On Friday, June 14, the Sciences Po alumni garden party ended in bloodshed. In fact, red paint was thrown at the entrance to the ultramodern premises on Place Saint-Thomas d’Aquin, in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, where some guests were greeted with shouts of “fascists” by a small group of activists claiming to be from the institution’s Palestine committee. In the gardens, a dozen students, armed with 40-euro entrance tickets and wearing surgical masks to hide their faces, burst in with banners and flags around 7:30 p.m.

“You drink champagne while children die in Gaza,” an indignant young man shouts from the balcony, where the administration has agreed to give him the microphone for five minutes. Leaflets incriminating Coca-Cola, one of the partners of the annual evening, guilty of maintaining commercial ties in Israel, are distributed. After an hour, the “performance” ends, in a stormy atmosphere, after Pascal Perrineau, the president of the alumni association, turns up the music to cover the noise of the demonstrators.

“We will remember you,” one of the students told the political scientist, according to her own words. “Dozens of former students then came to me, saying: “We didn’t think it was this serious!” And some told me that they used to give 1,000 or 2,000 euros but that this time it was over,” says Pascal Perrineau. The final curiosity of this eventful evening was that the protesters ended the evening… by helping themselves to the buffet, while a few guests tried to start a dialogue. “Some then enjoyed the cocktail and the petits fours. After criticizing us for drinking champagne… It was quite surprising,” says Perrineau.

Threats to funding

Since March 12, fever has gripped Sciences Po. That day, 300 students occupied the emblematic Boutmy amphitheater, where Raymond Aron and Dominique Strauss-Kahn were giving classes, at the call of transnational pro-Palestinian committees. Was a Jewish student prevented from entering the room? After an internal investigation, eight students have now been referred to the disciplinary board, in parallel with a criminal investigation.

Faced with the unrest, the management seems to have procrastinated, even trying to dissuade Samuel Lejoyeux, the president of the Union of Jewish Students of France (UEJF), from going to the site. “A famous expression says that the fish always rots from the head. I think that’s what the French are telling themselves,” Gabriel Attal snapped the next day, after inviting himself before the administrators of the National Foundation of Political Sciences (FNSP), the school’s supervisory body. “The French expect that when public money is committed to financing institutions, there is a 200% guarantee that republican principles are respected everywhere and at all times in these institutions. And so, there will now be an immediate link that will be made between the two,” he chiselled.

The indictment takes on the tones of a threat: if the Grande École does not react firmly, its funding could be cut. However, Sciences Po’s budget equation is based on an extremely fragile balance. In 2019, the latest figures published, annual state subsidies amounted to 69 million euros, for a budget of 200 million euros. The other two thirds are broken down between contributions from patrons and tuition fees, increased in 2022 and then in 2023, to reach 6,740 euros on average for a master’s degree. If the state withdraws, students’ families will have to make up the difference.

Vacation in the storm

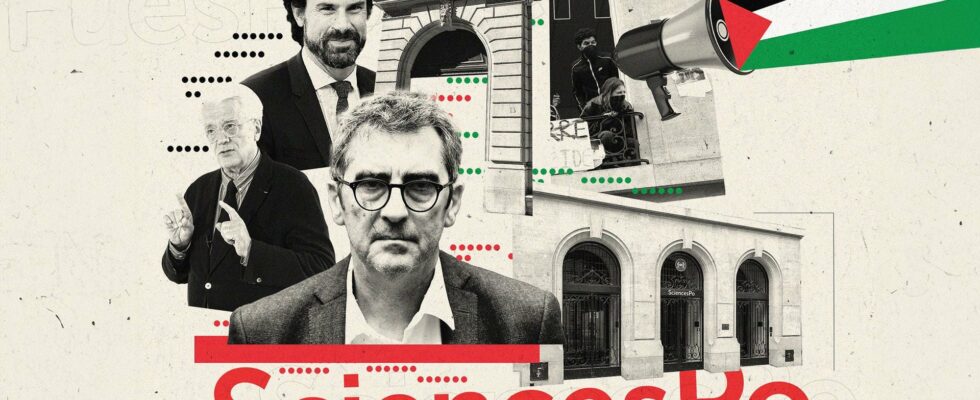

That same March 13, Sciences Po was decapitated. Mathias Vicherat, the director elected after the Duhamel affair in 2021, learned of his referral to the criminal court for mutual domestic violence with his ex-partner. He resigned immediately, also exhausted by a virulent campaign against him. For weeks, a handful of students put up “Vicherat resign” posters in the “barge”, as the large entrance hall leading to the lecture halls and the management offices is called.

Forty days earlier, the number 2, the Russian economist Sergei Guriev, announced his departure for the London Business School. The power vacuum opens in the middle of a storm. The new director must be appointed on September 20, unless the Minister of Higher Education objects, a hypothesis that is anything but textbook if the government is led by Jordan Bardella. “What is dramatic in all this is that it is 200 far-left activists, wokeists, who are preventing 13 or 15,000 other students from following their courses,” complained Sébastien Chenu, RN vice-president of the National Assembly, on April 30.

In the meantime, Jean Bassères must lead. At 64, the financial inspector, appointed provisional administrator of Sciences Po for five months, has no personal ambitions. Pragmatic and friendly, he wants to leave a peaceful establishment. His plan? To remain discreet – he has theorized not to introduce himself officially to all the students – and to clean up the atmosphere. On April 18, he goes to Sciences Po Menton, a campus specializing in the study of the Arab world, to show his support for Jewish students who are sometimes ostracized or automatically assimilated to the Israeli government. “The students knew the Palestinian narrative like the back of their hand, but not at all the Israeli point of view,” noted Denis Charbit, an Israeli professor of political science, who came to give classes for a semester. “They are young, they are romantic,” Bassères repeats to his interlocutors, touched by the raw sensitivity of the activists he receives in his office.

Posters by Marie Toussaint

In his approach, the senior official overlooked one point: the Sciences Po activists are nothing like the sometimes virulent but reliable unionists with whom he negotiated when he was head of Pôle emploi, between 2011 and 2023. The announcement of disciplinary procedures after March 12 triggered their fury. They blocked the staircase leading to the management offices. Then, on April 24, 150 students pitched their tents on the Saint-Thomas campus. Jean Bassères asked the CRS to evict them, a first in the history of the school. In the following days, around a hundred students continued the mobilization in and in front of the establishment, in the presence of executives from La France Insoumise, or Elias d’Imzalène, a preacher close to the Muslim Brotherhood, seen in the crowd. Tragi-comedy of student activism: on Friday, April 26, the banners on the windows denouncing the “genocide” in Gaza were lifted for a moment, and we realized that they had been made on the back of election posters for Marie Toussaint, the candidate for Europe Ecologie-Les Verts.

On May 2, a “town hall”, meaning a public debate, took place in the school on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Jean Bassères thought he had thus negotiated the end of the occupation of the premises. Alas, as soon as the discussions ended, during which Sciences Po ruled out giving up its partnerships with Israeli universities, the Palestine committee voted for new blockages. Classes were cancelled the next day. The exams, however, would take place, except on the Reims campus where three tests remained to be rescheduled at the end of June.

“Free Palestine”

In the meantime, Valérie Pécresse, the president of the Ile-de-France region, has threatened to suspend the million euros annually paid to the school. On June 19, American billionaire Frank McCourt also announced that he was suspending his annual funding of 2.5 million euros to Sciences Po, while waiting to find out who the new director is.

Because in recent months, the debate has turned into the Battle of Hernani within the teaching profession, making the next election a crucial issue. The Center for International Research (Ceri) and the Medialab of Sciences Po, specialized in sociology, have taken a position in favor of freedom of expression for students, against the evacuations. More discreetly, the History Center has been displaying a “Free Palestine” banner under its windows on Rue Saint-Guillaume for several weeks. Conversely, 500 former students, including teachers Pascal Perrineau, Gilles Kepel and François Heilbronn, published an opinion piece on the L’Express website on April 30 against “the instrumentalization of the school by a violent minority that undermines all the principles of Rue Saint-Guillaume.”

On June 5, the refusal of the Sciences Po scientific council to extend Pascal Perrineau’s emeritus status appeared as a new episode in this struggle for influence. The decision was purely honorary, but it was seen as a sanction against the political scientist, an uncompromising critic of radical activism on Rue Saint-Guillaume. “It is not up to a hysterical popular tribunal, nor to frustrated second-guessers, nor to a minority of activists to decide whether he can remain director,” he castigated after Mathias Vicherat was taken into custody in December.

In this context of tensions, the commitments of the various candidates are particularly scrutinized. After the refusal of Enrico Letta, former Italian Prime Minister, to run, Arancha Gonzalez, director of the School of International Affairs at Sciences Po, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain between January 2020 and July 2021, seems to be the favorite. A self-proclaimed “progressive”, this 55-year-old lawyer presents herself as a candidate for appeasement, with the support of many teachers. In private, she says she is not very shocked by the student unrest, as long as it remains peaceful.

Respected figures from the academic world are also candidates, such as Rostane Mehdi, director of Sciences Po Aix, who wants to “meet all the school’s patrons to reassure them” if he is elected, Pierre Mathiot, his counterpart at the IEP in Lille, or the former Secretary of State Juliette Méadel. Luis Vassy, current chief of staff of Stéphane Séjourné, Minister of Foreign Affairs, is another very serious competitor. The 44-year-old diplomat has identified a “triple crisis” at Sciences Po, “of image, project and governance”. This ENA graduate of Uruguayan-Argentine origin, naturalized French two years ago, proposes to reform the institution in depth and to “modernize the Descoings software”, named after the former director, who died in office in 2012, and who dreamed of making it a French Harvard.

His project includes the creation of a school of ecology, courses on conflict in international relations, courses without mobile phones, an introduction to research from the beginning of schooling, or an explanation of the French republican model. “We are not going to give up French secularism because journalists in Brooklyn ask for it,” he used to repeat to the Dutch when he was ambassador to the Netherlands, between 2019 and 2022. Two diplomats experienced in delicate negotiations tipped to lead the school: a sign that the situation is serious at Sciences Po.

.