Jan and Els, who live in the Netherlands, had been married for nearly 50 years. In June, the couple ended their lives together with lethal drugs administered by two doctors. This procedure, also known as bilateral euthanasia in the Netherlands, is rare but legal. Every year, more and more Dutch couples choose to die together

Some readers may find the statements in this news story disturbing.

Jan and Els, who decided to voluntarily take their last breaths together, parked their camper van in a sunny marina in Friesland, in the north of the Netherlands, three days before the procedure.

They had already spent most of their marriage on the move, in a caravan or boat.

Jan, 70, sat in the driver’s seat of the van with one leg tucked under his hip, the only position that could relieve his persistent back pain.

His 71-year-old wife, Els, has dementia and was now having difficulty forming sentences.

Wanting to show that he had no difficulty standing, Els pointed to his body and said, “Look, this is good,” and then pointed to his head and said, “This is scary.”

The couple met in kindergarten and became partners in each other’s lives throughout their lives.

Their shared passion for the sea, boats and sailing shaped the years they spent together.

Els gave birth to a son. While her son (whose name she did not want to give) was studying at a boarding school, she spent time with her parents on their houseboat during the holidays.

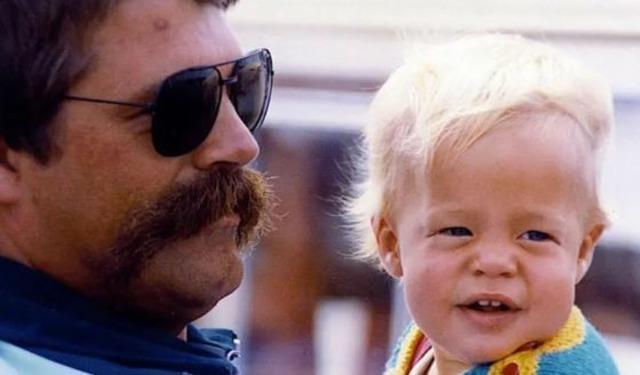

Photo of Jan and his son taken in 1982.

HEAVY PAIN KILLERS STARTED TO NOT WORK

Although the couple did some sea freight trading for a while, Jan, who had been lifting heavy loads for decades due to his job, began to experience serious back pain.

After a while, they moved ashore and started living in a caravan.

Jan had back surgery in 2003, but he could not recover. The heavy painkillers he took began to fail. But Els was busy teaching in the meantime.

From time to time they brought up the subject of euthanasia. Jan explained to his family that he did not want to live long with these physical limitations. It was around this time that the couple joined the NVVE, an organization in the Netherlands that advocates for the “right to die.”

“When you take too much medication, you live like a zombie. With my pain and Els’ illness, I thought we had to put an end to this,” Jan said.

What he wanted to end was his life.

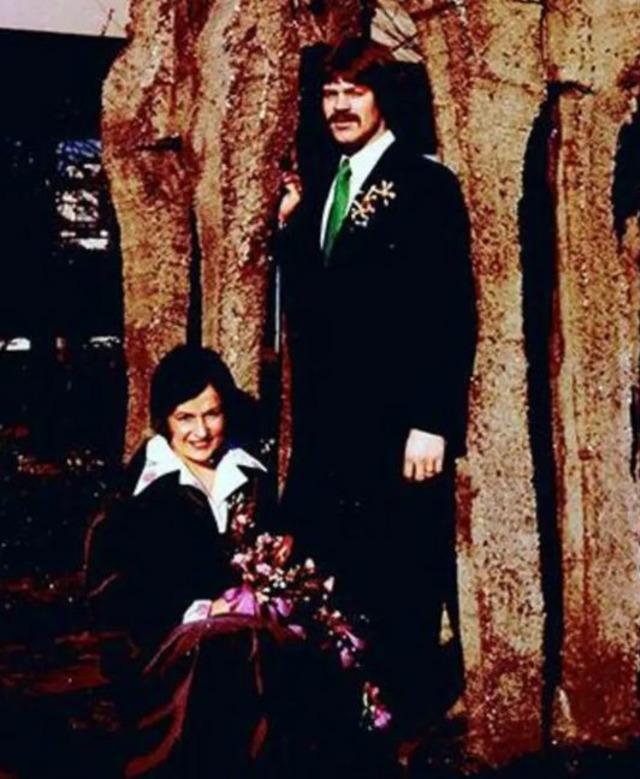

Els, whose photo was taken in 1968, was diagnosed with dementia in her later years.

TWO DOCTORS ARE TESTING HIM

When Els retired from teaching in 2018, she was showing signs of early dementia but was reluctant to go to the doctor, perhaps because she had witnessed her father die of Alzheimer’s.

When he was diagnosed with dementia in November 2022, he stormed out of his doctor’s office, slamming the door behind him and leaving his wife and son behind.

When Els learned that his illness was incurable, he and his wife Jan began discussing ending their lives together with their son, also known as bilateral euthanasia.

In the Netherlands, euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are legal if someone requests it voluntarily and is suffering physically or mentally, or if they have an illness that is “unbearable” and will not improve under medical supervision.

Every person who makes this request is tested by two doctors. The second doctor checks the evaluations of the first.

A total of 9,068 people ended their lives through euthanasia in the country in 2023. This is 5 percent of total deaths.

Most doctors do not even want to consider euthanasia for someone with dementia, says Dr Rosemarijn van Bruchem, a gerontologist and ethicist at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam.

These concerns are also reflected in euthanasia data.

In fact, of the thousands of people who ended their lives through euthanasia in 2023, 336 were patients with dementia.

According to Dr. van Bruchem, especially in the early years of dementia, patients may begin to consider ending their life because of the uncertainty of how the disease will progress.

Questions like, “Will I be unable to do the things I find important? Will I be unable to recognize my family?” come to mind.

When their family doctor did not want to be involved in the process, Jan and Els contacted the “Centre of Expertise on Euthanasia”, a mobile euthanasia clinic.

The institution, which accepts an average of one-third of the requests it receives, carried out 15 percent of assisted deaths in the Netherlands last year.

SHE HAS REJECTED ANOTHER COUPLE BEFORE

In such couple euthanasia, doctors must ensure that neither partner affects the other.

For example, Dr. Bert Keizer, who has performed euthanasia on two different couples so far, said he had previously denied the request of another couple.

When Dr. Keiser suspected that the patient had convinced his wife, he spoke to the woman alone; Dr. Keiser said, “The woman had many dreams for her future,” and understood that the woman did not want to die with her seriously ill husband.

The euthanasia process was stopped; the man died of natural causes, and his wife is still alive.

Dr. Theo Boer, a professor at the Protestant Theological University in the Netherlands who works on ethical debates in health and is known for his critical approach to euthanasia, thinks that improving palliative care will reduce the need for such practices.

Dr. Boer reminded that this news, especially when one of the country’s former prime ministers chose to die by euthanasia with his wife, made headlines around the world and said, “We have seen dozens of cases of couple euthanasia in the past year and in general there is a tendency to ‘heroize’ people dying together.”

“I HAVE LIVED MY LIFE”

Jan and Els could perhaps live in their caravan for years.

Did they think they would die so early?

Els replied, “No, I don’t think so.” Her husband said, “I’ve lived my life. I don’t want any more pain. We’re too old for the lifestyle we’ve been living. I think this needs to stop.”

There was another issue.

His doctors stressed that Els still had the capacity to decide whether he wanted to die, but that this would change as his dementia progressed.

These events were not easy for Jan and Els’ sons either.

The day before the euthanasia appointment, Jan, Els, their son and grandson spent time together.

Jan told his son about the caravan’s peculiar features and gave him some advice on how to make it ready for sale.

His sons described that day in the following words:

“We went for a walk on the beach with my mom. The kids played games, jokes were made. It was a very strange day. That evening at dinner, I had tears in my eyes as I watched us eat together for the last time.”

On the day of the appointment, not only Jan and Els’ sons and daughters-in-law, but also the couple’s closest friends and siblings gathered at the nursing home.

They talked about their memories for two hours until their doctors arrived.

For Jan, they played the Beatles’ Now and Then; for Els, they played Travis’ Idlewild.

“The last half hour was very difficult for us. The doctors came and everything happened at once,” their son recounted.

Els van Leeningen and Jan Faber died together on Monday, June 3, 2024, as a result of lethal drugs prescribed by doctors.

Their son has not yet put his caravan up for sale; he decided to go on holiday with his wife and children in this caravan:

“Of course, one day I will sell the caravan. First, I want to make memories here with my family.”