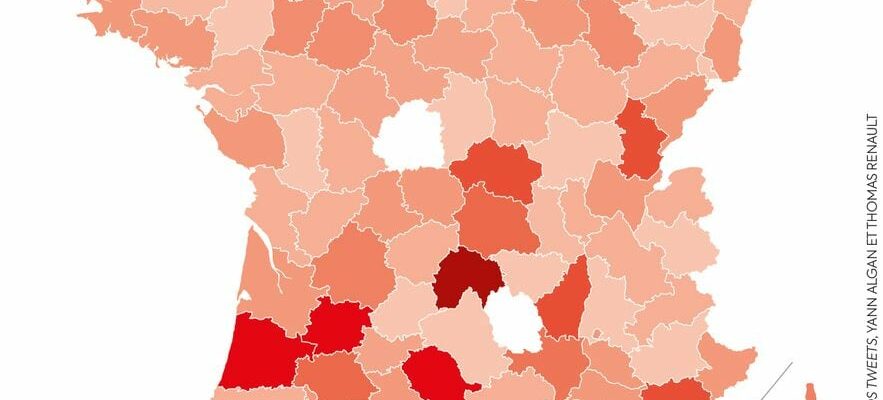

The study draws a “geography of anger” that is found in the ballot boxes. From 2018, it exploded in the South-East (Alpes-Maritimes, Var), and in Hauts-de-France (Pas-de-Calais, Aisne), traditional bastions of the far-right party. But it is also progressing in Brittany, a traditionally left-wing land, in which the breakthrough of the National Rally was one of the surprises of the European elections. In Auvergne (Haute-Loire, Cantal), or in the South-West (Landes), the share of discontent in conversations (between 35% and 45%) is close to the same orders of magnitude as the party’s score in these elections. “Many areas where the RN vote is increasing correspond to the industrial tertiary sector. Jobs as nursing assistants, truck drivers, jobs in logistics, where the individual is often isolated, prey to solitude… Which leads to distrust of others.”

Emotions, the driving force behind political choice

Taking these emotions into account and their distribution in the three dominant blocs in the legislative elections (NFP, Ensemble and RN) is therefore crucial to understanding the polarization of voters. By referring to an Anglo-Saxon model of political psychology, Affective intelligencethe researchers attributed several characteristics to each of them. On the one hand, worry or fear, which leads to an increase in the perception of risk. Emotion, which was the majority during the Covid epidemic, had pushed the French to scrupulously respect the rules of confinement. The latter pushes one to be more conservative – and therefore to prefer the status quo – and is found above all in the messages of Ensemble supporters. Anger, on the other hand, encourages one to overthrow the established order and opt for more radical candidates. This is the logic of “nothing left to lose”, of a clean slate. “The two blocs of the radical left and the RN manage to emotionally capture their electorate, notes Stewart Chau, director of studies at Verian and author of The Opinion of Emotions (Fondation Jean-Jaurès/Ed. de l’Aube). They use a rhetoric of rupture where the presidential party is in continuity.” Algan and Renault describe atomized French people, much more driven by individual logic than by ideologies. Class struggles – although still present on the left – have been replaced by “communities of emotions”. “When we ask the French what motivates their political choices, they talk about their daily lives, and then their emotions. It is a key factor in their orientations”, continues Stewart Chau.

These latter become the driving force behind political engagement, but also a way of understanding the world. In people dominated by anger, recent studies show that it prevents the brain “from registering new information that contradicts their beliefs”. When the anxious voter seeks at all costs elements to calm their fears, the one drowned by fury can no longer inform themselves – or, in any case, can no longer integrate data that goes against their certainties. “Angry people no longer hear the slightest contradictory information”, continues Yann Algan. Climate skepticism or the anti-vaccine movement are examples of this. “Be careful, however, not to use emotions as the only explanations for voting. The ideological dimension remains very important: the Macron vote remains in part a liberal vote or the RN vote a nationalist vote”, qualifies Mathias Bernard. Taking them into account nevertheless allows us to shed more light on current electoral dynamics. “It is now crucial to take emotions into account in politics. They are no longer just subjective affects, but a total social fact,” concludes Yann Algan.

.